The UK government has confirmed it will move forward on a major ex ante competition reform aimed at Big Tech, as it set out its priorities for the new parliamentary session earlier today.

However it has only said that draft legislation will be published over this period — booting the prospect of passing updated competition rules for digital giants further down the road.

At the same time today it confirmed that a “data reform bill” will be introduced in the current parliamentary session.

This follows a consultation it kicked off last year to look at how the UK might diverge from EU law in this area, post-Brexit, by making changes to domestic data protection rules.

There has been concern that the government is planning to water down citizens’ data protections. Details the government published today, setting out some broad-brush aims for the reform, don’t offer a clear picture either way — suggesting we’ll have to wait to see the draft bill itself in the coming months.

Read on for an analysis of what we know about the UK’s policy plans in these two key areas…

Ex ante competition reform

The government has been teasing a major competition reform since the end of 2020 — putting further meat on the bones of the plan last month, when it detailed a bundle of incoming consumer protection and competition reforms.

But today, in a speech setting out prime minister Boris Johnson’s legislative plans for the new session at the state opening of parliament, it committed to publish measures to “create new competition rules for digital markets and the largest digital firms”; also saying it would publish “draft” legislation to “promote competition, strengthen consumer rights and protect households and businesses”.

In briefing notes to journalists published after the speech, the government said the largest and most powerful platform will face “legally enforceable rules and obligations to ensure they cannot abuse their dominant positions at the expense of consumers and other businesses”.

A new Big Tech regulator will also be empowered to “proactively address the root causes of competition issues in digital markets” via “interventions to inject competition into the market, including obligations on tech firms to report new mergers and give consumers more choice and control over their data”, it also said.

However another key detail from the speech specifies that the forthcoming Digital Markets, Competition and Consumer Bill will only be put out in “draft” form over the parliament — meaning the reform won’t be speeding onto the statue books.

Instead, up to a year could be added to the timeframe for passing laws to empower the Digital Markets Unit (DMU) — assuming ofc Johnson’s government survives that long. The DMU was set up in shadow form last year but does not yet have legislative power to make the planned “pro-competition” interventions which policymakers intend to correct structural abuses by Big Tech.

(The government’s Online Safety Bill, for example — which was published in draft form in May 2021 — wasn’t introduced to parliament until March 2022; and remains at the committee stage of the scrutiny process, with likely many more months before final agreement is reached and the law passed. That bill was included in the 2022 Queen’s Speech so the government’s intent continues to be to pass the wide-ranging content moderation legislation during this parliamentary session.)

The delay to introducing the competition reform means the government has cemented a position lagging the European Union — which reached political agreement on its own ex ante competition reform in March. The EU’s Digital Markets Act is slated to enter into force next Spring, by which time the UK may not even have a draft bill on the table yet. (While Germany passed an update to its competition law last year and has already designated Google and Meta as in scope of the ex ante rules.)

The UK’s delay will be welcomed by tech giants, of course, as it provides another parliamentary cycle to lobby against an ex ante reboot that’s intended to address competition and consumer harms in digital markets which are linked to giants with so-called “Strategic Market Status”.

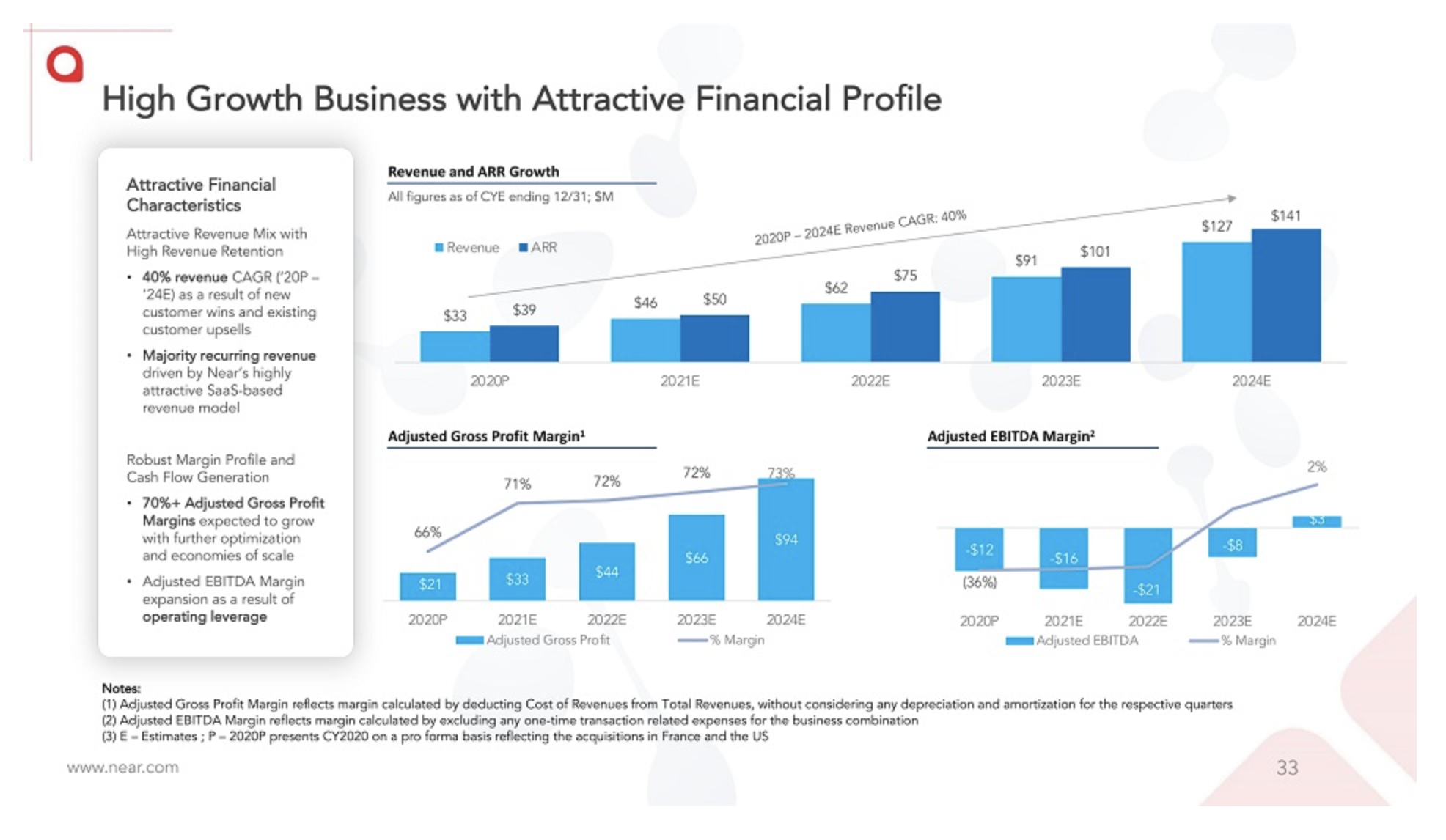

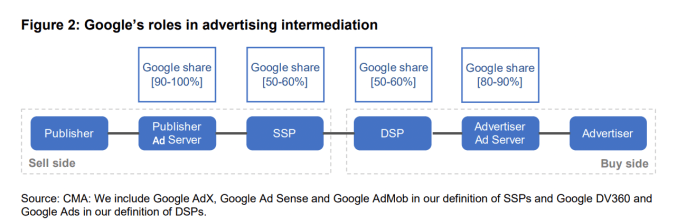

This includes issues that the UK’s antitrust regulator, the CMA, has already investigated and confirmed (such as Google and Facebook’s anti-competitive dominance of online advertising); and others it suspects of harming consumers and hampering competition too (like Apple and Google’s chokepoint hold over their mobile app stores).

Any action in the UK to address those market imbalances doesn’t now look likely before 2024 — or even later.

Recent press reports, meanwhile, have suggested Johnson may be going cold on the ex ante regime — which will surely encourage Big Tech’s UK lobbyists to seize the opportunity to spread self-interested FUD in a bid to totally derail the plan.

The delay also means tech giants will have longer to argue against the UK introducing an Australian-style news bargaining code — which the government appears to be considering for inclusion in the future regime.

One of the main benefits of the bill is listed as [emphasis ours]:

“Ensuring that businesses across the economy that rely on very powerful tech firms, including the news publishing sector, are treated fairly and can succeed without having to comply with unfair terms.”

“The independent Cairncross Review in 2019 identified an imbalance of bargaining power between news publishers and digital platforms,” the government also writes in its briefing note, citing a Competition and Markets Authority finding that “publishers see Google and Facebook as ‘must have’ partners as they provide almost 40 per cent of large publishers’ traffic”.

Major consumer protection reforms which are planned in parallel with the ex ante regime — including letting the CMA decide for itself when UK consumer law has been broken and fine violating platforms over issues like fake reviews, rather than having to take the slow route of litigating through the courts — are also on ice until the bill gets passed. So major ecommerce and marketplace platforms will also have longer to avoid hard-hitting regulatory action for failures to purge bogus reviews from their UK sites.

Consumer rights group, Which?, welcomed the government’s commitment to legislate to strengthen the UK’s competition regime and beef up powers to clamp down on tech firms that breach consumer law. However it described it as “disappointing” that it will only publish a draft bill in this parliamentary session.

“The government must urgently prioritise the progress of this draft Bill so as to bring forward a full Bill to enact these vital changes as soon as possible,” added Rocio Concha, Which? director of policy and advocacy, in a statement.

Data reform bill

In another major post-Brexit policy move, the government has been loudly flirting with ripping up protections for citizens’ data — or, at least, killing off cookie banners.

Today it confirmed it will move forward with ‘reforming’ the rules wrapping people’s data — just without being clear about the exact changes it plans to make. So where exactly the UK is headed on data protection still isn’t clear.

That said, in briefing notes on the forthcoming data reform bill, the government appears to be directing most focus at accelerating public sector data sharing instead of suggesting it will pass amendments that pave the way for unfettered commercial data-mining of web users.

Indeed, it claims that ensuring people’s personal data “is protected to a gold standard” is a core plank of the reform.

A section on the “main benefits” of the reform also notably lingers on public sector gains — with the government writing that it will be “making sure that data can be used to empower citizens and improve their lives, via more effective delivery of public healthcare, security, and government services”.

But of course the devil will be in the detail of the legislation presented in the coming months.

Here’s what else the government lists as the “main elements” of the upcoming data reform bill:

- Using data and reforming regulations to improve the everyday lives of people in the UK, for example, by enabling data to be shared more efficiently between public bodies, so that delivery of services can be improved for people.

- Designing a more flexible, outcomes-focused approach to data protection that helps create a culture of data protection, rather than “tick box” exercises.

Discussing other “main benefits” for the reform, the government touts increased “competitiveness and efficiencies” for businesses, via a suggested reduction in compliance burdens (such as “by creating a data protection framework that is focused on privacy outcomes rather than box-ticking”); a “clearer regulatory environment for personal data use” which it suggests will “fuel responsible innovation and drive scientific progress”; “simplifying the rules around research to cement the UK’s position as a science and technology superpower”, as it couches it; and ensuring the data protection regulator (the ICO) takes “appropriate action against organisations who breach data rights and that citizens have greater clarity on their rights”.

The upshot of all these muscular-sounding claims boils down to whatever the government means by an “outcomes-focused” approach to data protection vs “tick-box” privacy compliance. (As well as what “responsible innovation” might imply.)

It’s also worth mulling what the government means when it says it wants the ICO to take “appropriate” action against breaches of data rights. Given the UK regulator has been heavily criticized for inaction in key areas like adtech you could interpret that as the government intending the regulator to take more enforcement over privacy breaches, not less.

(And its briefing note does list “modernizing” the ICO, as a “purpose” for the reform — in order to “[make] sure it has the capabilities and powers to take stronger action against organisations who breach data rules while requiring it to be more accountable to Parliament and the public”.)

However, on the flip side, if the government really intends to water down Brits’ privacy rights — by say, letting businesses overrule the need to obtain consent to mine people’s info via a more expansive legitimate interest regime for commercial entities to do what they like with data (something the government has been considering in the consultation) — then the question is how that would square with a top-line claim for the reform ensuing “UK citizens’ personal data is protected to a gold standard”?

The overarching question here is whose “gold standard” the UK is intending to meet? Brexiters might scream for their own yellow streak — but the reality is there are wider forces at play once you’re talking about data exports.

Despite Johnson’s government’s fondness for ‘Brexit freedom’ rhetoric, when it comes to data protection law the UK’s hands are tied by the need to continue meeting the EU’s privacy standards, which require the an equivalent level of protection for citizens’ data outside the bloc — at least if the UK wants data to be able to flow freely into the country from the bloc’s ~447M citizens, i.e. to all those UK businesses keen to sell digital services to Europeans.

This free flow of data is governed by a so-called adequacy decision which the European Commission granted the UK in June last year, essentially on account that no changes had (yet) been made to UK law since it adopted the bloc’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018 by incorporating it into UK law.

And the Commission simultaneously warned that any attempt by the UK to weaken domestic data protection rules — and thereby degrade fundamental protections for EU citizens’ data exported to the UK — would risk an intervention. Put simply, that means the EU could revoke adequacy — requiring all EU-UK data flows to be assessed for legality on a case-by-case basis, vastly ramping up compliance costs for UK businesses wanting to import EU data.

Last year’s adequacy agreement also came with a baked in sunset clause of four years — meaning it will be up for automatic review in 2025. Ergo, the amount of wiggle room the UK government has here is highly limited. Unless it’s truly intent on digging ever deeper into the lunatic sinkhole of Brexit by gutting this substantial and actually expanding sunlit upland of the economy (digital services).

The cost — in pure compliance terms — of the UK losing EU adequacy has been estimated at between £1BN-£1.6BN. But the true cost in lost business/less scaling would likely be far higher.

The government’s briefing note on its legislative program itself notes that the UK’s data market represented around 4% of GDP in 2020; also pointing out that data-enabled trade makes up the largest part of international services trade (accounting for exports of £234BN in 2019).

It’s also notable that Johnson’s government has never set out a clear economic case for tearing up UK data protection rules.

The briefing note continues to gloss over that rather salient detail — saying that analysis by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) “indicates our reforms will create over £1BN in business savings over ten years by reducing burdens on businesses of all sizes”; but without specifying exactly what regulatory changes it’s attaching those theoretical savings to.

And that’s important because — keep in mind — if the touted compliance savings are created by shrinking citizens’ data protections that risks the UK’s adequacy status with the EU — which, if lost, would swiftly lead to at least £1BN in increased compliance costs around EU-UK data flows… thereby wiping out the claimed “business savings” from ‘less privacy red tape’.

The government does cite a 2018 economic analysis by DCMS and a tech consultancy, called Ctrl-Shift, which it says estimated that the “productivity and competition benefits enabled by safe and efficient data flows would create a £27.8BN uplift in UK GDP”. But the keywords in that sentence are “safe and efficient”; whereas unsafe EU-UK data flows would face being slowed and/or suspended — at great cost to UK GDP…

The whole “data reform bill” bid does risk feeling like a bad-faith PR exercise by Johnson’s thick-on-spin, thin-on-substance government — i.e. to try to claim a Brexit ‘boon’ where there is, in fact, none.

See also this “key fact” which accompanies the government’s spiel on the reform — claiming:

“The UK General Data Protection Regulation and Data Protection Act 2018 are highly complex and prescriptive pieces of legislation. They encourage excessive paperwork, and create burdens on businesses with little benefit to citizens. Because we have left the EU, we now have the opportunity to reform the data protection framework. This Bill will reduce burdens on businesses as well as provide clarity to researchers on how best to use personal data.”

Firstly, the UK chose to enact those pieces of legislation after the 2016 Brexit vote to leave the EU. Indeed, it was a Conservative government (not led by Johnson at that time) that passed these “highly complex and prescriptive pieces of legislation”.

Moreover, back in 2017, the former digital secretary Matt Hancock described the EU GDPR as a “decent piece of legislation” — suggesting then that the UK would, essentially, end up continuing to mirror EU rules in this area because it’s in its interests to do so to in order to keep data flowing.

Fast forward five years and the Brexit bombast may have cranked up to Johnsonian levels of absurdity but the underlying necessity for the government to “maintain unhindered data flows”, as Hancock put it, hasn’t gone anywhere — or, well, assuming ministers haven’t abandoned the idea of actually trying to grow the economy.

But there again the government lists creating a “pro-growth” (and “trusted”) data protection framework as a key “purpose” for the data reform bill — one which it claims can both reduce “burdens” for businesses and “boosts the economy”. It just can’t tell you how it’ll pull that Brexit bunny out of the hat yet.

🫥

🫥