GWI, a UK-based tech company — formerly GlobalWebIndex — that’s built up a SaaS business which disrupts traditional offline market research methods with a global network of data contributors, mobile surveys and a self-serve platform for surfacing rich consumer insights to customers that include tech giants like Google, has closed a $180 million Series B at a valuation of more than $850M.

The growth funding round is led by global investment firm Permira — and is only GWI’s second tranche of VC after a $40M Series A back in 2018.

The 2009-founded startup was bootstrapped for years by founder and CEO, Tom Smith, before finally taking external investment a few years ago with the goal of scaling access to its consumer lifestyle and habits data beyond dedicated research teams — to “non expert” professionals who may be working in all sorts of roles right across a business.

“That huge market opportunity needed us to really scale up both the GTM [go-to-market] teams but also engineering teams, build up bigger data sets — that’s what we started to really push the peddle on in 2018. And that was a great success, in terms of scaling up the business. That’s really why we’ve come back now to do a growth round because that market opportunity has got bigger,” Smith tells TechCrunch.

Following its $40M Series A, GWI says it’s tripled recurring revenue and grown to nearly 400 employees based across offices in London, New York, Prague, and Athens. Last year it also opened an office in Singapore.

“It’s a really large market, it’s very global,” he adds on why the company has gone back for a second dip into VC now. “The more capital we have to expand out GTM, data-sets and build world class user interface solutions the quicker we’ll be able to build that traction in the global market.”

Rising competition from ‘no code’ touting research-as-a-service rivals (such as London-based Attest) is also likely giving GWI cause to step on the growth gas.

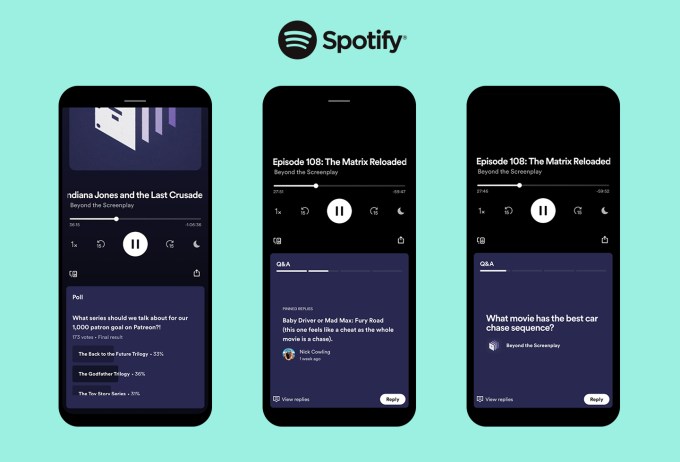

Smith’s original itch to transform traditional (offline) market research methods — infamous for being slow and costly — led to GWI building out a platform for large scale, high frequency data collection which can serve up instantaneous audience profiling and consumer insights to a roster of customers that includes giants like Facebook and Google (who are hardly short of a bit of personal data themselves). Other customers GWI names include Spotify, Twitter, EA, Red Bull, WPP, and Omnicom.

It says it has around 700 customers at this stage.

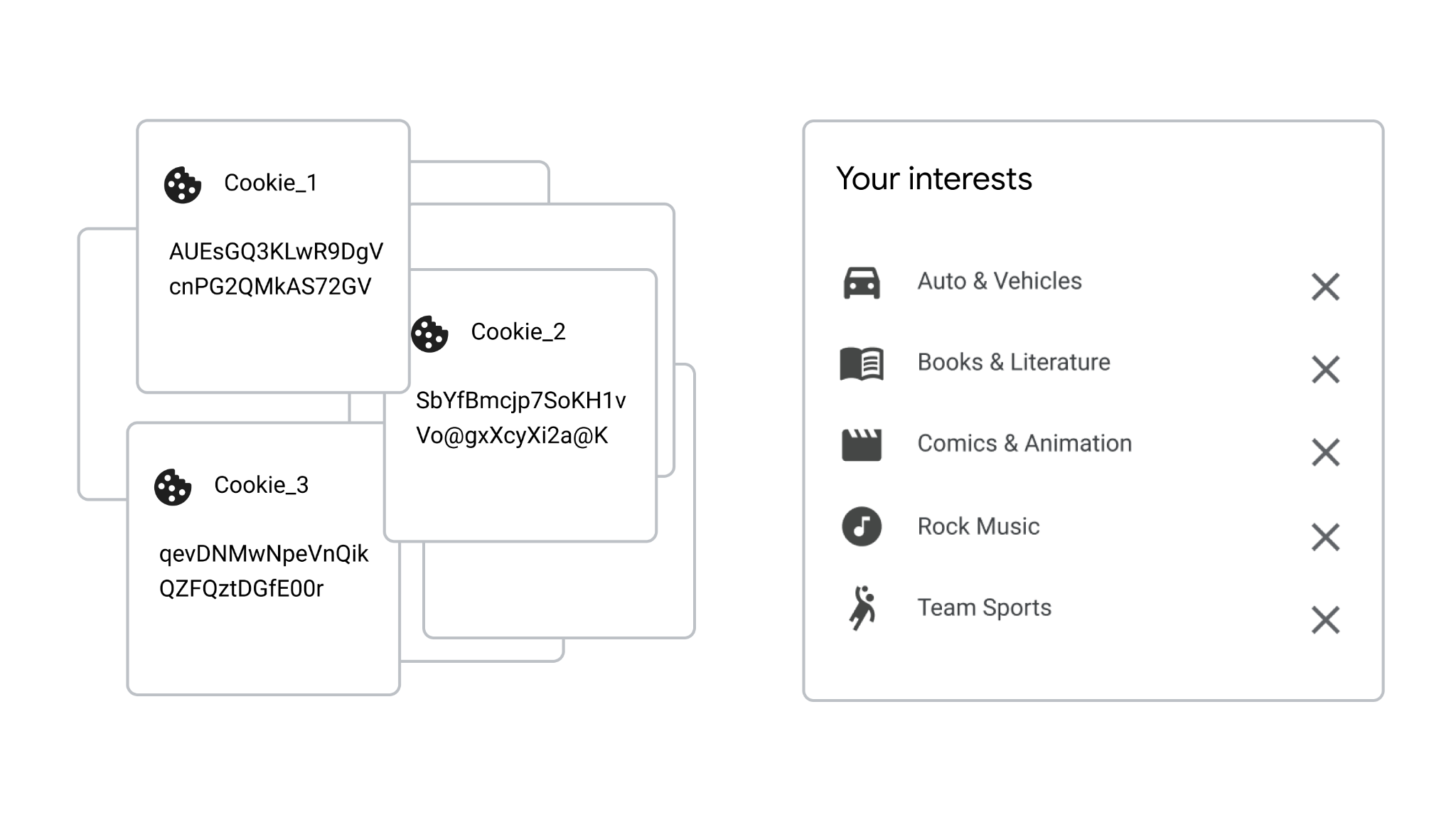

“The kind of customers we work with now are very large technology companies and platforms who essentially have all the first party data you can think of but they don’t have the richness of that data — they need independent, rich, profiling data to build a better understanding of customer subsets, and that’s what we provide.”

“The big area of growth for us is enrichment of first party data,” Smith adds. “This is where we match — probabilistically, through similar types of demographics and variables (or in some cases deterministically between IDs) — and in an anoymized way we’re able to enrich their first party data and provide our profiling data.”

GWI’s market research platform is fed by around 22 million “digitally connected” consumers across (currently) 48 countries, who take detailed surveys (meaning there’s opt in consent to use of their data) via third party panel providers which plug into GWI’s platform to continuously supply that core data.

It then does its own weighting and probabilistic matching to extrapolate out from the millions of (pseudonymized) survey responses it receives — to what it describes as “global insights at scale, representing the views of 2.7BN, digitally-connected consumers”; covering data about consumers’ demographics, preferences, and behavioural attitudes — all with the goal of helping customers (major brands, agencies, and media organisations) gain a deeper understanding of their audiences.

“We’re looking at preference, attitudes, lifestyles, brand choices, types of media consumed, demographics — the broad subsets,” says Smith, sketching the broad-brush insights the platform serves up to help customers profile their audiences.

Any direct identifiers are stripped out of the survey response data prior to GWI getting it, per Smith — replaced with a unique ID so it’s still possible for its customers to ask follow up questions via the platform without the individuals needing to be identified to customers or to GWI. So the pitch is ‘privacy safe’ behavioral profiling data at scale.

“What we’re doing really differently — it hasn’t been done before — is that we’ve applied technology to the process of [market research] data collection. So we’re running an incredibly large scale data collection, highly frequent in terms of collection process, delivery to customers and all of that is made available inside a self-service platform… instantaneously accessible. Which is a very unique proposition.”

“Every company needs to understand their target audiences, whether they’re future customers, current customers, or the market place they operate in. And increasingly, as companies move — thanks to the digital world we live in — the possibility to engage and reach customers from anywhere in the world is a very real possibility,” he adds.

“But the challenges of understanding those audiences become massively complicated. And if you use market research — which is what people have done traditionally it’s going to take you months, cost millions of dollars. And you going to end up with a very substandard set of data, ultimately.

“The problem we’re solving is by collecting this massive pool of global data any company, regardless of size, scale or budget, can utilize our data to build a really rich understanding of their target audiences that would be impossible with market research.”

Smith says GWI’s latest chunk of VC funding will go on further expansion of GWI’s geographical reach and demographic depth. Or, put more simply, it’s going to capture more data-points from more consumers in more countries.

“This will enable us to provide instant answers to any question and to better understand people,” he says, adding: “We will represent more communities, particularly in underserved markets and segments than any data set before.

“We currently cover 48 countries, but this will increase to 50 in the coming months, and we’ll be expanding that further and adding more data sets across a range of audiences and verticals. We already cover over 40,000 attributes and over 4,000 brands.”

Another big focus for the funding is on the UX of the platform — with Smith saying they want to make it “even more accessible”.

“We want anyone, regardless of research experience, to be able to answer questions, develop meaningful insights and drive decisions in their day-to-day workflows. Creating insights should be as easy as searching Google; and sharing them and aligning across an organisation should be effortless and embedded whether the company is five people or five million.

“This means major investment in consumer grade UX, machine learning for insights automation, and natural language processing.”

“Most businesses are well aware of the need for a deep understanding of their audiences, but for many, this is still a one-off piece of research undertaken every year,” he adds.

“Market research as an industry has stubbornly refused to evolve, clinging on to high-cost service based models, offline methods, and a lack of scale. We are demystifying audience insight and democratising the data to make global audience insight a reality for any business of any size, without the need for deep research expertise or extensive training.”

While he confirms that a small percentage (1%) of GWI’s customers do also use tracking cookies (and/or pixels) in conjunction with the audience insights its platform surfaces, he’s not concerned about the imminent demise of third party cookies.

In recent years, Google has signalled an intent to deprecate support for tracking technologies in Chrome — via its evolving Privacy Sandbox suite of proposed alternative ad targeting technologies. Other browsers already block third party cookies by default. So the direction of travel of for core web infrastructure is toward a cookie-less future. Which may end up making alternative sources of consumer insight data more valuable.

“GWI’s survey-led data does not rely on cookies to provide audience insights to our customers,” says Smith, adding: “We’re actually excited about the prospect of a cookieless future. It presents so many opportunities for the industry to rethink how it uses behavioural data.

“At GWI we believe strongly that data insights are so much more valuable when they’re based on (or fused with) zero-party data. We know that there are organisations everywhere scrambling to find alternatives to the cookie, many of which appear to be very cookie-esque in nature. Which is probably just kicking the can down the road.

“For GWI, we are focused on proving that probabilistic matching, using really great zero-party data, can be far more effective.”

What does he mean exactly by “zero party data”? Smith says this refers to information that’s been “totally anonymized and can never be linked back to an individual but can be used to drive additional profiling or probabilistic matching”.

“There’s really no way you can tie it back to an individual because of the nature of the data that our customers want us to collect — which is attitudes, lifestyles, outlooks. It’s all the stuff that you can’t collect through behavioral data [i.e. such as tracking cookies] really. You just can’t tie it back to one individual person,” he argues, discussing the robustness of the anonymity.

In theory, if a customer of GWI were to have enough of its own extremely high dimension first party data — on millions or even billions of global consumers (as, for example, Facebook has) — there might, potentially, be a way for a customer to reverse the pseudonymity if they could link individual survey takers to identifiable user accounts on other service/s based on matching/mapping profiled interests.

However as GWI’s platform provides access to aggregated as well as anonymized data it’s indeed hard to see how that could happen. (At least outside of a custom integration that did not aggregate the data or else substantially reduced the level of aggregation and enabled matching with other data-sets.)

“They don’t use our data in this way,” Smiths says of Facebook own use of GWI’s service. “They would use it completely independently to their first party data. They are analyzing our data-sets to provide independent profiling data of their audiences in different countries — and they just work with GWI data in silo. You look at data on an aggregated basis. You look at segments of Facebook users, how likely that they are to engage with specific brands or exhibit specific behaviors — there’s absolutely no linkage to first party data.”

“That’s what 99% of our customers use-cases are — they’re using our data in silo to build insights around audiences which they then translate and use elsewhere,” he adds.

Smith also confirms that the unique IDs GWI receives from panel providers (which would likely still constitute personal data under EU law) are never passed to customers.

“The general movement from GDPR and towards individual privacy has been really good for us because people increasingly having to work with aggregated and anonymized data — which is what is our absolute strength and really core for our proposition,” he adds.

“I started the business in 2009 which was the last really great recession. Obviously we’re going through interesting times now but it’s a very different dynamic to back then. That was a tough environment to build a business. There was no way I was going to raise early stage investment for the idea I brought to market — and also it was a research-based solution, which was very much seen as probably not the future of audience insights.”

Over a decade on from the spark of an idea Smith had, with use of behavioral data facing a rising tide of privacy concern and regulatory control, his bet on modernizing the business of market research — via big data, aggregation and probabilistic modelling — looks well positioned to cater to changing compliance requirements while still being able to serve businesses with valuable consumer insights.

Provided GWI can iterate and evolve its UX fast enough to keep up with ‘no code’ touting rivals that are fast following ballooning demand for research-as-a-service.

“What we’re seeing a demand for is a shift from deterministic data — so ‘I can target this individual’ — to one where it’s probabilistic,” says Smith on changing customer demand. “So… based on data we can see or the attributes we can see through the first party data within the browser, they’re likely to fit this bucket in terms of attitudes and lifestyles. And that probabilistic matching is far easier to make happen — and to do at real scale [which] is what you need for advertising to be effective. And we’re increasingly getting asked to probabilistically match our data.

“The other interesting thing for us is that as more and more media runs through it’s basically being bought on first party deterministic data — directly from Facebook or all the big vendors of advertising space — [and] they’ll use our data to perform the key parts of that strategic planning process: Who is my audience, what do they look like? They’ll build that rich profiling and then take the insights from the audience and just translate those into a platform that has first party or deterministic data.

“They’re not directly matching it but they’re taking the insights to inform the types of audiences they should reach through Facebook or Google or Snap or Twitter or TikTok. The people that own the data directly. You don’t actually need to deterministically match that data — and that’s something that’s really in demand.”

Smith adds that GWI is in the process of rolling out a new feature that will enable customers to push an audience that’s been identified in its platform into Facebook — based on “matching the common variables” — much like Facebook’s own ‘lookalike audience’ ad targeting tool.

“There’s no direct data link but you’re taking commonalities and those commonalities drive your media buy and the audiences you should reach for in Facebook,” says Smith, adding: “And that’s really where the industry is moving in my opinion.

“You’re modelling out probabilistic likelihood that that audience fits the audience you want — and actually more valuable is the insights you derive about who your audience is, they really determine where you should activate your media plan.”

Commenting on GWI’s Series B in a statement, Alex Melamud, principal at Permira, said: “Understanding the digital consumer will continue to be increasingly important to brands, agencies, and media organisations who focus on engaging and acquiring customers through digital channels. Companies competing in today’s marketplace need instant audience insights and we believe GWI’s modern platform and globally, harmonised data set provides a unique solution to any data storyteller. We look forward to leveraging our global platform to support GWI’s continued growth and expansion across international markets.”

In another supporting statement, Ron Shah, partner at New York-based VC Stripes, who led its Series A, added: “GWI’s exceptional products should be in the hands of every professional who wants to better understand their customers and make smarter, data-driven decisions, and this milestone is a powerful step forward for the company. Since our original investment in 2018, Tom and the GWI team have made great strides in delivering a transformative and superior product and we believe they’re just getting started. We’re thrilled to have Permira join us in this journey to make GWI’s ambitions a reality.”

Don’t bootstrap for too long

With GWI trotting along a path that could lead to a unicorn valuation this once bootstrapped startup has come a long way — in time and money — from earlier years, such as when Smith had to take some 200 meetings to nail down its first customer (Microsoft). Evidently there’s been a fair amount of sweat and pain involved in scaling this particular SaaS business. So what tips does Smith have for other bootstrapping founders?

“There are many more avenues for raising capital now. Alternative finance just didn’t exist back then,” he notes, perhaps a little ruefully. “There are some obvious things — you have to keep the business extremely lean. The product at the beginning was fairly rudimentary but it solved one problem for customers which was how to understand their audience on a global basis. Solve that on a small scale.

“You’ve got to try and keep it very focused, very lean — and just try and solve one small problem. Most of what we did in the very early days was more service based. There wasn’t really any technology. We tried to minimize the costs. I was a non-technical founder so that didn’t help. But try and fulfil it as a service to begin with — before you really invest in engineering technology which is obviously very hard to pull off and very expensive.

“You [also] need to consider what product you’re selling. Ultimately we’re selling market research which is a high value product that people will pay a good high ticket for and were used to paying for at the beginning of a payment cycle up front. Not all products would suit that. So you need to understand the dynamics of what you’re selling and if it would suit that model. It worked for us — but it’ll only get you so far. At some point if you’re really going to scale you’ve got to spend more than you’re bringing through the door, basically.”

“I probably wouldn’t have bootstrapped for quite as long as I did,” Smith adds. “Try to get to a position of funding earlier.”