China is one of the world’s wealthiest digital economies today, with a hardware supply chain that is unrivaled and a panoply of prominent and massively profitable companies like Alibaba, Tencent and ByteDance taking a leading role in the world. Yet, all of this cutting-edge innovation rests on a forty-year-old solution to one of the great computing challenges: the development of Chinese word processing.

Beginning in the early 1980s, China dramatically expanded its computing purchases from the United States and the West, importing just 600 foreign-built microcomputers in the year 1980, as compared to 130,000 in 1985. Companies in the United States, Japan, and Europe clamored to get in on this “buying binge,” as one observer called it.

There was a major problem, however, both for potential Chinese computer users and Western manufacturers: no Western-built personal computer, printer, monitor, operating system, program, or otherwise was capable of handling Chinese character input or output—not in the early and mid-1980s, anyway, and certainly not “out of the box.” Without some major overhauls, mass-manufactured personal computers were effectively useless for anyone wanting to operate in Chinese.

One of the most important reasons was the problem of memory—specifically the memory required for Chinese fonts. At the advent of Latin alphabetic computing, Western engineers and designers determined that a font for English could be built upon a 5-by-7 bitmap grid—requiring only 5 bytes of memory per symbol. Although far from aesthetically pleasing, this grid offered sufficient resolution to render the letters of the Latin alphabet legibly on a computer terminal or a paper printout. Storing the 95 printable characters of US ASCII required just 475 bytes of memory—a tiny fraction of, for example, the Apple II’s then 48K of motherboard memory.

To achieve comparable, bare-minimum legibility for Chinese characters, the 5-by-7 grid was far too small. When designing a bitmap font for Chinese, engineers had no choice but to increase the size of the Latin alphabetic grid geometrically, from 5-by-7 pixels to upwards of 16-by-16 pixels or larger, or at least 32 bytes of memory per Chinese character. The total memory required to store just the bitmaps (in either simplified or traditional form, but not both, and with no accompanying metadata) would equal approximately 256K for the 8,000 most commonly used Chinese characters, or four times the total capacity of most off-the-shelf personal computers in the early 1980s. All this, even before accounting for the RAM requirements for the operating system and application software.

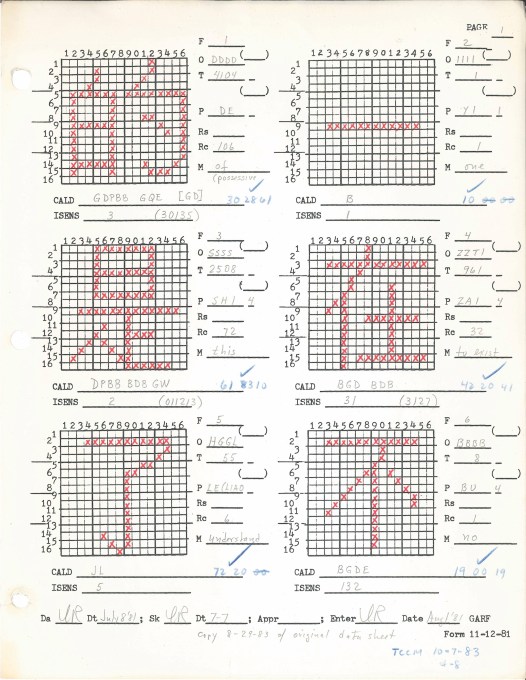

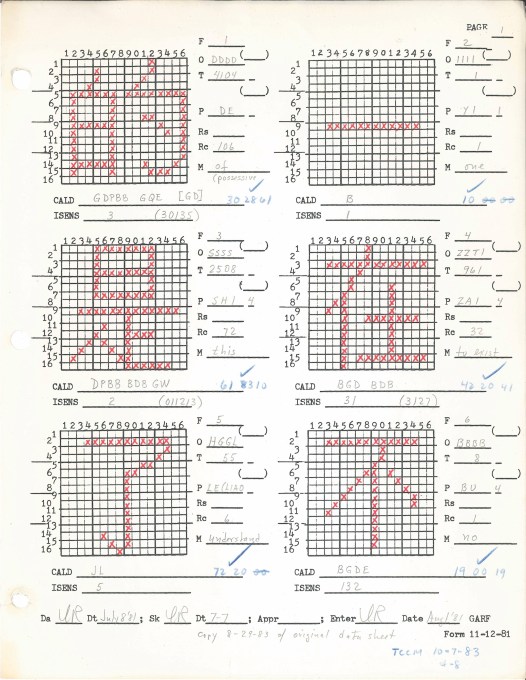

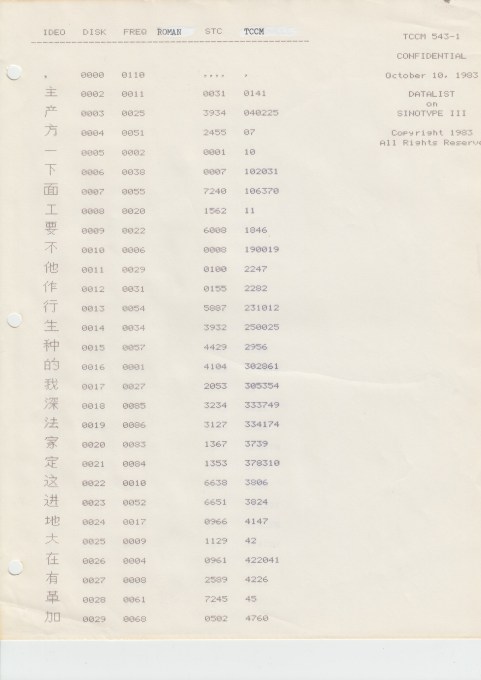

Draft bitmaps from the Sinotype III Chinese font, prepared prior to digitization. Courtesy of Louis Rosenblum Papers, Stanford University Special Collections.

Such is the context for one of the great engineering histories of modern computing, a tale of entrepreneurial daring and engineering ingenuity that provides a unique look into the global development of the digital revolution.

This is the first of two articles on TechCrunch in which I examine the Sinotype III, an experimental machine which was among the first personal computers to handle Chinese-language input and output. Built atop a store-bought Apple II—but outfitted with a custom-programmed word processor and operating system—Sinotype III served as a “proof of concept” which demonstrated how one could “translate” Western-manufactured computers into Chinese, and thereby open up a vast new marketplace.

In this first part, I will examine the profound technical challenges around computer memory, fonts, and operating systems faced by the creators of Sinotype III, and how they devised novel solutions to overcome them.

“The chutzpah of a newly minted graduate who had no immediate job prospects”

Our story begins with the Graphic Arts Research Foundation (GARF)—the organization where, arguably, Chinese computing was born. The Ideographic Composing Machine, also known as the Sinotype, was invented in the late 1950s by MIT electrical engineer, Samuel Hawks Caldwell with GARF funding. Following his untimely death in 1960, the project came to a standstill. During the 1960s and 1970s, the Sinotype project was kept alive by a number of different parties, including the Itek Corporation, RCA, and finally, GARF once again.

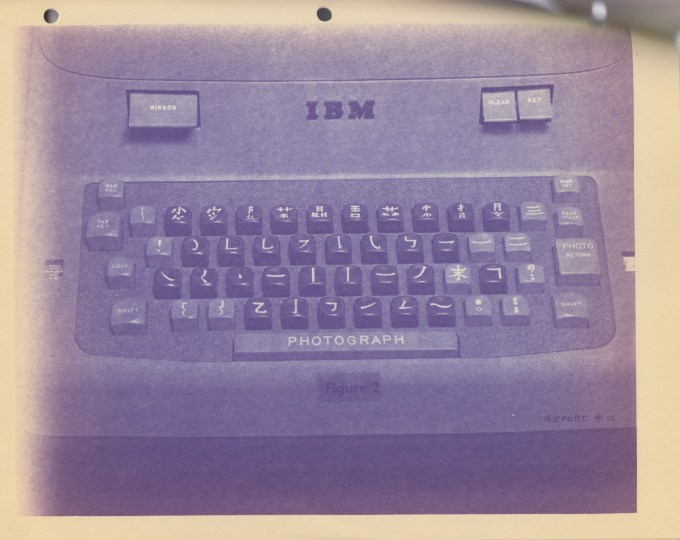

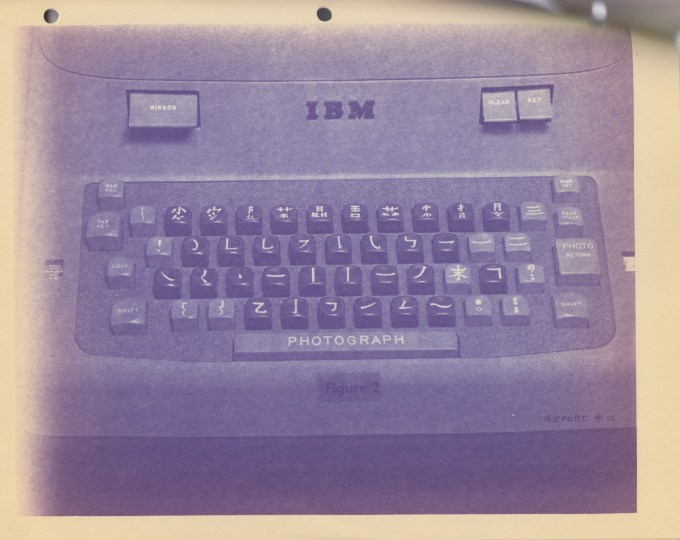

Keyboard of Sinotype I, designed by Samuel Caldwell in the late 1950s. Courtesy of Louis Rosenblum Papers, Stanford University Special Collections.

Sinotype’s homecoming was thanks in large part to one man: Louis Rosenblum. Born in 1921 in New York City, he was yet another member of the MIT family, graduating in 1942 with an undergraduate degree in Applied Math. Studying under Harold Edgerton, the world-renowned professor of Electrical Engineering (and who shot the famous “milk drop coronet” photo in in the 1930s), Rosenblum took a job at Polaroid immediately following graduation, working with Edwin Land on a variety of projects, including the development of instant photography. In 1954, he moved to Photon—where he worked on photocomposition of non-Latin writing systems. Deeply familiar with the late Caldwell’s pioneering work on Sinotype, Rosenblum effectively adopted the project, and revived it when he joined GARF as a consultant in the mid-1970s.

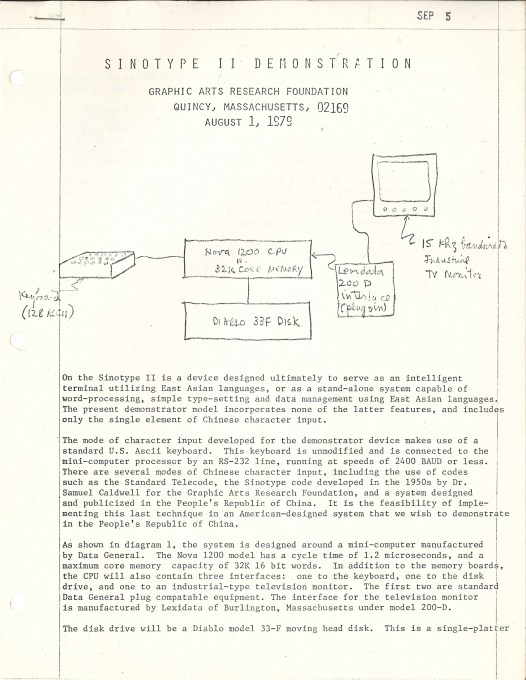

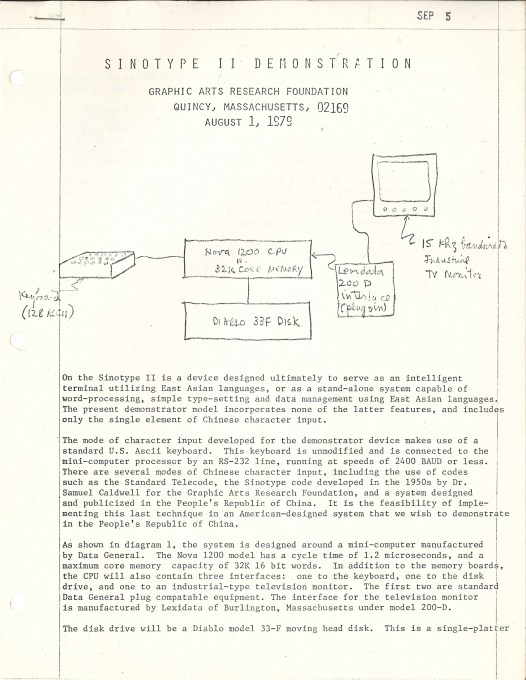

Diagram showing configuration of Sinotype II system, running on a Nova 1200 CPU. Courtesy of Louis Rosenblum Papers, Stanford University Special Collections.

GARF continued to work on the Sinotype project well into the early 1980s, by which point it had developed an advisory board featuring a host of renowned scholars, as well as those with deep China experience. Harvard linguist Susumo Kuno came on board; as did Richard Solomon, known for his pivotal role in Richard Nixon’s visit to the PRC in 1972 and then head of the Social Science Department at the RAND Corporation.

As stellar as this brain trust was, however, GARF’s major breakthrough on the Sinotype project—the leap from a minicomputer-based system (Sinotype II) to one based on a microcomputer (Sinotype III)—was catalyzed by a college student whose only experience at GARF to date was a brief, two-week gig working on data management for the Sinotype II project in 1979. He was Bruce Rosenblum, Louis Rosenblum’s son.

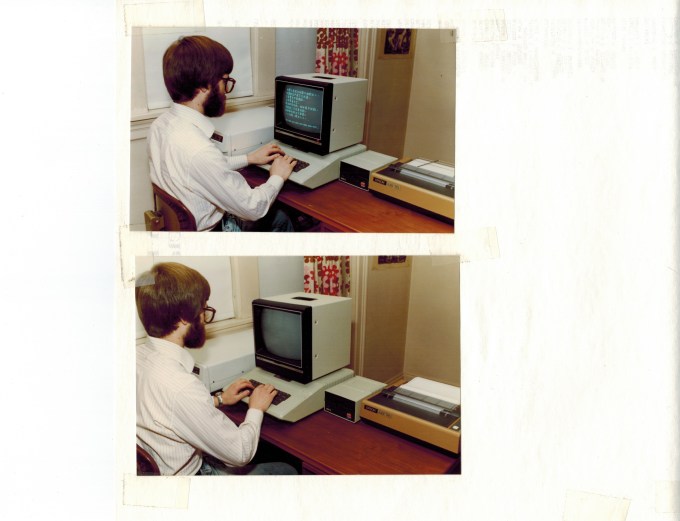

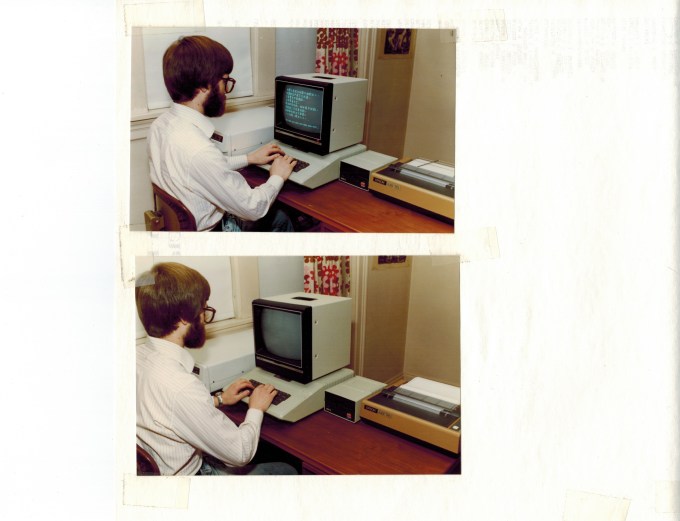

Bruce Rosenblum using the Sinotype III system. Courtesy of Louis Rosenblum Papers, Stanford University Special Collections.

As an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania and an aspiring photojournalist, Bruce was balancing his time between coursework and his role as Photo Editor for the independent student-run newspaper Daily Pennsylvanian. The paper was remarkably advanced in terms of the equipment it ran, as well as the deep expertise of the students in charge.

By the fall of Bruce’s junior year, the paper’s existing typesetting equipment (two Compugraphic typesetters) were on their last legs and needed to be replaced. Along with three of his student colleagues at the paper, Bruce assisted in the process of researching potential replacements, eventually settling on a combined $125,000 contract with two companies: Mycro-Tek in Wichita, Kansas, and Compugraphic, in Wilmington, Massachusetts.

As for the Sinotype project—one that Bruce was well aware of, thanks to his father, but with which he had no involvement—a pivotal moment came in early May 1981. Bruce had just completed his final exams, and stopped by the offices of the paper. His colleague Eric Jacobs was there, hard at work on a TRS-80 Model II personal computer from Radio Shack. Jacobs was contemplating how this microcomputer might be used to run the newspaper’s business operations. Bruce observed for perhaps thirty minutes, before heading on with his day.

Those thirty minutes stuck with him, however. “It was the first time I’d ever seen anyone work on a microcomputer,” Bruce recalled by email to me, “and those few minutes were the inspiration that triggered the whole Sinotype III project and eventually my career in computers.”

Later that same week, Bruce made a somewhat off-the-cuff remark in a phone call with his father. Referencing the immense cost of the Data General hardware GARF was then using to build Sinotype II, Bruce remarked that someone could probably program something equivalent or better on a microcomputer for a fraction of the cost—perhaps with as little as $10,000 worth of hardware, as compared to the more-than $100,000 price tag for the equipment GARF was currently funding.

His father was intrigued. Louis asked Bruce if he himself might be up to the task of programming such a machine. Bruce boasted no formal training in computer science, although he had worked intensively with computers in high school, and taught himself both PDP-8 assembly language and BASIC. “Sure,” he responded to his father’s query with “the chutzpah of a newly minted graduate who had no immediate job prospects.”

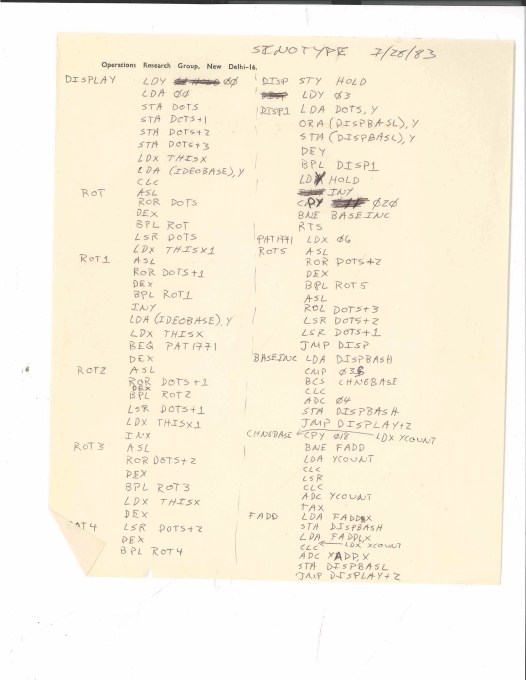

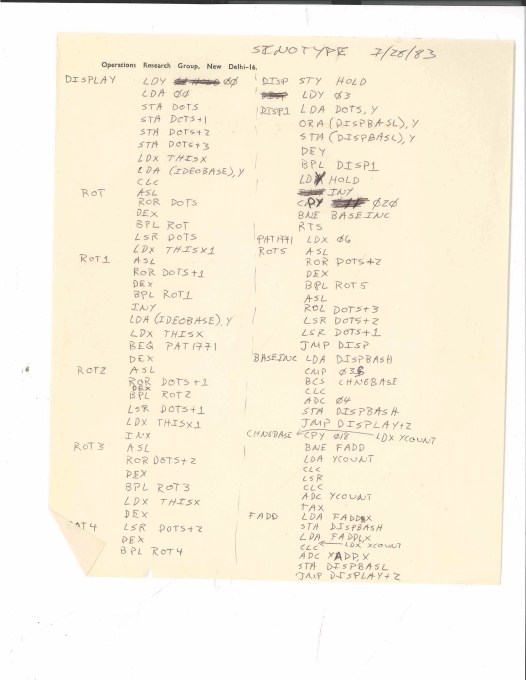

During his world tour, Bruce Rosenblum continued to work on the Sinotype III project, including on notepaper from New Delhi. Courtesy of Louis Rosenblum Papers, Stanford University Special Collections.

In June 1981, Bruce had a formal meeting in New York with Bill Garth, Prescott Low, and his father Louis, to present his Sinotype III proposal. Bruce dressed for the part, arriving in a three-piece suit. In Bruce’s formal proposal, he cited a total of $7,500 in hardware costs, with an additional $5,000 for programming fees. The plan promised a Chinese word processor, running on an Apple II, delivered in approximately four months’ time. If this worked, it would reduce the cost of such a machine by an order of magnitude.

Bruce got the job and went on to program Sinotype III from June to November 1981, balancing time between this and his full-time job as a tour guide for the National Park Service at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. During daytime breaks he would write out assembly code by hand, transcribing it at night. When Labor Day in 1981 came, and Bruce’s tour guide job ended, he dedicated two months straight to finishing the code, and delivered it to GARF.

Memory hacking

The first problem that GARF and the Rosenblums faced was that of computer memory. Developers of early Chinese personal computers explored every available option in their effort to juice as much memory as possible out of their systems. We will explore two strategies in particular, sometimes employed in isolation, but often in concert: Adaptive Memory and Chinese Character Cards.

The Sinotype III system comprised five components: a Sanyo DM5012CM 12-inch monitor; an Epson MX-70 printer; a Corvus 10 MB “Rigid Disk Storage” for storing the Chinese character bitmap database and their corresponding “descriptor codes”; an Apple Disk Drive “for storage of text files”; and the Apple II itself.

Out of the box, the Apple II came with 32K of RAM, extensible to 48K on the motherboard. “We maxed that out even before the Apple II left the store,” Bruce Rosenblum remarked by email to me. 48K of memory was still far too little for his purposes, however, and so Bruce opted for what, at the time, was a fully standard modification, commonly employed by so-called “power users” of the era: namely, to insert an additional 16K memory card in Slot 0, thereby bringing the total available memory to 64K.

Even this was too little, however. “I needed more RAM to store a full encoding system,” he said, “and also the 16-by-16 bitmaps for the 100 most frequent ideographs.”

He began to explore a “mod” of the Apple II that few if any others had tried before. “Somehow,” he said, “I figured out I could put a second 16k board in slot 2 of the Apple II, and that gave me a total of 80k.” “Completely non-standard,” he continued, “but it worked with off-the-shelf components.”

This modification pushed the machine past its own limitations, however. The 6502 microprocessor on the Apple II was only capable of accessing 64K of memory directly—meaning that, even with the additional 16K Bruce had managed to bootstrap in with the second memory board, there was simply no built-in way for the Apple II to simultaneously access these additional addresses in memory. So “non-standard” was this mod that, when he told an Apple engineer about it during one of his many conversations, the Apple rep was shocked—he had never heard of, or thought of, doing such a thing.

To enable the Apple II to access 80K of memory, rather than just 64K, Bruce dispensed with the out-of-the-box operating system and programmed his own in assembly language. Key to his custom-designed program was the possibility of “selecting between two banks of 16K that overlap each other.” In other words, although only 64K worth of memory locations would be accessible at any one instant, by rapidly oscillating between the two memory expansion cards, he could in effect trick the computer into accessing both at speeds that, from the perspective of the user, would have been negligible. That squeezed 25 percent more memory out of the system, enabling the inclusion of perhaps as many as 400 more Chinese characters in on-board memory.

Bruce delivered the final code to GARF the week before Thanksgiving, and then set out on a world backpacking tour that would take him across Europe and Asia. From this point on, development of Sinotype III would be largely in the hands of Louis Rosenblum and GARF, although Bruce continued to serve as a consultant, exchanging frequent correspondence with his father from wherever in Europe, China, India, or elsewhere he found himself at the moment.

Speeding toward real-time Chinese typing

Even with his ingenious mod, however, Louis and Bruce estimated that a mere 600 to 1000 Chinese characters would be able to fit in on-board memory. When accounting for the size of Sinotype III’s operating system, program applications, and the memory requirements of each Chinese character, the vast majority of Chinese characters in the machine’s lexicon would need to be stored somewhere else, whether on floppy disks, an external hard drive, or via some other hardware solution.

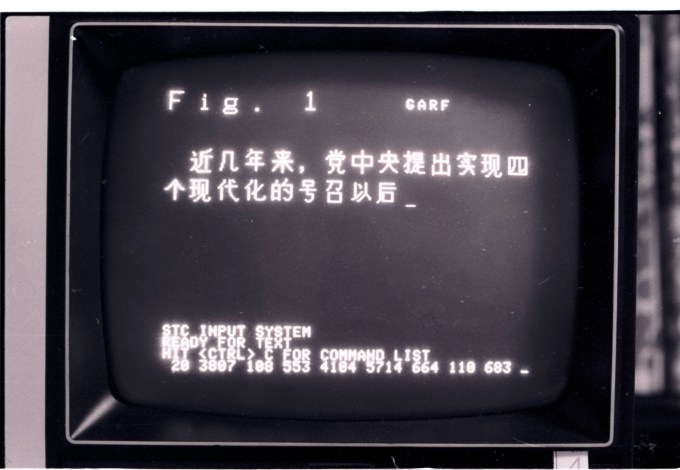

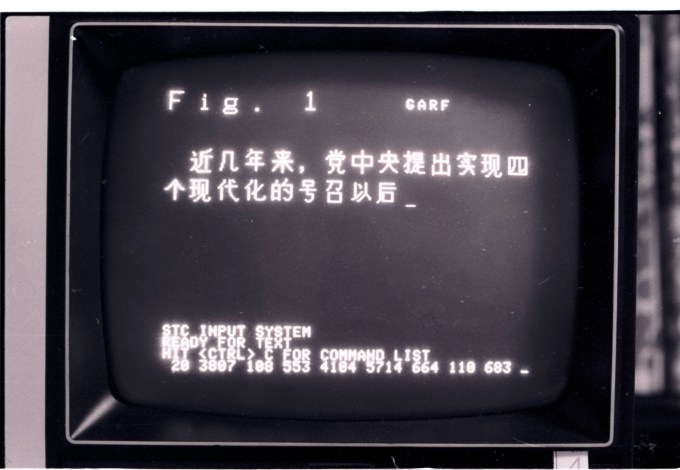

Sinotype III Computer Monitor. Courtesy of Louis Rosenblum Papers, Stanford University Special Collections.

Early on, Bruce briefly contemplated using PROM (Programmable Read-Only Memory) chips—but this idea quickly revealed itself to be a dead end. Circa 1981 and 1982, the largest PROM chips on the market maxed out at 2K of memory, which translated into a mere 28 to 51 Chinese characters. In order to store 7,000 Chinese characters in this fashion, then, Bruce would have needed either 138 or 250 PROM chips. “That’s a lot of chips,” he remarked.

Bruce then considered the possibility of storing characters on floppy disks. This, too, proved unworkable, not only because of the large number of disks it would have required, but also the slow access and retrieval speeds involved in fetching character bitmaps from floppy drive storage. GARF opted instead for a third solution: to outfit Sinotype III with an external hard drive, which at the time was an almost unheard-of microcomputer accessory. In order to overcome the profound memory limitations, GARF would store thousands of lower-frequency Chinese characters “off-site” in the system’s external hard drive: a 10 MB Corvus “Rigid Disk Storage.”

This had negative implications for the operating speed of Sinotype III, however. Within the space-time continuum of computing, in which most operations take place at blazing sub-second speeds, hard drives were cumbersome beasts. Particularly at this time, they relied on rigid magnetic disks—“platters”—that rotated within the device, not unlike a record player. The contents of various “tracks” were read by a head, similar to how the grooves on a record are read by the needle. Retrieval speeds depended upon the location of the head, and the particular rotational position of the disk at the moment of the retrieval request. Not unlike arriving at the stop to find that the bus has just departed, one had no option except to wait until the bus came back around again.

In concrete terms, retrieval times for Chinese characters stored on the hard drive were 10 times slower than those stored in RAM. Specifically, the retrieval time for those Chinese characters stored in RAM could be achieved in approximately 100 milliseconds per character—a unit of time imperceptible by human cognition. As for the characters stored in external storage, however, the input of any of these characters required as much as a full second to access and retrieve—a unit of time well within the threshold of human perception.

A one-second input time would have proven devastatingly slow within the context of mid-1980s personal computing, where users in English-language contexts were quickly becoming accustomed to real-time typing. In addition, one second is, obviously, ten times as long as 100 milliseconds, meaning that the average user would be able to feel this differential each and every time he or she wished to input lower-frequency characters.

In order to mitigate this problem, Louis Rosenblum hit upon an idea which he referred to as “adaptive temporary storage.” Sinotype III would be able to adjust the set of characters stored in RAM depending upon what the user had recently inputted. Upon initial boot, Sinotype III’s on-board RAM would be outfitted only with a predetermined set of high-frequency characters. The inputting of any hard-drive-based infrequent character would take up to one second, as noted above. However, “as each of the less frequent ideographs is keyboarded,” he explained in a letter at the time, “its code and dot matrix pattern will be noted in the random access memory.” In other words, such characters would be temporarily copied from the hard drive to on-board RAM cache, thereby reducing subsequent retrieval times.

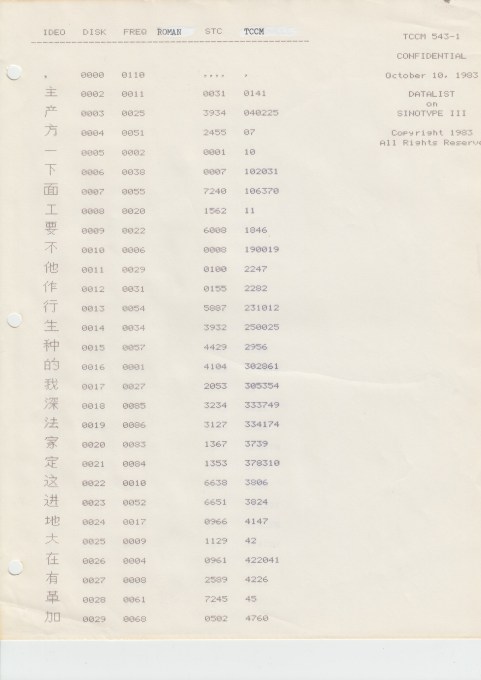

Internal GARF document showing Sinotype III character database and metadata. Courtesy of Louis Rosenblum Papers, Stanford University Special Collections.

Chinese-on-a-Chip

Even with recourse to toggling and adaptive memory, there remained many thousands of characters that fell beyond the limits of such strategies. While high-frequency Chinese characters accounted for a large percentage of overall usage, the production of any kind of technical or specialist content would have certainly brought the user repeatedly into the “off-site” repository of Chinese characters. More of these “low-frequency” characters needed to be brought “on-site” if the experience of Chinese computing was ever going to approach the same feeling of instantaneity enjoyed by English-language counterparts.

Engineers in the late 1970s and early 1980s began to explore a different hardware solution, referred to as “Chinese Character Cards” (Hanka), “Chinese Cards” (Zhongwenka), “Chinese Character Generators,” “Chinese Font Generators” (Hanzi zimo fashengqi) or, as one article delightfully referred to them, “Chinese-on-a-Chip.” Much like memory cards and graphic cards, “Chinese character cards” were designed to be installed directly into motherboard expansion slots. Hardwired into these cards were thousands of Chinese bitmaps and input encodings. In effect, they served the same role as an external hard drive, but at far faster speeds and with more reliable performance.

“Chinese-on-a-chip” cards were not the focus of research at GARF. Rather, they grew out of the earlier era of custom-designed Chinese systems, all prior to the personal computing revolution. These included systems such as the Ideographix IPX, by Chan Yeh, and the Olympia 1011, which were outfitted with microprocessors whose sole purpose was the generation of character bitmaps and the storage of input descriptors. On the Olympia 1011 Chinese word processor—basically a single-purpose electric Chinese typewriter—one of the three Intel 8085 processors was dedicated exclusively to Chinese character generation.

During the early 1980s, such character generators were commoditized and turned into saleable products themselves. No longer did one need to buy a full-fledged word processor, such as the Olympia 1011, to gain access to this kind of on-board character generator. Instead, one could purchase a “Chinese Character Card” and then install it on one’s personal computer of choice.

Among the earliest centers of Chinese computing to focus on Chinese Character Cards was Tsinghua University, where researchers developed an early card capable of storing approximately 6,000 Chinese bitmap patterns in 32-by-32 dot matrix format. By the mid- and late-1980s, there were dozens of different “Hanka” on the market, manufactured and marketed by companies across Japan, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, the United States and elsewhere.

By the mid- and late-1980s, the “Chinese-on-a-chip” approach became so important and common that practically all computers boasting Chinese or Japanese-language capabilities featured a character generator card of one sort or another.

Thus, from the 1950s with Caldwell’s Sinotype to the duo father-son Rosenblum team and GARF around Sinotype III in the 1980s, solving the memory problems associated with Chinese characters was the linchpin to opening the Chinese market to computing. Hacking computers with more memory, creating adaptive memory algorithms for prioritizing characters, and building dedicated hardware bridged the problem and initiated the computer revolution in China.

Yet, the next step was how to expand beyond the computer itself to everything that might connect to it. In part two of this series, coming up shortly on TechCrunch, our discussion will continue with a deep-dive into the challenges of designing and programming early computer monitors, printers, and other peripherals capable of handling Chinese text output.