B2B marketplaces have been in many ways slower to modernize than their consumer counterparts when it comes to e-commerce. Today a startup that has been a trailblazer in that space is announcing some funding from a key investor that underscores how this is changing and the opportunities that exist as a result. Profishop, which has built a storefront selling products for business and industrial environments — think power tools, workbenches, and agricultural and catering equipment, but also office supplies — by working directly with wholesalers to build a “just in time” platform for ordering and distribution, has raised $35 million, an equity investment that it will be using both to continue expanding its business and platform in Europe as well as further afield.

Based out of Bremen, Germany, Profishop is now active in 13 markets with its German storefront currently its biggest; earlier this year it also spearheaded efforts to break into the U.S. Arasch Jalali, the CEO who co-founded the company with Anna Hoffmann (the CTO, who also happens to be Jalali’s wife), said that the company cleared $100 million in sales with 500,000 customers last year, and it’s on track to more than double those numbers this year.

“We have grown 100%-120% year-on-year every year since starting,” he said.

That growth rate is likely what got the company on the radar of Tiger Global — the storied late-stage investor that has been getting more active in Europe and in making earlier-stage bets in recent times — which is the sole investor in this round. Profishop has been active for about a decade and has been profitable in that time. In fact, before this it had only raised a seed round of an undisclosed amount, from Takkt and Howzat, according to PitchBook data.

The initial inspiration for Profishop, and its subsequent growth, is a textbook example of a classic startup story.

Jalali tells me that he first thought about the concept for Profishop when working in his first job out of university, a B2B business, where he saw first-hand how antiquated processes were for sellers and buyers in the market.

It was 2010, but by and large businesses in the B2B space in Germany were still using printed catalogues to lay out to potential customers everything that they had for sale, and the rest of the process for buying was equally analogue: the product purchasing process, including contacting a business to get price estimates and stock checks, were made by fax, comparing different products from different places also involved… comparing different faxed documents.

It was also a tedious process that typically involved middlemen-type players that slowed things down and brought more cost into the system: typically manufacturers of supplies worked with wholesalers, who then might sell directly to businesses, but might also work with further retailers who then finally sold to business customers.

In that context, the bar for entry into disrupting that state of affairs was paradoxically both very high and very low.

Low, because there was so much to do: even setting out to digitize those catalogues, or creating an online payment system would be a significant step towards modernizing — forget about more sophisticated ideas around better search algorithms, more tailored marketing, smart pricing, better logistics services, analytics for suppliers to understand what customers want or do not want to buy, and so on.

High, because it can be hard to convince companies entrenched in traditional ways of doing business to switch things up. And Profishop’s idea for how to switch things up was relatively revolutionary: its idea was to tap directly into the German manufacturing industry to work directly with the companies making products, and to set up a system whereby when a business customer purchased a product, Profishop would pass on the order directly to that manufacturer, who would drop-ship it directly to the business making the order. This “just in time” approach would mean no warehouses and no stock buying-in for Profishop, which was building a platform to position itself as a facilitator between the other two parties.

Jalali said that initial efforts to work with manufacturers were very slow to start with. When it opened for business online it had only five products listed, including a workbench and a locker. And he and his wife had zero experience in e-commerce. “We hadn’t even done any marketing,” he said. “But we got our first sale in 45 minutes.” In fact they hadn’t even had the time or funds to set up stock so the “just in time” first sale almost happened by default.

It was hard-going at first to talk to wholesales and sell them on the idea. “No one believed in us, and some even just laughed in our faces and told us this would never work.”

“We onboarded 20 new manufacturers in our first year,” he said. This year it will be 500 “and it will soon be 5,000.”

Ironically, one of the early nay-sayer brands is now one of its biggest partners. In total Profishop has some 1,600 wholesales and offers 1.6 million items for drop shipments.

In building out this business, Profishop has tapped into some interesting, larger socio-economic trends.

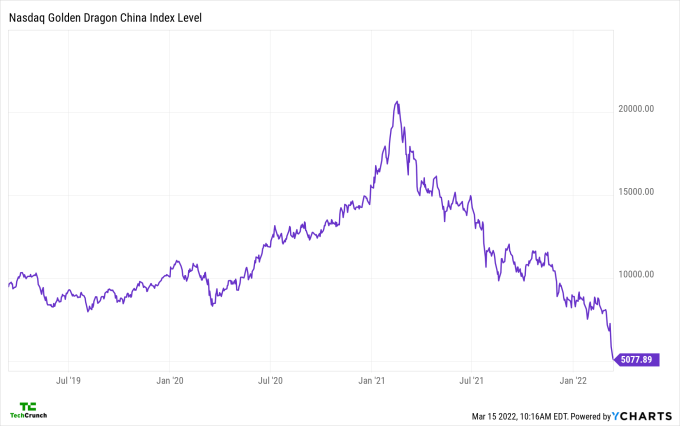

One of the biggest has been the role of manufacturing and how it has shifted over the years. For decades, a lot of global manufacturing has moved over to Asia, and specifically China, which has invested a huge amount in becoming the global leader in this space. Profishop’s whole business model is predicated on manufacturing happening locally to fit its logistics and fulfillment model. Indeed, it currently has no deals with manufacturers further afield.

This has meant that it’s been fostering a new market entry point and business opportunity for more localized manufacturing businesses, but that wasn’t always the case. Jalali noted that in some instances, the factories it visits prior to working with a company were dormant, the company having switched to shipping in supplies from China and using its factories more like warehouses.

“We would ask, ‘Where are your employees? Your site says you have 250 of them.’ They would answer that they now order everything from China,” he said. “But that has changed.” He said that part of the reason is economic: prices have gone up, both in terms of the costs needed to maintain manufacturing quality, but also the logistics and shipping costs for those goods, some 5x on average between 2020 and 2022, he said. “It has meant that a lot are thinking about bringing manufacturing back to Euope or Easter Europe. But it’s a process. It’s hard work but they are thinking about it.” The U.S. business, in part because of the size of the country, has Profishop working with a logistics company to help handle drop shipments, and as it expands in Europe this is likely to be a part of the equation there, too.

In terms of competitors, there are a number of other companies moving deeper into B2B, and no less than major marketplaces like Amazon and Alibaba are already big players (there, it’s wholesalers who do the selling to buyers). Even the name Profishop — a portmanteau of “professional” and “shop” — is not trademarked and is already being used by a specific brand to sell its industrial equipment online directly. It’s a crowded space, but one where building out relationships and offering the more direct option to manufacturers (no wholesalers involved) appears to be giving Profishop a big opening.

“The long-tail of equipment purchases for businesses is often unmanaged and offline. Profishop’s B2B marketplace brings this spend online, allowing customers to easily manage and source more than 1.5 million high-quality SKUs on one platform,” said Griffin Schroeder, a partner at Tiger Global, in a statement. “200,000 active buyers in Europe utilize Profishop, and we are thrilled to partner with Arasch and Anna to help them expand the business internationally.”