Google has responded to allegations contained in a recently unsealed US antitrust lawsuit that it worked covertly to stall European Union privacy legislation that could have blasted a huge hole in its behaviorial advertising business.

Per the US states’ suit, a couple of years after a European Commission proposal to update the EU’s ePrivacy Directive — to replace it with a more widely applicable Regulation — the tech giant was privately celebrating what it described as a “successful” tilt at “slowing down and delaying” the privacy legislation.

The update to the EU’s privacy rules around people’s electronics communications (and plenty more besides) remains stalled even now, with negotiations technically ‘continuing’ — just without any agreement in sight. So Google’s ‘success’ looks overwhelming.

That said, the adtech giant can’t take all the credit: The US states’ case against Google quotes an internal memo from July 2019 — in which it claims to have been “working behind the scenes hand in hand” with the other four of the ‘big five’ tech giants (GAFAM) to forestall consumer privacy efforts.

Here’s the relevant allegation from the antitrust case against Google:

“(b) Google secretly met with competitors to discuss competition and forestall consumer privacy efforts. The manner in which Google has actively worked with Big Tech competitors to undermine users’ privacy further illustrates Google’s pretextual privacy concerns. For example, in a closed-door meeting on August 6, 2019 between the five Big Tech companies—including Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft—Google discussed forestalling consumer privacy efforts. In a July 31, 2019 document prepared in advance of the meeting, Google memorialized: “we have been successful in slowing down and delaying the [ePrivacy Regulation] process and have been working behind the scenes hand in hand with the other companies.””

As well as putting questions to Google, TechCrunch contacted Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft about the August 6 meeting referenced in Google’s memo.

A spokeswomen for Microsoft declined comment — saying only: “We have nothing to share.”

Amazon and Facebook did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

However last December Politico reported on an internal Amazon document, dating from 2017, which showed the ecommerce giant making an eerily similar boast about eroding support for the ePrivacy Regulation.

“Our campaign has ensured that the ePrivacy proposal will not get broad support in the European Parliament,” Politico reported Amazon writing in the document. “Our aim is to weaken the Parliament’s negotiation position with the Council, which is more sympathetic to industry concerns,” the text went on.

According to its report, Amazon’s lobbying against ePrivacy focused on pushing the Parliament for “less restrictive wording on affirmative consent and pushing for the introduction of legitimate interest and pseudonymization in the text” — which, as the news outlet observes, are legal grounds that would give companies greater scope to collect and use people’s data.

Amazon’s motivation for wanting to degrade the level of privacy protections wrapping Europeans’ data is clear when you consider the $42M fine it was slapped with last year by a single EU data protection watchdog (France’s CNIL) under current ePrivacy laws. Its infringement? Dropping tracking cookies without consent.

Amazon’s digital advertising business isn’t as massive as Google’s (although it is growing). But the ecommerce behemoth has plenty of incentive to track and profile Internet users — not least for targeting them with stuff for sale on its ‘everything store’.

A beefed up ePrivacy could put limits on such tracking. And evidently Amazon would prefer that it didn’t have to ask your permission for its algorithms to figure out how to get you to buy more stuff on Amazon.fr or .de or .es and so on.

But what about Apple? It’s certainly unusual in the list as a (rare) tech giant that’s built a reputation as a champion of user privacy.

Indeed, back in 2018, Apple’s CEO personally stood in Brussels lauding EU privacy laws and calling for the region’s lawmakers to go further in reining in the ‘data industrial complex‘, as Tim Cook dubbed the dominant strain of adtech at the time. So seeing Apple’s name in an anti-privacy lobbying list is certainly surprising.

Asked about Google’s memo, Apple did at least response: It told us that no Apple representative was present at the August 6, 2019 meeting.

However it did not provide a broader public statement distancing itself from Google’s claim of joint work to forestall consumer privacy efforts. So Apple’s limited rebuttal leaves plenty of questions about the aligned interests of tech giants when it comes to processing people’s data.

Zooming out, the ruinous damage to people’s privacy* which flows from the dominance of a handful of overly powerful Internet giants has been a slowly emerging thread in antitrust cases against big tech. (See for example: The German FCO’s pioneering litigation against Facebook’s superprofiling which Europe’s top court is set to weigh in on.)

Unfortunately, competition regulators have generally been slow to recognize privacy abuse as a key lever for Internet giants to unfairly lock in market dominance. Although the penny does finally seem to be dropping.

Just last week, a report by Australia’s ACCC highlighted how alternative search business models, which don’t rely on tracking people, are being held back by Google’s competitive lock on the market — and, crucially, by its grip on people’s data.

Effective remedies for breaking big tech’s hold over consumers and competition, alike, will therefore require public authorities to grasp the key role privacy plays in protecting people and markets.

*not to mention the other human rights that privacy helps protect…

Mind the ePrivacy gap

The EU’s proposed update to ePrivacy is aimed at extending the scope of existing rules attached to the privacy of electronic communications so that they cover, among other things, comms and metadata that’s travelling over Internet platforms; not just message data that telcos carry on their mobile networks.

That change would put plenty of big tech platforms and products in the frame. Google’s Gmail, for example.

And it’s interesting to note that, later in the same year the ePrivacy proposal was presented, Google announced it would stop scanning Gmail message data for ads.

But of course Google hasn’t stopped tracking user activity across the lion’s share of its products or the majority of the mainstream web, via data-harvesting tools like Google Analytics, Maps, YouTube embeds and so on.

Rules that cover how Internet users can be tracked and profiled for behavioral ads are also in scope in the Commission’s ePrivacy Regulation proposal. And that could present a far more existential threat to an adtech giant like Google — which makes almost all its money by tracking and profiling Internet users’ via their digital activity (and other data sources), to calculate how best to sell their attention to advertisers.

Another consumer friendly goal for the ePrivacy proposal is to simplify the EU’s much hated cookie consent rules — potentially by reviving a ‘Do Not Track’ style mechanism where consent could be pre-defined ahead of time and signalled automatically via the browser, doing away with loads of annoying pop-ups.

So blocking progress on that front has basically consigned Europeans to years of tedious clicking which — all too often — still leaves people with no real choice over how their data is used, given how widely the EU’s consent rules are flouted by adtech.

There’s other stuff in the ePrivacy proposal too. EU lawmakers want the update to cover machine-to-machine comms — to regulate privacy around the still nascent but rapidly expanding connected devices space (aka, IoT or the Internet of Things), in order to keep pace with the rise of smart home technologies — which offer new and intimate avenues for undermining privacy.

The scope of the regulation does, therefore, touch other industries beyond pure adtech. And it’s true that big tech hasn’t been alone in opposing ePrivacy. (Big telco has also lobbied fiercely against it too, for example, basically in the hopes of getting the same free license over data as big adtech.)

But a 2018 report by the NGO, Corporate Lobby Europe, which tracks regional lobbying, fingered digital publishers and the digital advertising lobby as the biggest guns ranged against ePrivacy — pointing to frequent collaboration between them (“As print media circulations fall, online advertising has become increasingly important to publishers”).

This collaboration saw publishers stepping up “fear-mongering” hyperbole against ePrivacy — claiming it would mean the ‘end of the free press’.

There was no nuance in this narrative. No recognition that other forms of (non-tracking) advertising are available. And no air time for the salient point that if tracking ads were not the dysfunctional ‘norm’, publishers could recover the value of their own audiences — rather than having them arbitraged by platform giants like Google (now facing antitrust litigation on both sides of the Atlantic for how it operates its adtech) and the adtech middlemen enabled by this opaque model. Publishers have essentially been used as a table for others to feast and left with the scraps.

But the problem is big (ad)tech’s influence extends to selling the notion of market dominance via a business model that views people as attention nodes to be data-mined and manipulated for profit.

This means it’s also ‘advertising’ tracking as a business model for other industries to follow — providing newly digitizing (or, in the case of publishers, revenue-challenged) industries with an incentive to lobby alongside it for lower consumer protections in the hopes of cutting a slice of a Google-sized pie.

Publishers’ ‘share’ of the digital ad pie is of course nowhere near Google-sized. Their ad revenues have in fact been declining for years, which has led to the rash of paywalls now gating previously free content as scores switch to subscription models. (So so much for big adtech’s other cynically self-serving claim that the data-mining of Internet users supports a ‘free and open’ web; not if it’s quality information and professional journalism you want vs any old bs clickbait…)

Beyond publishers, the data harvesting potential of ‘smart’ things — be it a connected car or an in-home smart meter or doorbell — means many traditionally mechanical products (like cars) are becoming Internet-connected and increasingly data-driven. And with that switch comes the question of how will these industries and companies treat user data?

Big adtech is ready with an answer: Luring others to conspire against privacy by adopting surveillance so they too can build lucrative ad targeting businesses of their own. (Or, well, plug into big adtech’s data-feeder systems to fuel its self-serving profit machine).

And since adtech giants like Google have faced almost no regulatory action in the EU over the privacy apocalypse of their mass surveillance, other industries that are just starting to fire up their own data businesses could almost be forgiven for thinking it’s okay to copy-paste an anti-privacy model. So where GAFAM lobbies, car makers, publishers and telcos are willing to follow — fondly believing they are following the money.

Fondly — because the aforementioned antitrust suits suggest big adtech’s collusion against privacy extends to anti-competitive measures that have actively prevented others from getting a fair spin of the dice/slice of the pie. (See, for example, the ‘Jedi Blue’ allegations of a secret deal between Google and Facebook to rig the ad market against publishers and in their own favor.)

So, well, others lobbying against privacy alongside big tech tech risk looking like GAFAM’s useful idiots.

But wait, isn’t the EU supposed to have comprehensive privacy legislation? How is any of this even possible in the first place?

While it’s true the EU was (wildly) successful in passing the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) — which updated long standing data protection rules when it came into application in May 2018, beefing up requirements around consent as a legal basis for processing people’s data (for example) and adding some much needed teeth — the regulation has nonetheless been hamstrung by the presence of an outdated ePrivacy Directive sitting alongside it.

The Internet advertising industry has been able to leverage this legislative mismatch to claim loopholes for its continued heist of people’s data for ads. (And, unsurprisingly, disputes over the legal basis under which people’s electronic comms and metadata can be used have been a key ePrivacy sticking point.)

But the forces ranged against the update have seen an even bigger prize than just stopping ePrivacy: They’re trying to force the bloc into reverse and rip out protections the GDPR so recently cemented.

In a particularly ironic recent development, cookie consent friction has been seized upon and spun by ministers in the UK as suggested justification for downgrading the UK’s level of data protection — as Boris Johnson’s Conservatives look at diverging from the GDPR, post-Brexit.

Yet it’s not ‘simplified’ rules that are needed to fix cookie consent; it’s enforcement against systematic rule-breakers that have been allowed to make a mockery of the law in order they they can keep profiting by ignoring everyone’s right to privacy.

The long and short of this is that the damage to consumers and civic society across Europe as a result of regulatory inaction on adtech — and because of Google’s ‘successful’ lobbying against ePrivacy — looks staggeringly high.

While GDPR enforcement on adtech has been largely stalled these past three+ years, thanks (in no small part) to big tech’s forum shopping, if there had been an updated ePrivacy Regulation sitting alongside GDPR — adding enhanced transparency and consent requirements — it could have blasted tracking-based business models right out of EU waters years ago.

“The lobbying in context of ePrivacy was definitely of majestic size,” says Dr Lukasz Olejnik, an independent privacy researcher and consultant based in the EU. “This was readily felt by policymakers. Concerning the scale, it was the Olympic Games in lobbying.”

Asked what he believes has been the impact within the EU of the delaying of ePrivacy, Olejnik says the lobbying has likely slowed down data protection enforcement across the bloc and made outcomes more patchy, as well as holding up progress on further adapting the bloc’s rulebook to account for newer tracking techniques.

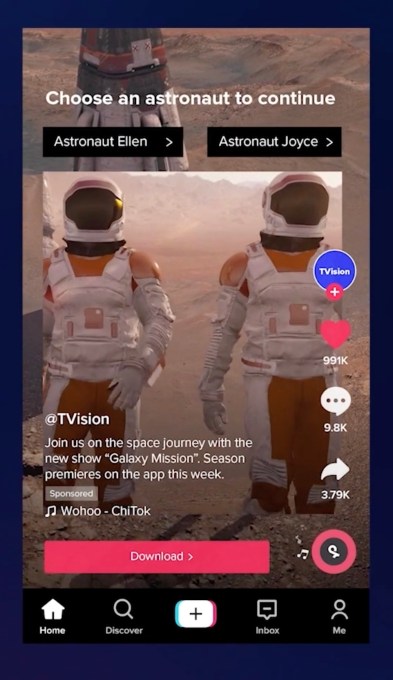

Or, to put it another way, the roadblock on ePrivacy has bought the adtech industry more time to get even further ahead of regulators — while simultaneously profiting off of its consentless exploitation of consumers’ data. (See for example, in the case of adtech giant Facebook, its shiny new placeholder about building “the Metaverse“, aka a new type of immersive, data-capturing infrastructure Facebook intends to stoke the fires of its ad engines into the far future under its new brand name ‘Meta’.)

“ePrivacy is currently not well aligned with GDPR. While in context of ePrivacy, all references to the previous Data Protection Directive are understood to be upgraded to GDPR, the current framework for protecting privacy in electronic communication is obsolete,” says Olejnik. “What is worse, some Member States still divide the data protection regulations, leaving enforcement of ePrivacy Directive to other, non-DPA [data protection agency] regulators. This means that one regulator is dealing with GDPR, and another with ePrivacy.

“It’s as problem mainly because the old ePrivacy Directive is not well adapted to GDPR. Meanwhile, the old ePrivacy fails to account for new tracking and ad targeting methods, as well as phenomenons of microtargeting political content based on the processing of personal data.”

There are currently moves by a number of MEPs to push for adtech-related amendments to another legislative proposal — the Digital Services Act (DSA) — to try to tackle rampant adtech data abuse by outlawing behavioral advertising entirely (in favor of contextual ads that don’t require mass surveillance).

But Olejnik doesn’t see that as the ideal route to defeat surveillance-based advertising.

“It’s not a good idea to take the fight and ideas such as curbing of microtargeting to other unrelated regulations, such as the DSA, just because some actors were late to the process,” he argues. “It is much better to finalise ePrivacy as soon as possible, and then immediately start another process of updating.

“That’s how it should work from the point of view of EU law and regulation baking.”

The Council did finally adopt a negotiating position on ePrivacy earlier this year (February) during the Portuguese presidency — proposing a version of the text that, critics say, waters down protections for data and provides fresh loopholes for adtech to exploit.

That in turn could mean ePrivacy ends up creating legislative cover for surveillance-based business models — reversing the stronger protections earlier EU lawmakers had intended and further undermining the GDPR’s (already weak) application against adtech… In short, a disaster for fundamental rights.

Whereas, if the ePrivacy update had been passed at around the same time as the GDPR, Olejnik reckons it would have resulted in a more practically successful upgrade of EU data protection rules.

“There would be chances to synchronise the upgrade,” he suggests. “It would also avert the subsequent backlash due to ‘GDPR paranoia’, which instantly made everybody — including policymakers and the industry — ultra-careful and less happy about any changes in this domain. So the changes would be of a practical nature.

“It would also be simpler and more coherent to do compliance preparations to the two at the same time.”

The EU now has a whole suite of new and even more ambitious digital legislative proposals on its plate — some of which the Commission proposed at the end of last year — including the (aforementioned) DSA; and the (tech giant-targeting) Digital Markets Act (DMA); where it wants to legislate for ex ante powers to tackle so-called “gatekeeper” platforms in order to reboot competition in tipped digital markets.

And of course all this further stretches (limited) legislative resources, while EU lawmakers are still stuck trying to pass an already out-of-date ePrivacy update.

So when adtech giant Facebook’s chief spin doctor and former UK deputy PM, Nick Clegg, makes a big show of claiming regulators are simply too slow and bumbling to keep up with fast-paced technology innovators, it pays to remember how much resource tech giants spend on intentionally delaying external oversight and retarding regulation — including shelling out on a phalanx of in-house lawyers to maintain a pipeline of cynical appeals to delay any actual enforcement.

In Facebook’s case, this includes the claim that the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) moved ‘too quickly’ when it arrived at a preliminary decision on a complaint — despite the complaint itself being over seven years old at that point…

One EU diplomat, who we are not identifying because they were not authorized to speak on the record about the ePrivacy file, spoke plainly about its problems. “This has been going on for fucking ages,” the source told us. “Big tech is lobbying like crazy.

“Everybody says they’re lobbying like crazy. Of course they are trying to hold back these issues — like consent for cookies.”

“If you look at the Commission it has a team of around 40 people who deal with the DMA, just to work on that, but Google probably has, like, 300 lawyers already in Brussels — just to paint a picture there,” the EU source added.

Other Brussels chatter this person reported hearing included a recent incident in which Google had apparently briefed journalists that it doesn’t have a dominant market position in search engines — and said its lawyers were “able to prove it”.

Wild, if true. (NB: A Google search for its market share in Europe points to Statcounter data which pegs its share at 92.98% between September 2020 and 2021.)

Back in reality, the trilogue phase of the ePrivacy discussions has technically been ongoing for months, involving the Commission, the Parliament and the Council — with another legislative tug-of-war over the final shape of any text that would then need to be put to a vote.

Slovenia currently holds the rotating Council presidency, meaning it is steering the file and representing the other Members States in the talks.

We contacted the Slovenian representation to the EU to ask whether it has been lobbied by Google (or any other tech giants) on ePrivacy and to ask for minutes of any lobbyist meetings.

A spokesperson denied any meetings with Google — and flat denied the file had been held up by the Council.

“The file is not being blocked within the EU Council, on the contrary. The work is [being] very intense,” it said. “After the first political trilogue under the Portuguese presidency at end of May 2021, the Slovene Presidency held numerous and regular meetings with the European Parliament at the technical level to discuss open issues and prepare the file for the second political trilogue that is planned for November 18, 2021.”

“As for your question related to meetings behind closed doors with Google on ePrivacy in 2019, no such meetings took place,” the spokesperson said, adding: “The Slovene Presidency has put digital files on top of our priorities and this goes for ePrivacy as well. We are actively working and negotiating on the ePrivacy legislation in line with the mandate that was given to us by the EU Council.”

The country’s permanent representation to the EU does publish a “transparency register” of meetings with lobbyists.

However the data on its website only goes back to the start of this year, and the entries are severely limited — with, in the vast majority of cases, no details provided on the topics discussed.

The register for this year, for example, shows a meeting back in March with a Facebook representative, Aura Salla, the adtech giant’s managing public policy director and head of EU affairs — but there are no details about the meeting’s contents.

The Slovene list also records a number of meetings with third party business associations that are affiliated with tech giants and known to parrot their talking points. But, again, no detail is given about what the lobbyists were pressing for.

Portugal’s permanent representation to the EU also publishes a transparency register of lobby meetings with its ambassadors.

Similarly, though, its list is partial — only dating back to 2020 (with no details provided on any of the listed meetings).

Portugal’s register also records a meeting between its ambassador and Facebook’s Salla.

‘Look at the size of our lobby network!’

Google’s public messaging about people’s information typically features at least one claim that it “cares deeply for user privacy and security”.

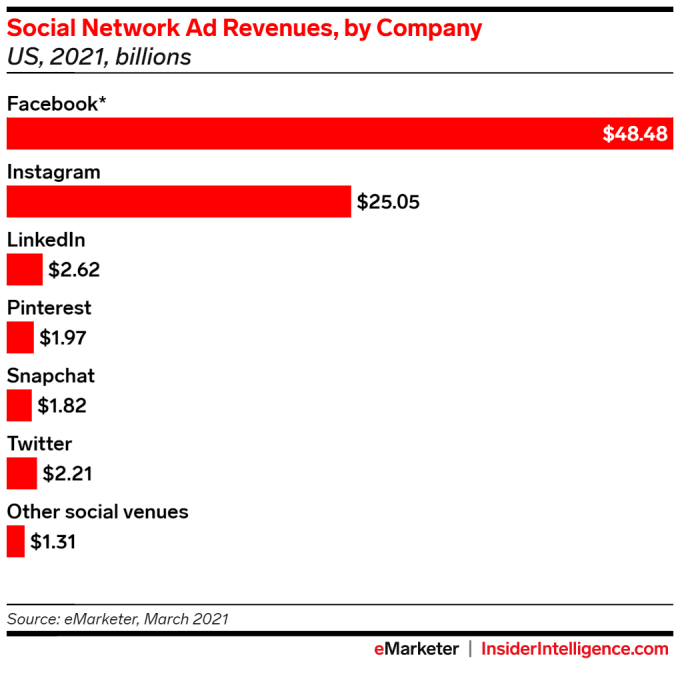

Google does certainly cherish your data. Of course it does. Your information is the fuel for an ad targeting empire that raked in $182.5BN last year.

Google Cloud generated a small slice of that ($13BN). Its ‘other bets’ division added a morsel too ($657M). But almost all of Google’s vast profits come from targeting advertising at eyeballs based on what it knows about the mind behind the peepers.

TechCrunch asked Google about the discrepancy between fine-sounding claims that fall from its execs’ lips — such as CEO Sundar Pichai telling US lawmakers last year that Google “deeply cares about the privacy and security of our users” (as he was being accused of destroying anonymity on the Internet); or the text of Google’s own privacy policy, where it writes that it: “work[s] hard to protect your information and put you in control” even as it applies labyrinthine settings that make it almost impossible to opt out of tracking and remain opted out — vs allegations in the States’ lawsuit of backroom dealings to derail European privacy legislation.

In response, Google sought to divert attention by claiming other businesses were also lobbying against ePrivacy and, therefore, that it was “not alone” in opposing the update — using a similar tack to the strategy Facebook applies when Europeans talk about banning microtargeted ads altogether; or even just enforcing current EU laws against Facebook (per Clegg this would ‘kill SMEs’ and be “disastrous” for Europe’s economy).

Interestingly, the statement that Google’s spokesman sent us on its anti-ePrivacy lobbying contains a centerpiece reference to an open letter, released in May 2018 — which the tech giant fastidiously observes was signed by “56 business associations from multiple sectors — not just tech”, seemingly presenting a united front to urge EU Member States to apply the legislative brakes.

Here’s Google’s claim:

“The tech industry was not alone in raising concerns with the ePrivacy regulation as it was then drafted, as a broad range of European organizations — from news to automotive to banking to small business — raised their voices in multiple public and private statements on the same issues. In May 2018, 56 business associations from multiple sectors — not just tech — published an open letter asking for ‘more time’ to assess the draft’s impact ‘on all sectors of the economy’ given the simultaneous arrival into force of the GDPR.”

“We supported the industry in asking for time on ePrivacy so that we could all assess the impact of the GDPR and get that right, first. We also raised our concerns directly with policymakers in our meetings with them over multiple years,” Google’s statement goes on, apparently admitting to extensive lobbying.

The statement ends with a segue into a claim of (Google’s own) GDPR compliance — combined with the subtle suggestion that any privacy abuse would therefore be the fault of third parties that plug into its ad ecosystem (ohhai publishers!), as Google writes: “We’ve invested heavily in building our products to be private by design, secure by default, and compliant with Europe’s GDPR. As well as working on our own compliance, we’ve launched tools to support our partners’ efforts.”

Google’s claimed ‘compliance’ with GDPR ignores the fact that its adtech business is the subject of multiple complaints (not to mention wider antitrust investigations) in the region. Some of these complaints have spent years sitting on the desk of Ireland’s DPC — which continues to face accusations of impeding effective enforcement of the regulation. (The country’s low corporate tax economy has attracted scores of tech giants — so tech industry interests may be viewed as generally aligned with Irish interests.)

Google’s compliance claim also glosses over a $57M GDPR fine in France, at the start of 2019 (when its EU business hadn’t yet restructured to put users under the jurisdiction of Ireland on data protection matters) — a fine Google was handed for failing transparency requirements, meaning the consents it claimed hadn’t actually been legally obtained.

It also omits a $120M fine Google got at the end of last year under current ePrivacy rules — for dropping tracking cookies without consent (also from France’s CNIL).

It is blindingly obvious self-interest for Google to want to gut ePrivacy.

Nonetheless, it’s interesting the tech giant reaches for a fig-leaf defence for its lobbying that tries to dilute attention by claiming multiple other businesses feel the same way too. (Not to mention how it has specifically maneuvered publishers into an invidious position where are supposed to shield its adtech empire from legal risk around privacy abuse because Google requires these ‘partners’ obtain impossibly broad ‘consents’ from users for the ad targeting that Google makes such a handsome return on… )

Sure, some other business than Google/tech giants also don’t like ePrivacy.

But more missing context here is how big tech’s lobbying in Europe — pegged at eye-watering levels in recent years — has led to the creation of a sprawling, obfuscated lobby network where affiliated third parties are happy to parrot its talking points in public while, behind closed doors, accepting its checks.

A report this summer by two civil society groups, (the aforementioned) Corporate Europe Observatory along with Germany-based LobbyControl, found Google topped the lobbying list of Big Tech big spenders in the EU — with Mountain View shelling out €5.8M (~$6.7M) annually on trying to influence the shape and detail of EU tech policy.

But that’s likely just the tip of Google’s policy influence spending in Europe.

It looks to be the same story for all of GAFAM: Facebook (€5.5M annually); Microsoft (€5.3M); Apple (€3.5M); Amazon (€2.8M) — although Google and Facebook, the Internet’s adtech duopoly, top the list of big spenders in the digital industry.

The report highlights how big tech’s regional lobbying relies on an obfuscated network of third parties to “push through its messages” — including think tanks, SME and startup associations and law and economic consultancies — with platform giants exerting their influence by providing funding via sponsorships or membership fees.

Unsurprisingly, this policy influence network appears to have an outsized megaphone as a result of the wealthy company it keeps: Per the report, the lobbying budget of business associations lobbying in Europe on behalf of big tech “far surpasses that of the bottom 75 per cent of the companies in the digital industry”.

Or, put another way, the smallest and least well-funded players — individuals, civil society and businesses/startups with privacy-preserving approaches that don’t align with the surveillance model of big adtech — are having their views drowned out by adtech astroturfing.

“The rising lobby firepower of big tech and the digital industry as a whole mirrors the sectors’ huge and growing role in society,” the report notes. “It is remarkable and should be a cause of concern that the platforms can use this firepower to ensure their voices are heard — over countervailing and critical voices — in the debate over how to construct new rules for digital platforms.”

It’s notable that big tech also directly funds a number of startup associations — which may (otherwise) be seen by policymakers as dissociated from platform giants.

Google’s entry on the EU’s Transparency Register notes sponsorships of Allied for Startups, for example. And the advocacy organization’s website does at least disclose what it describes as “sponsorship” by a “Corporate Board” — which as well as Google includes Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft, among other platform and digital giants.

(“We are proud to be sponsored by our Corporate Board. It supports our activities, as selected by our members, but has no voting rights,” is the official Allied for Startups line on taking funding from tech giants while claiming to represent the interests of startups free from the influence of its platform giant funders.)

Links between big tech and a sprawling array of worthy sounding associations and business alliances are often far less plainly disclosed. The report emphasizes that affiliations are frequently fuzzed or not disclosed at all — thereby concealing “potential biases and conflicts of interest”.

“We still don’t have a complete picture of this network,” the report further warns.

TechCrunch shared the list of signatories in the open letter cited by Google as cover for its anti-ePrivacy lobbying with the two transparency organizations to ask for their verdict on how ‘clean’ it is — i.e. from a Google and/or big tech influence point of view.

Both confirmed that many of the listed groups have some form of affiliation with Google and/or other tech giants.

Margarida Silva, a co-author of the aforementioned big tech EU lobbying report, said a “quick check” of the list of signatories turned up 28 organizations that count Google as member or sponsor.

“With direct links to 28 out of 57 signatories, Google’s footprint is very clear here,” she told TechCrunch, adding: “The majority of the list is made up of lobby associations for big tech (i.e. EDIMA, CCIA, ITI, DigitalEurope, IAB), plus national level business associations that often have big tech as members.”

Silva also highlighted that some of the signatories are from other sectors (rather than tech) — including car manufacturers and publishers. But on that she pointed to the organization’s earlier findings, when it examined ePrivacy lobbying directly — and identified what she said was “a strong push by big tech [that was] matched with intense lobbying by telecoms and publishers and even other sectors who also want to benefit from surveillance advertising”.

So, again, big adtech’s wider influence is hard at work exerting an anti-privacy pull that’s redefining the center of gravity for other industries.

When we raised Google’s comments about working “hand in hand” with other tech giants in its lobbying against privacy, Silva also suggested that “coordination seems very likely”.

“GAFAM are members of the big tech lobby groups (e.g. EDIMA) who were themselves active pushing back against ePrivacy”, she noted, adding: “Usually these forums are useful for their members to discuss, agree shared approaches or delegate some lobbying activities.”

LobbyControl’s Max Bank also took a look at the list of signatories — and his pass turned up “at least 23” with an affiliation with Google — i.e. meaning the tech giant is “a member and most probably provides a member fee”.

Per the pair’s analysis, examples of Google-affiliated associations whose names appear on the open letter include industry-wider groups like Digital Europe, BusinessEurope, EDIMA and the Computer and Communications Industry Association — but also regional industry bodies like the Confederation of Danish Industry, Technology Industries of Finland, Digital Poland and Tech in France, to name a few.

Across Europe, big adtech’s reach has grown long indeed.

“Not all of these memberships are reflected in the EU transparency register,” Bank added. “It reflects again the in-transparent and powerful lobby network Google has in the EU.”

Talking of powerful lobby networks, it’s instructive to return to Facebook’s recent flashy rebrand and ‘pivot’ to “building the Metaverse”, as it describes its plan to extend its ad tracking model’s grip on people’s attention for decades to come.

This looks very interesting from a regional lobbying point of view because Facebook’s announcement included an explicit bung for Europe — with the adtech giant saying it would be hiring 10,000 highly skilled tech workers to develop the metaverse “within the European Union”. (And where exactly in the EU those jobs end up could be an instructive way to map Facebook’s regional influence network.)

The timing here is key — with EU lawmakers busy negotiating the detail of the next suite of EU digital regulations — including rules that are exclusively set to apply to big tech (aka, the DMA)…

So the question for the bloc is whether Member States’ narrow, local interests will continue to allow EU citizens’ fundamental rights be traded away on the vague promise of jobs for a few techbros…

(Going on Facebook average wage data in the EU in recent years, it’s maybe offering to spend a little over €1.5BN on this spot of local hiring — or just a few hundreds of millions per year until 2026.)

A gaping hole in EU transparency

The statement Google sent us in response to public disclosure of its anti-ePrivacy lobbying ends with what sounds almost like a (micro)apology on being caught claiming to champion consumer privacy in public while simultaneously pressing lawmakers to stall progress on the self-same subject behind closed doors.

To wit:

“As lawmakers debate new rules for the internet, citizens expect companies to engage with legislative debate openly and in ways that fully account for the concerns of all of society. We know we have a responsibility to take this understanding into our work on internet policy, and consistently strive to do so.”

But, essentially, even Google’s own assessment of how it operates is an expression of never actually achieving full accountability. Which also looks instructive of how big tech works.

Meanwhile, the ePrivacy Regulation remains undone — more than four years since the Commission’s original reform proposal (all the way back in January 2017).

The blockage has centered on the European Council — the EU institution that’s (mostly) made up of heads of governments from the 27 Member States — which has spent years failing to agree a negotiating position, meaning the Regulation couldn’t move through to discussions with the Parliament to arrive, very likely amended, at some kind of consensus and ultimate adoption.

An EU source on the European Council declined to comment on the States’ lawsuit’s allegations of Google celebrating success in stalling ePrivacy, saying only: “Negotiations on this regulation are ongoing, and I cannot provide you with more information or comments.”

A European Commission spokesman also declined to comment.

But the EU’s executive, which was responsible for drafting the original proposal, told us it stands by it — and also sounded a warning against deviation from core objectives, writing: “As far as the Commission is concerned, we stand by our proposal and remain committed to supporting the European Parliament and the Council in the trilogues to find a compromise, in keeping with the objectives of the Commission’s proposal.”

There were disagreements in the Parliament over ePrivacy. But MEPs did arrive more quickly at a negotiating position. So the real culprit for stalling ePrivacy is the Member States.

The European Parliament’s rapporteur on the ePrivacy trilogues, Birgit Sippel, declined to comment on Google’s lobbying against the file. But we also contacted a couple of shadow rapporteurs — who were more open in their views.

MEP Sophie In ‘t Veld said that while lobbying transparency around EU institutions has improved in recent years there is still a major blindspot when it comes to corporate influence ops targeting Member States’ governments directly.

“The lobbying to national governments is invisible,” she told TechCrunch — dubbing it “a big gaping hole in transparency.”

“In a way it’s not surprising,” she said of ePrivacy. “There are big interests at stake, everybody’s always trying to influence the lawmakers — it’s interesting to see how worried [big tech] are up to the point that they feel that they have to join forces but it also confirms what we are always saying that the Member States are much more susceptible to this kind of corporate and industrial interest.”

“[ePrivacy] has been stuck in Council for a very long time and it’s always the same problem,” In ‘t Veld added. “The European Parliament is of course made up of different political groups, political families, political convictions — but ultimately we always find a common line. In the Council you never know, it’s opaque… it’s not even related to political color but they’re just a lot more susceptible to corporate and industrial lobbying for reasons I fail to grasp.

“They always, systematically, take a line which is closest to big industry, to the big international corporations, big tech, American big tech — which I find even more surprising. But that’s what they do systematically. So the fact they are being successfully lobbied is not surprising.”

She pointed out that the situation was the same when the EU was negotiating the GDPR — and other pieces of pan-EU legislation, like the law enforcement directive.

So the lobbying itself is nothing new (even if the scale keeps stepping up).

However, given the blistering pace and iterations of technology change — and the market power that has accrued to a handful of the biggest data-mining giants — legislative logjams affecting the passage of digital regulations start to look like a fundamental crisis for the rule of law, as well as for Europeans’ fundamental rights.

“GDPR in its final version was not what big tech had in mind. So the European Parliament is doing its job — but it’s very annoying that we always have to push back against the Council,” said In ‘t Veld, adding that perpetual stalling is unfortunately a common Council tactic.

“Their tactic is to not actually negotiate or debate — they just stall, they just say oh we can’t agree,” she said, adding: “There are so many files which have been blocked in Council for years — in some cases ten, 15 years — they just block, it’s their tactic, rather than trying to find solutions.”

Again, though, in the digital sphere this delaying tactic looks particular concerning.

And given the huge vested interests ranged against other nascent EU digital regulations, like the DSA and DMA, how can the bloc confidently claim it can regulate Internet “gatekeepers” — when it can’t even stop big adtech’s lobbyists from stalling its own lawmakers?

MEP Patrick Breyer, another rapporteur on the ePrivacy file, was equally withering in his assessment of the ePrivacy situation — saying that while trilogue negotiations have started, the Council has “succumbed to lobbying to a degree that rather than accept this it would be far better to abandon the reform altogether”.

“Industry (including the ad business and publishers) and national governments have colluded to block ePrivacy rules which the European Parliament wants to ban surveillance tracking walls and eliminate the cookie banner nuisance by making browser signals mandatory, among other things,” he told TechCrunch.

“This year Member States have adopted a position which doesn’t deserve to have privacy in its name. I have more on this dossier on my homepage.”

“Shame on national governments for succumbing to this lobbying,” Breyer added. “The online activities of an individual allow for deep insights into their (past and future) behaviour and make it possible to manipulate them. Users have a right not to be subject to pervasive tracking when using digital services.”

The reason why lobbying is “so easy to do is precisely because Council members refuse to publish lobby meetings (unlike, to some degree, Parliament and Commission)”, he added.

With lines in to such an extensive third party influence network in Europe, and so many opaque avenues of approach to tickle friendly national governments across Europe until they adopt helpful policy positions — or else spend years refusing to adopt a position at all — it’s not hard to see how Google bought its business years more profits by delaying ePrivacy.

Postcards from Pichai’s European tour

Without full transparency into both the number and content of lobby meetings between EU Member States and tech giants we are left to speculate on how exactly adtech giants like Google went about derailing legislative progress.

Perhaps by targeting certain ‘friendly’ governments — dangling the prospect of a little local investment, either in tech infrastructure or jobs (or both), in exchange for not ‘rushing’ (aka stalling) the negotiations.

On this front it’s instructive to look through press photography of the Google CEO, back in 2018 and 2019 — when Pichai took the time to personally tour a number of European cities — and can be seen in conversation with heads of state, including France’s president Emanuel Macron, who he met in Paris in January 2018. (In the below shot at least, Macron does not look very friendly though.)

There is also an intimate tête-à-tête with Poland’s prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, in what was surely a very chilly Warsaw in January 2019.

In another in-person visit, Pichai held a joint press conference with a beaming Finnish prime, Minister Antti Rinne, in September 2019 in Helsinki.

In Helsinki the Google CEO announced a plan to invest €3BN to expand its data centers across Europe over the next two years, supporting a total of 13,000 full-time jobs in the EU per year. The Google announcement also trailed included the construction of more than €1BN in new energy infrastructure in the EU, including a new offshore wind project in Belgium; five solar energy projects in Denmark; and two wind energy projects in each Sweden and Finland, according to press coverage at the time.

Which does rather smell like ‘pork barrel politics’, big tech style (i.e. with glossier press photography).

[gallery ids="2224713,2224723,2224724,2224749"]

Pichai also made it to Berlin in January 2019 to cut the ribbon on a new policy office for Google Germany.

Press pics show him standing smiling alongside Philipp Justus, Google’s VP for Central Europe, and Annette Kroeber-Riel, its senior director public policy and government relations — ahead of an official opening that night in which Berlin Mayor, Michael Muller, was slated to attend.

We’re sure the canapés and cava flowed freely.

LobbyControl’s Bank says public criticism has forced Google to be more open about its “in-transparent” lobbying — highlighting a campaign the organization ran last year in Germany calling for the tech giant to publish its local lobby network. (He said Google did make some disclosures — but only after that public pressure.)

The lobby network on Google’s EU transparency register was also only included after public criticism, per Bank.

In a blog post about its campaign last year, LobbyControl noted ongoing disclosure limitations that prevent the full picture of Google’s regional influence from being seen. “In its answer, Google lists the organizations of which the group is a member in Germany. This ranges from the Atlantic Bridge to the Federal Association of German Startups and the Digital Association Bitkom to the Economic Forum of the SPD and the Economic Council of the CDU. For Europe, Google refers to its entry in the European transparency register,” it wrote.

“However, we also asked Google about the organizations that are financially supported by the company. Unfortunately, we have not received an answer to these questions. Google continues to deny comprehensive transparency of its lobby network in Germany and the EU.”

It also noted that in the US Google publishes what it describes as “a more comprehensive list” vs its influence ops in Europe.

“There the company lists 94 trade associations and member organizations as well as 256 ‘third party organizations’,” it wrote. “In the US, there are on average 2.5 other organizations for every member organization that Google supports financially without membership.

“For Germany and Europe, too, we can assume that, in addition to the disclosed memberships, there are also numerous organizations that receive money from Google. Google keeps this information under lock and key.”

TechCrunch contacted a number of Member States’ permanent representatives to the EU to ask for a response to Google’s memo about its “successful” lobbying to freeze ePrivacy.

The permanent representations to the EU of France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Finland, Poland, Sweden and Denmark did not respond to questions about their position on the file — nor did they confirm whether Google had lobbied them (directly or indirectly) to stall the legislation.

In fact we got no response to these requests at all.

Some representations do publish (partial) lists of lobbying meetings, as we have noted. But this is even a sketch as big tech can route around even those limited disclosures by approaching national governments locally, either directly to national governments or through their vast influence network of third parties.

Sometimes — presumably when a giant like Google feels a particular piece of legislation poses enough of a risk — it might even send in its own CEO to personally petition a government or head of state. Divide and conquer as they say.

EU digital rules in the deep freeze?

The adtech influence network across Europe is quite the thing to behold, even just looking at the (partially) visible tip.

An iceberg seems an appropriate visual metaphone for what Google and other tech giants have been busily developing behind closed doors across the EU to put a deep freeze on legislation that could disrupt their surveillance capitalism in a region with ~450M pairs of eyeballs — and the world’s most well-established set of digital privacy rules (at least on paper).

Politico‘s report last year on Amazon’s lobbying memo described the document as offering “a snapshot of the company’s modus operandi in the EU” — highlighting references in the text to how it channels its positions through “a range of different lobby groups including tech groups CCIA and DigitalEurope, as well as marketing group FEDMA”. All of which now sounds very familiar.

“Amazon lobbyists said in the document that they would focus on lobbying Council telecoms attachés,” the report went on, suggesting another link between the interests of US tech giants and European telco giants (after all, US telcos don’t have the same regulatory limits on what they can do with users’ data). “They said that they had met with ministries in Madrid, Rome and Paris and noted that Spain was ‘now openly outspoken against the proposal and aligned with our views’ and that Italy was likely to follow suit.”

So the playbook for big tech to play EU policymakers off against each other looks firmly established. Even embedded.

That does not bode well for the passage of a suite of ambitious new EU digital regulations — from the aforementioned DSA and DMA to an Artificial Intelligence Regulation which will provide controls for high risk applications of AI; or broad plans to expand the rules around data resharing (with claimed privacy protections); or even planned legislation for online political ads, given the risks that data-driven adtech can pose to democratic processes.

Still, revelations that GAFAM has been privately celebrating its success at derailing updates to the bloc’s rules may not sit easily with all EU Member State governments.

France and the Netherlands have — at least in public pronouncements — broken ranks somewhat, pressing for Brussels to have greater powers to reign in big tech for example.

There is also pressure building within a number of Member States over the need for a competitive reboot of digital markets — to ensure a better outcome for consumers and competition. So even if EU legislation fails, big tech may face a patchwork of rules clipping its wings at a local level.

On this front, Germany is ahead: It has already updated its digital rulebook to bring in ex ante powers and the FCO has a raft of procedures open to assess tech giant’s market power — including into Google and Facebook. If it confirms they have what the law dubs “paramount significance for competition across markets” the next steps would be bespoke antitrust interventions.

France has also been banging the drum for national and European ‘digital sovereignty’ in recent years — and its competition watchdog stung Google with a $268M fine over adtech abuse this summer (albeit extracting interoperability commitments which Google will probably be more than happy to comply with if they further entrench its surveillance model).

France’s national stance aligns with rhetoric from the (French) EU commissioner, Thierry Breton, who is responsible for the bloc’s internal market policy — and is also fond of talking up la souveraineté — and/or warning of the balance of power between different global blocs “hardening“.

And, this summer, French president Macron had some bold-sounding words about breaking up US tech giants — making his utterance in front of a tech audience, no less.

So one looming development for the ePrivacy file — which could auger at least a shift of tone — is that France takes over the rotating Council presidency from Slovenia next year.

France has named digital regulations as among its priorities during the six-month stint when it will be steering activity. So there may be a small window of opportunity to unchoke big tech’s choke-hold on ePrivacy. Although France’s list of claimed priorities is long, and there’s scepticism over how much it will actually be able to get done.

In ‘t Veld, for one, isn’t holding her breath — saying her expectations of the rotating presidency mechanism are “limited”.

She suggests a better solution for fixing blockages in the EU’s legislative firepower might be to strategically withhold portions of the budget — as a tool to concentrate Member States’ minds on, well, the common good of all Europeans. (Though she says that such talk can make some of her fellow MEPs “nervous”.)

“I’m very tired of the way that the Council operates. They have to start taking responsibility,” she adds. “Haven’t we learnt anything from the last couple of years? Look in the last weeks — just today — about Facebook. Think about Cambridge Analytica. Haven’t they learnt anything?”

While adtech giants splash millions on bending the ears of EU policymakers, civil society organizations don’t even have a fraction of the resource to marshal to defend European’s fundamental rights from such self-interested attacks.

It is, in short, not a fair fight. But it’s a fight for the future of so much — perhaps for the very substance of society itself — as connectivity inexorably expands the net of data-driven surveillance that losing it doesn’t even bear thinking about.

Privacy is, on the one hand, inherently personal — which can make articulating its fundamental importance a challenge, since it is so very multifaceted and multidimensional. But, hey, you sure as hell miss it when it’s gone. Collectively, it is also a shield that helps keep people and communities aligned towards a civilized, common goal by eliding difference in a way that fosters good will, social cohesion and consensus.

Again, if we’re all broken out so we can be badged and branded, manipulated and jerked around — and, sure, set against each other if it happens to sell more stuff — aka, atomized by adtech — it can quickly become a very different, polarizing story. One that doesn’t have a happy-looking ending for democratic civilization.

And with giants like Facebook already making a pitch to co-opt interoperability to its own ends by embedding the surveillance model at the core of an ‘ad-ternative‘ immersive digital reality (‘the metaverse’), time is fast running out to save the European model — of fundamental rights and freedoms — from the deep-pocketed corporate lobbyists now ranged against it.

Remember: If the shiniest version of the future big adtech has to sell comes straight out of a sci-fi dystopia — and stars Nick Clegg trying to buy off the European model for ‘10,000 jobs’ — it really is time to wake up and show big tech’s lobbyists where to find the door.