Elon Musk joked earlier this month that he hoped buying Twitter won’t be too painful for him. But the self-proclaimed “free speech absolutist” may indeed be inviting a world of pain for himself (and his wallet) if he sets the platform on a collision course with the growing mass of legislation now being applied to social media services all around the world.

The US lags far behind regions like Europe when it comes to digital rule-making. So Musk may simply not have noticed that the bloc just agreed on the fine detail of the Digital Services Act (DSA): A major reboot of platform rules that’s intended to harmonize governance procedures to ensure the swift removal of illegal speech, including by dialling up fines on so-called “very large online platforms” (aka, VLOPs; a classification that will likely apply to Twitter) to 6% of global annual turnover.

On news of Musk’s winning bid for Twitter, EU lawmakers were swift to point out the hard limits coming down the pipe.

“The Commission can fine [non-compliant platforms] 6% of worldwide turnover,” emphasizes MEP Paul Tang, discussing why he believes the DSA will be able to rein in any more absolutist tendencies Musk may have.

“Given the profit margin currently for Twitter that is a lot — because the net profit margin in negative, that’s the reason why he bought it in the first place I assume… It doesn’t make a profit and if it makes a profit it will be chipped away by the penalty. So he really has to find ways to make it more profitable to make sure that the company doesn’t lose money.”

Tang also points out that Musk’s $43BN bid for Twitter is financed, in large part, with loans — rather than him just cashing in Tesla equity to fully fund the bid, which means Musk is not as free to act on his impulses as he may otherwise have been.

“He’s in debt. He needs to pay his debts — his creditors… If he’d used all his equity to buy Twitter then he would have had more leeway, in a sense. He could take any loss he wants — up to a point, depending on the value of Tesla. But he’s in debt now, in this construction, so at least he has to pay for the interest — so the company needs to make a profit. And even more than before, I think.”

“It’s 6% for every failure to comply. It would be an expensive hobby,” agrees MEP Alexandra Geese, dismissing the idea that the billionaire will just view any DSA fines as the equivalent of ‘parking tickets’ to be picked off and flicked away.

As well as headline fines of up to 6% for breaches of the regulation, repeated failures by a Musk-owned Twitter to comply with the DSA could lead to the European Commission issuing daily fines; suing him for non-compliance; or even ordering a regional block on the service.

Article 41(3) of the regulation sets out powers in the event of repeated, serious infringements which — per snippets of the final text (still pending publication) we’ve seen — include the ability to temporarily block access to a service for four weeks, with the further possibility that that temporary ban could be repeated for a set number of times and thus prolonged for months, plural.

So even if Musk’s fortune (and inclination) were to extend to regularly shelling out for very large fines (up to hundreds of millions of dollars on current Twitter revenue) he may have harder pause about taking a course of ‘free speech’ action that, de facto, limits Twitter’s reach by leading to the service being blocked across the EU — since he claims he’s buying it to defend it as an important speech forum for human “civilization”. (Assuming he’s not narrowly defining that to mean ‘in the U.S. of A.’.)

While the full spectrum of the DSA isn’t due to come into force until the start of 2024, rules for VLOPs have a shorter implementation period — of six months — so the regime will likely be up and running for platforms like Twitter in early 2023.

That means if Musk wants to — shall we say — ‘fuck around and find out’ how far he can push the needle on speech absolutism across the EU, he won’t have very long before the Commission and other regulators are empowered to come calling if/when he fails to meet their democratic standard. (In Germany, there are already laws in place for platforms: The country has been regulating hate speech takedowns on social media since 2017 — hence the ‘joke’ has long been that if you want a de-nazified version of Twitter you just change your country to ‘Germany’ in the settings and your Twitter feed will instantly become fascist-free.)

The DSA puts a number of specific obligations on VLOPs that may not exactly be front of mind for Musk as he celebrates an expensive new addition to his company portfolio (albeit, still pending shareholder approval) — including requiring platforms to carry out risk assessments related to the dissemination of illegal content; to consider any negative impacts on fundamental European rights such as privacy and freedom of expression; and look at risks of intentional manipulation of the service (such as election interference) — and then to act upon these assessments by putting in place “reasonable, effective and proportionate” measures to combat the specific systemic risks identified; all of which must be detailed in “comprehensive” yearly reports, among a slew of other requirements.

“An ‘Elonised’ version of Twitter would probably not meet the DSA requirements of articles 26-27,” predicts Mathias Vermeulen, public policy director at the digital rights agency AWO. “This can lead to fines (which Musk doesn’t care about), but it could lead to Twitter being banned in the EU in case of repeated violations. That’s when it really gets interesting: Would he change his ideal vision of Twitter to preserve the EU market? Or is he prepared to drop it because he didn’t buy this as a business opportunity but to ‘protect free speech in the US’?”

The UK, meanwhile — which now sits outside the bloc — has its own, bespoke ‘harms mitigating’ social media-focused legislation on the horizon. The Online Safety Bill now before the country’s parliament bakes in even higher fines (up to 10% of global turnover) and adds another type of penalty into the mix: The threat of jail time for named executives deemed to be failing to comply with regulatory procedures. (Or, put another way, trolling the regulator won’t be tolerated; they’re British… )

Is Musk willing to go to jail over a maximalist conception of free speech? Or would he just avoid ever visiting the UK again — and let his local Twitter execs do the time and take the lumps?

Even if he’s willing to let his staff languish in jail, the UK’s draft legislation also envisages the regulator being able to block non-compliant services in the market — so, again, if Musk kicks against local speech rules he’ll face trading off limits on speech on Twitter with limits on Twitter’s global reach.

“This is not a way to make money,” Musk said earlier this month of its bid for Twitter. “My strong intuitive sense it that having a public platform that is maximally trusted and broadly inclusive is extremely important to the future of civilization. I don’t care about the economics at all.”

“I think he doesn’t understand quite how big a fight he’s in for, nor how complex free speech is in practice. It’s going to be interesting to watch!” says Paul Bernal, a UK-based professor of IT law at the University of East Anglia. “The big risk (as ever) is that he fails to understand that his own experience of Twitter is very different from what happens to other people.”

Elsewhere, a growing number of countries are setting their own local restrictions and ramping up operational risks for owners of speech fencing platforms.

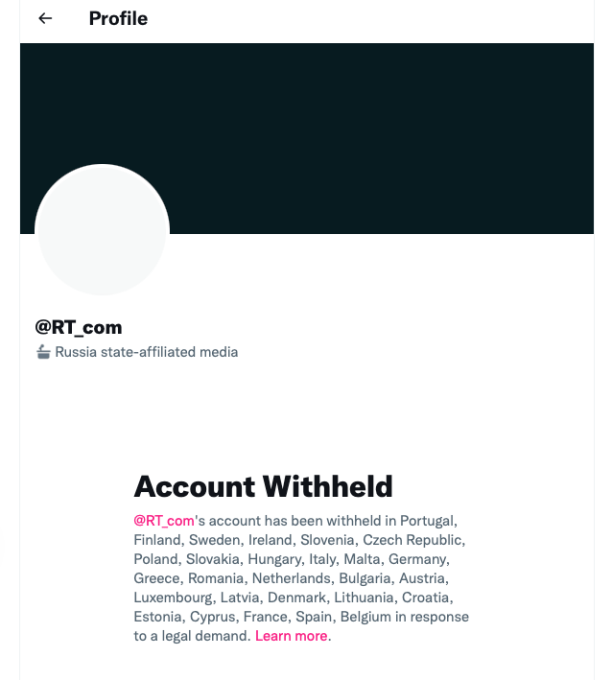

This includes a growing number of autocratic (or autocratically leaning) regimes that are actively taking steps to censor the Internet and restrict access to social media — countries such as Russia, Turkey, India or Nigeria — where platforms that are ‘non-compliant’ with state mandates may also face fines, service shut downs, police raids and threats of jail time for local execs.

“A platform might be able to get away with free-speech absolutism if it restricted its operations to the United States with its specific and peculiar first amendment tradition. But most platforms have 90% or more of their users outside the US, and a growing number of governments around the world, both democratic and less so, increasingly want to influence what people are and are not allowed to see online. This goes for the European Union. It clearly goes for China. It also goes for a number of other countries,” says Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, a professor of political communication and director at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford.

“Saying ‘I’m for free speech’ is at best a starting point for how private companies can respond to this. If you are rich enough, you can maybe soak up the fines some governments will impose on companies that in the name of free speech (or for other reasons) refuse to do as they are asked to. But in a growing number of cases the next steps include for example going after individual company employees (Indian police has raided local Twitter offices), forcing ISPs to throttle access to a platform (as Turkish government has done), or ultimately block it entirely (as Nigerian government has done).

“So while in the United States, a platform that conducts content moderation on the basis of simplistic slogans will primarily face the fact that free speech is more complicated and ambiguous in practice than it is in theory, and that both users and other customers like advertisers clearly see that and expect companies to manage that complexity as clearly, consistently, and transparently as possible, in the rest of the world every platform will — if it wants to do business — face the fact that governments increasingly want to influence who gets to say what, where, and when.

“And that they (at best through independent judiciary and independent regulators, at worst directly through the executive branch), not individual proprietors or private companies, will want to decide what should and should not be free speech.”

Nothing Musk has said or done suggests he has anything other than a US-centric understanding of ‘free speech’. And that he therefore has a limited understanding of the scope of speech restrictions that can, legally, apply to Twitter — depending on where in the world the service is being used. And the prospect of Musk owning Twitter can’t change any actual laws around speech — however much he makes striking statements equating his ownership to the ‘defence of human civilization’.

Away from the (relatively clearly defined) line of illegal speech, perhaps most obviously (and depressingly), Musk having an overly simplistic understanding of ‘free speech’ could doom Twitter users everywhere to a ‘Groundhog Day’ style repeat of earlier stumbles — when the company’s (US-centric) operators allowed the platform to steep in its worst users’ bile, professing themselves “the free speech wing of the free speech party” while victimized users were essentially censored by the loudest bullies.

It still feels like the very recent past (actually it was circa 2018!) when Twitter’s then CEO and co-founder, Jack Dorsey, appeared to have a micro epiphany about the need for Twitter to factor in “conversational health” if it wanted anyone other than nazis to stick around on its platform. That in turn led to a slow plod of progress by the company to tackle toxicity and improve tools for users to protect themselves from abuse. (And, very latently, to a ban on ‘king’ Twitter bully, Donald Trump.)

A free speech absolutist like Musk — who is expert at using Twitter to bully his own targets — threatens to burn all that hard won work right back down to ground zero.

But, of course, if he actually wants the world to want to hang out in his ‘town square’ and talk that would be the polar opposite of a smart strategy.

Musk may also try to turn his bullying on international regulators too, of course. He has (in)famously and publicly clashed with US oversight bodies — repeatedly trolling the SEC, via Twitter (ofc) — including tweeting veiled insults which pun on its three letter acronym. Or recently referring to it (or at least some of its California staff) as “those bastards”, in reference to an investigation it had instigated when he tweeted about wanting to take Tesla private.

Musk’s demonstrable rage and discomfort at the SEC’s perceived regulation of his own speech — and his open contempt for a public body whose job it is to police long-standing rules in areas like insider trading — doesn’t exactly bode well for him achieving friction-free relations with the long list of international oversight bodies poised to scrutinize his tenure at Twitter. And with whom he may soon be openly clashing on Twitter.

If he’s not yet taking tweet pot shots at these ‘bastards’ it’s likely because he doesn’t really know they exist yet — but that’s about to change. (After all, EU commissioners are already tweeting Musk to school him on how “quickly” he’ll “adapt” to their “rules”, as internal market commissioner Thierry Breton put it to “Mr Musk” earlier today… Touché!)

The Commission will be in charge of the oversight of VLOPs under the DSA once it’s in force — which means the EU’s executive body will be responsible for deciding whether larger platforms are in breach of the bloc’s governance structure for handling illegal speech, and, if so, for determining appropriate penalties or other measures to encourage them to reset their approach.

Asked whether it has any concerns with Musk owning Twitter — given his free speech “absolutist” agenda — the Commission declined to comment on Twitter’s ownership change, or any individual (and still ongoing) business transaction, but a spokesperson told us: “The Commission will keep monitoring developments as they take place to ensure that once DSA enters into force, Twitter, like all other online platforms concerned will follow the rules.”

What does Musk want to do with Twitter?

Musk hasn’t put a whole lot of meat on the bones of exactly what he plans to do with Twitter — beyond broad brush strokes of taking the company private — and claiming his leadership will unlock its “tremendous potential”.

What he has said so far has focused in a few areas — freedom of expression being his seeming chief concern.

Indeed, the first two words of his emoji-laden victory tweet on having his bid to buy Twitter accepted are literally “free speech”.

Though he also listed a few feature ideas, saying for example that he wants to open source Twitter’s algorithms “to increase trust”. He also made “defeating spam bots” part of his mission statement — which may or may not explain another reference in the tweet to “authenticating all humans” (which has privacy advocates understandably concerned).

In a TED interview earlier this month, before the sale deal had been sealed, Musk also responded to the question of why he wanted to buy Twitter by saying: “I think it’s very important for there to be an inclusive arena for free speech”.

He further dubbed the platform a “de facto town square”.

“It’s just really important that people have both the reality and the perception that they are able to speak freely within the bounds of the law,” Musk went on. “One of the things I believe Twitter should do is open source the algorithm. And make any changes to people’s tweets — if they’re emphasized or deemphasized — that action should be made apparent so anyone can see that that action’s been taken. There’s no ‘behind the scenes’ manipulation, either algorithmically or manually.”

“It’s important to the function of democracy, it’s important to the function of the United States as a free country — and many other countries — and actually to help freedom in the world more broadly than the US,” he added. “And so I think the civilizational risk is decreased the more we can increase the trust of Twitter as a public platform and so I do think this will be somewhat painful.”

What Musk means by freedom of speech is more fuzzy, of course. He was directly pressed in the TED interview on what his self-claimed “absolutist” free speech position would mean for content moderation on Twitter — with the questioner asking a version of whether it might, for example, mean hateful tweets must flow?

“Obviously Twitter or any forum is bound by the laws of any country it operates in so obviously there are some limitations on free speech in the US and of course Twitter would have to abide by those rules,” Musk responded, sounding rather more measured than his ebullient, shitposting Twitter persona typically comes across (which neatly illustrates the tonal dilemma of digital vs in person speech; which is to say that something said in person, with all the associated vocal emotion, body language and physical human presence, may sound very different when texted and amplified to (potentially) a global audience of millions+ by algorithms that don’t understand human nuance and are great at trampling on context).

“In my view, Twitter should match the laws of the country and really there’s an obligation to do that,” he also said, before circling back to what appears to be his particular beef vis-a-vis the topic of social media ‘censorship’: Invisible algorithmic amplification and/or shadowbanning — aka, proprietary AIs that affect freedom of reach and are not open to external review.

On this topic he may actually find fellow feeling with regulators and lawmakers in Europe — given that the just-agreed DSA requires VLOPs to provide users with “clear, accessible and easily comprehensible” information on the “main parameters” of content ranking systems (the regulation refers to these as “recommender systems”).

The legislation also requires VLOPs to give users some controls over how these ranking and sifting AIs function — in order that users can change the outputs they see, and choose not to receive a content feed that’s based on profiling, for example.

And Musk’s sketched vision of ‘putting Twitter’s AIs on Github’ for nerds to tinker with is, kinda, a tech head’s version of that.

“Having it be unclear who’s making what changes to where; having tweets mysteriously be promoted and demoted with no insight into what’s going on; having a blackbox algorithm promote some things and not other things. I think this can be quite dangerous,” he said in the TED interview, hinting that his time at Twitter might pay rather more attention to algorithmic content-disseminating apparatus — how the platform does or does not create ‘freedom of reach’ — than excessively concerning himself with maximizing the extremis of expression that can be contained within a single tweet.

So there are, on the surface, some striking — and perhaps surprising — similarities of thought in Musk’s stated concerns and EU lawmakers’ focus in the DSA.

He did also say he would probably want to set guidance that would prefer to keep speech up than take it down when expression falls in a grey area between legal and illegal speech — which is where the danger lies, potentially setting up a dynamic that could see Musk give a free pass to plenty of horribly abusive trolling, damaging conspiracy theories and outright disinformation. And that, in turn, could put him back on a collision course with European regulators.

But he also sounded fairly thoughtful on this — suggesting dialling back algorithmic amplification could be an appropriate measure in grey area situations where there is “a lot of controversy”. Which seems quite far from absolutist.

“I think we would want to err on the side of if in doubt, let the speech exist. If it’s a grey area I would say let the tweet exist but obviously in a case where there’s perhaps a lot of controversy you would not want to necessarily promote that tweet,” he suggested. “I’m not saying that I have all the answers here but I do think that we want to be very reluctant to delete things and just be very cautious with permanent bans. Time outs I think are better that permanent bans.”

“It won’t be perfect but I think we just want to have the perception and reality that speech is a free as reasonably possible,” Musk also said, sketching a position that may amount to the equivalent of ‘freedom of speech is not the same as freedom of reach’ (so sure the hateful tweet can stay up but that doesn’t mean the AI will give it any legs). “A good sign as to whether there’s free speech is, is someone you don’t like allowed to say something you don’t like. And if that is the case then we have free speech,” he added.

On the content side, the EU’s incoming regulation mainly concerns itself with harmonizing procedures for tackling explicitly illegal speech — it avoids setting prescriptive obligations for fuzzier ‘perhaps harmful but not literally illegal’ speech, such as disinformation, as regional lawmakers are very wary of being accused of speech policing.

Instead, the bloc has decided to rely on other mechanisms for tackling harms like disinformation — such as a beefed up but still non-legally binding code of practice — where platform signatories agree to “obligations and accountability” but won’t face set penalties, beyond the risk of public naming and shaming if they fail to live up to their claims.

So if Musk does decide to let a tsunami of disinformation rip across Twitter in Europe the DSA may not, on paper, be able to do much about it.

Geese agrees this is a “more complicated” area for EU regulation to tackle. But she notes that VLOPs would still have to do the risk assessments, be subject to independent scrutiny and audits, and provide researchers with access to platform data in order that they can study impacts of disinformation — which creates an investigative surface area where it becomes increasingly hard for platforms not to respond constructively to studied instances of societal harm.

“My guess would be if Twitter goes bananas the interesting European people would leave,” she also suggests. “It would lose influence if its seen as a disinformation platform. But the risk is real.”

“Do you really think that his defence of free speech is including the dissemination of disinformation,” wonders Tang of Musk’s speech position vis-a-vis unfettered amplification of conspiracy theories etc. “I’m not sure on that. I think he’s been — what I have seen — pretty faint or not explicit about it, at least… On dissemination he’s not very clear.”

Tang predicts that if Musk goes ahead with his idea of open sourcing Twitter’s algorithms it could be helpful by showing that Twitter “like other platforms, is basically built on trying to get disagreement because this is what people react to” — giving more evidence to the case for reforming how content gets algorithmically disseminated. “In that sense — that part of the plan — I think is good, or at least interesting,” he suggests.

Another stated “top priority” for Musk — a pledge to kill off the Twitter spambots — looks positive in theory (no one likes spam and a defence of spam on speech grounds is tenuous) but the main question here is what exactly will be his method of execution? His reference to “authenticating all humans” looks worrying, as it would obviously be hugely damaging to Twitter as a platform for free expression if he means he will impose a real names policy and/or require identity authentication simply to have an account.

But, discussing this, Bernal wonders if Musk might not have a more tech-focused feature in mind for slaying spam that could also lead to a positive outcome. “Does he mean real names and verified information, or does he mean using AI to detect bot-like behaviour? If he means real names, he’ll be massively damaging Twitter, without even realising what he’s doing. If he means using AI to detect bots, it could actually be a good thing,” he suggests.

The suspicion has long been that Twitter has never really wanted to kill off the spambots. Because identifying and purging all those fake accounts would decimate its user numbers and destroy shareholder value. But if Musk takes the company private and literally doesn’t care about Twitter’s economics he may actually be in a position to hit the spambot kill switch.

If that’s his plan, Musk would, once again, be closer to the EU’s vision of platform regulation that he might imagine: The bloc has been trying to get platforms to agree to identify bots as part of a strategy to tackle disinformation since its first tentative Code of Practice back in 2018.

Dorsey talked around the topic. How funny would it be if it takes Musk buying Twitter to actually get that done?

But what about an edit button? Every (sane) person thinks that’s a terrible idea. But Musk has repeatedly said it’s coming if he succeeds in owning Twitter.

Asked about it at TED earlier this month — and specifically about the risk of an edit button creating a new vector for disinformation by letting people maliciously change the meaning of their tweets after the fact — Musk managed to sound surprisingly measured and thoughtful there too: “You’d only have the edit capability for a short period of time — and probably the thing to do upon re-edit would be to zero out all retweets and favorites. I’m open to ideas though.”

So, well, maybe Musk was trolling everyone about being “absolutist” all along.

Yesss!!!

Yesss!!!

STATEMENT

STATEMENT