In my previous essay on TechCrunch, I examined the profound challenges which confronted the computer engineers trying to fit tens of thousands of Chinese characters in a memory system designed to handle a much smaller alphanumeric symbolic system.

Now, I turn to the question of Chinese character output—monitors, printers, and related peripherals—where still more challenges confronted engineers seeking to render Western-manufactured personal computers and computer peripherals compatible with Chinese character text.

While we call them “peripherals,” suggesting a sort of supporting role, they are in fact at the very center of computing in Chinese, from the extreme limitations that Chinese computing faced in the 1970s and 80s to the immense strides and successes it has experienced from the 1990s onward.

During the early rise of consumer PCs in the 1980s, no Western-manufactured personal computer, printer, monitor, operating system, or other peripheral was capable of handling Chinese character input or output—not “out of the box,” at least. To the contrary, all of these devices exhibited the same kind of English-language and Latin alphabetic bias found in, for example, the early history of telegraphic codes and mechanical typewriters, as I’ve explored in my other research.

During the 1980s, what ensued in China and the Chinese-speaking world was a period of intense hacking and modding. Element by element, engineers in China and elsewhere rendered Western-manufactured computing hardware and software compatible with Chinese. It was a messy, decentralized, and often brilliant period of experimentation and innovation.

When we turn our attention to this broader ecology of computing—on printers, monitors, and all of the other “stuff” needed to make computing work—part two of this series on Chinese computing spotlights two conclusions.

First, the dominance of alphabet-based computing—“alphabetic order,” as I call it—went far beyond the question of keyboards and computer memory. Like the typewriter before them, computing devices, languages, and protocols were by and large invented first in English-language contexts, and only later “extended” to other languages and to writing systems other than the Latin alphabet. To achieve even basic functionality, Chinese engineers needed to constantly push against the boundaries of off-the-shelf computing peripherals, hardware, and software.

Second, I’ll dismantle the oversimplified idea of Chinese “copycatting” and “piracy” that has dominated, then as now, Western accounts of Chinese computing during this pivotal period in the late 1970s and 1980s. When encountering programs such as “Chinese DOS,” the knee-jerk reaction in the Western world has been to treat them as just more “Chinese knock-offs.” What this simplistic narrative fails to understand is that without the kinds of “forgeries” we will examine in this article, none of these Western-designed software suites would have worked at all in the context of Chinese character computing.

Dot-matrix printing and the metallurgical depths of alphabetic order

The first peripheral we need to examine is the printer—specifically, dot-matrix printers. From the standpoint of Chinese computing, the politics of dot-matrix printing began with the then-dominant configurations of industry standard printer heads—the 9-pin printer heads found in practically all mass-manufactured dot-matrix printers during the 1970s.

These commercial dot-matrix printers were able to produce low-resolution Latin alphabet bitmaps with just one pass of the printer head. This was not by accident, of course. Rather, the choice of nine pins was “tuned” to the needs of low-resolution Latin alphabetic printing.

The same printer heads, however, were incapable of printing low-resolution Chinese character bitmaps in anything less than two full passes of the printer head. Two-pass printing dramatically increased the time needed to print Chinese as compared to English and also introduced graphical inaccuracies, whether due to inconsistencies in the advancement of the platen, uneven ink registration, paper jams, or otherwise.

Aesthetically, two-pass printing could also result in characters with differing ink densities on their upper versus their lower halves. Worse, in the absence of any mod, all Chinese characters would be at least twice the height of English words, no matter the font size being used. This created comically distorted printouts in which English words appeared austere and economical, while Chinese characters appeared grotesquely oversized. Such print-outs also wasted large amounts of paper, with every document looking something like a large-print children’s book.

An example illustration of how these printer heads work is provided in this video, courtesy of the author:

Latin alphabet-centrism ran deeper than one might initially expect, moreover, as illustrated in the work of early Chinese computing pioneer Chan Yeh. Setting out to digitize Chinese characters and basing his system on a bitmap grid of 18-by-22, Yeh’s initial idea was an obvious one: to reduce the diameter of the pins so as to fit more of them on the printer head. As he discovered, however, the solution would not be so simple.

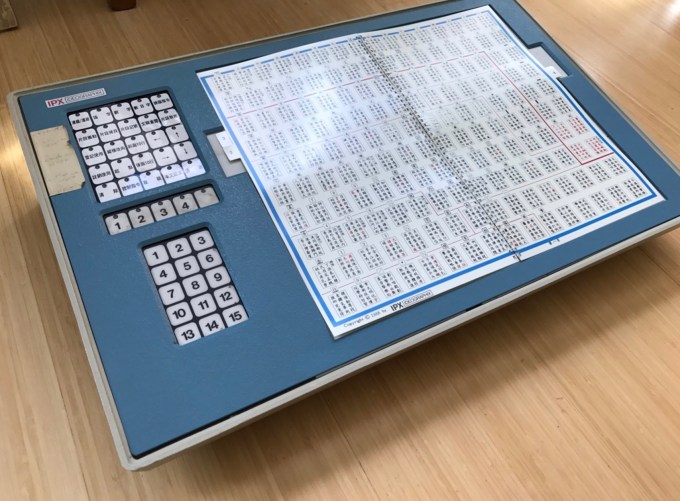

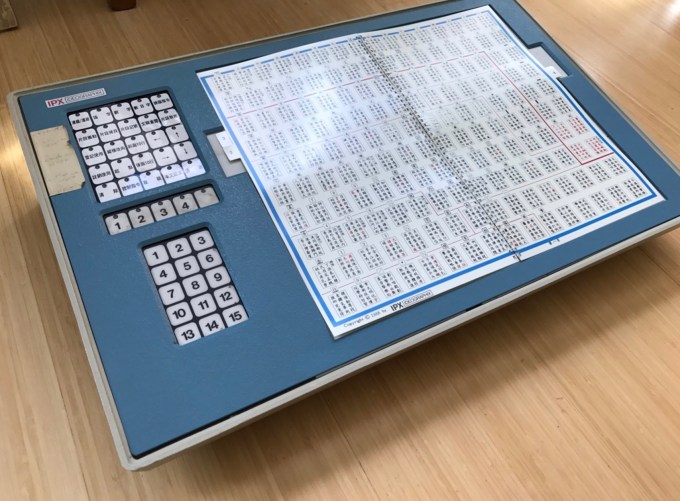

Interface of the IPX machine, invented by Chan Yeh and the Ideographix Corporation. Image Credits: Thomas S. Mullaney East Asian Information Technology History Collection, Stanford University

The Latin alphabetic bias of impact printing, he found, was encoded within the very metallurgical properties of printer components. Simply put, the metal alloys used to fabricate printer pins were themselves calibrated to 9-pin Latin alphabetic printing, such that reducing their diameters to the sizes needed for Chinese would result in pin deformation or breakage.

To compensate, engineers tricked Western-built printers into fitting as many as 18 dots in roughly the same amount of vertical space as nine normally spaced dots.

Their technique was ingenious and simple. Following standard, two-pass printing, an initial array of dots was laid down during the first pass of the printing head. Rather than laying down this second array of dots beneath the first, however, they tricked the printer into registering them in between the first set of nine dots, almost like the teeth of a zipper fastening together.

To achieve this effect, engineers rewrote printer drivers to hack the printer’s paper advance mechanism, refining it so that it rotated at an extremely small interval (as small as 1/216th of an inch).

Pin configurations weren’t the only challenge. Commercially produced dot-matrix printers were also tuned to the ASCII character encoding system, and thus unable to handle Chinese text as text. In English-language word processing, printing was not an act of transmitting a raster image to the printer. Rather, English-language text could be directly delivered via the printer driver as ASCII-encoded text, which resulted in much faster printer speeds.

In order for Western-built dot-matrix printers to print Chinese characters, however, there was no way to use these printers’ “text” mode. Instead, the printers once again had to be tricked, this time in order to print Chinese characters using the graphics mode typically reserved for printing raster images.

For students of the Chinese language, the irony here will be apparent: in order for Chinese characters to function on early Western-built dot-matrix printers, Chinese characters had to treated as pictures or pictographs. Pictographs were something that Westerners had long assumed Chinese characters to be, even though they are not (with few exceptions). But in the context of dot-matrix printing, “pictographs” were indeed what they had no choice but to become.

Eventually, a new family of impact printers began to be released on the commercial market: 24-pin dot-matrix printers, featuring pin diameters of 0.2 mm (as compared to 0.34mm on 9-pin printers). Unsurprisingly, the leading manufacturers of these new printers were largely Japanese companies such as Panasonic, NEC, Toshiba, Okidata, and more. Given the need to print characters required by the Japanese language, Japanese engineers needed to solve similar challenges as their Chinese counterparts.

Pop-up modernity: Chinese character monitors

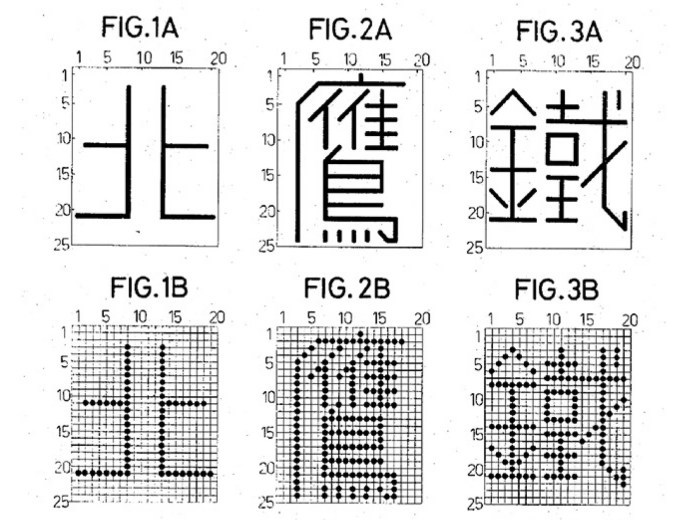

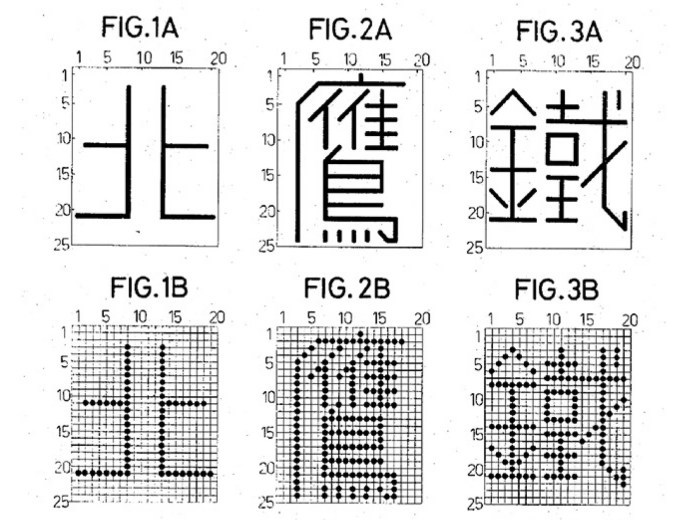

Patent document image demonstrating the conversion of Chinese characters into bitmap rasters. Image Credits: Thomas S. Mullaney East Asian Information Technology History Collection, Stanford University

Yet another domain within the ecology of Chinese computing was that of mass-manufactured computer monitors. In certain respects, the politics of monitors were similar to those of printers, particularly with regards to the issue of character distortion. Unavoidably, even the lowest-resolution Chinese character bitmaps occupied upwards of twice the vertical and horizontal space of Latin alphabetic letters, making the Chinese in bilingual texts appear comically oversized (such as can be seen in this story’s featured image).

Standard, Western-manufactured computer monitors could also fit a far smaller number of Chinese characters on screen than Latin letters, both in terms of line length (the number of characters per line) and depth (the number of lines per screen). Chinese language users could thus see only small portions of their texts at any one time.

Then there were challenges unique to Chinese character display: the pop-up menu. Because of the inherently iterative process of Chinese input, in which users are constantly being presented with Chinese characters that fulfill the criteria provided by their keystrokes, an essential feature of Chinese computing is a “window”—whether software-based or hardware-based—that enables the user to review these Chinese character candidates.

Although the pop-up menu is a ubiquitous feature of Chinese computing from the 1980s onward, this feedback technique dates back to the 1940s. In a 1947 experimental Chinese typewriter designed by Lin Yutang, there was a key component of the machine the inventor called his “Magic Eye”: in effect, the first “pop-up menu” in history, albeit a mechanical one.

With the advent of personal computers, mechanical windows such as those found on the MingKwai, Sinotype, Sinowriter, or otherwise, were integrated into the computer’s main display. It became a software-governed “window” (or bar) on the screen, rather than a separate, physical device.

This pop-up menu placed further constraints on the already precious real estate of the computer monitor, however. What we might term “pop-up menu design” became a critically important area of research and innovation within Chinese personal computing from its inception. Companies experimented with different menu styles, formats, and behaviors, attempting to strike a balance between the requirements of input, screen size, and the preferences of users.

There were trade-offs to each option. Menus that displayed a larger number of character candidates at once increased the likelihood of more rapidly finding one’s desired graph, but came at the cost of screen space. Smaller windows, while less intrusive, required the user to scroll through “pages” of character candidates, if the user’s desired graph was not found amongst the top recommendations.

As a consequence of these strict limitations, Chinese engineers and firms were constantly seeking next-generation monitors. While this was perhaps true for the global market at large—since higher resolution monitors represent something of an “inherent good” for consumers—nevertheless, the motivating reasons for this hunger for high-resolution was dramatically different for the Chinese-language market.

Conclusion: No ESC

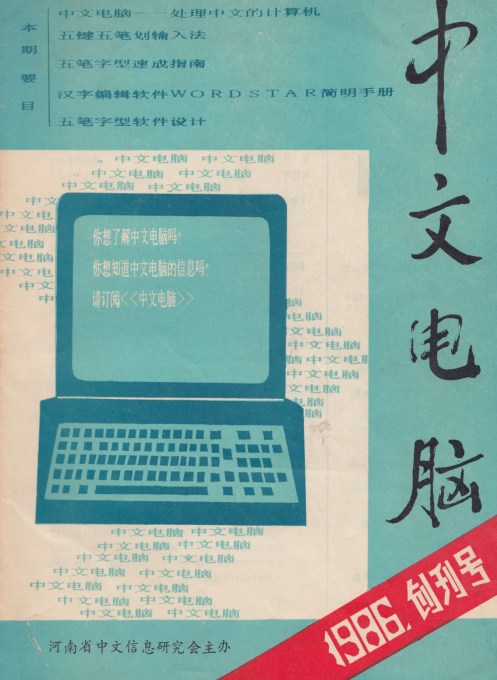

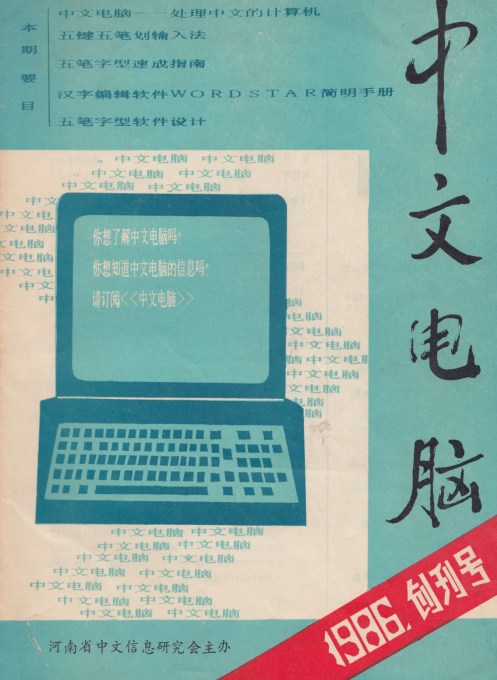

Inaugural issue of the magazine “Chinese Computing”. Image Credits: Thomas S. Mullaney East Asian Information Technology History Collection, Stanford University

As brilliant as each of these mods might have been, at the end of the day they remained just that: modifications. The autonomy and authority to create original systems—that is, the systems that subsequently needed to be modified—was ultimately where power was concentrated.

While the practice of modding tended to lead to a wide array of systems, it often came at the expense of interoperability. Modding required constant vigilance, moreover—no one-time “set it and forget it” solution was possible.

With every new computer program released on the market—and every new version of every computer program—programmers in China had to “debug” them line by line, insofar as programs themselves contained code which could set, or reset, parameters for the computer monitor, for example.

For most English-language word processing programs, for example, the baseline assumption baked into such programs was a 25-by-80 character display format (zifu fangshi xianshi). Since this format was incompatible with Chinese character display, engineers had to manually change every place in the program code where this 25-by-80 format was set. They did so, tellingly enough, using standard-issue “DEBUG” software. Through accumulated experience, engineers steadily learned their way around the assembly code bowels of leading programs.

Once modded, moreover, underlying operating systems and programs could always change. Shortly after the development of CCDOS and other systems, for example, IBM announced its move to a new operating system: the PS/2. “China and Chinese-language have been thrown into turmoil,” one article from 1987 wrote, noting that no existing Chinese-language systems—whether in Taiwan or on the mainland—had yet to be adapted to it. “The race is on for developers to come up with the best match for IBM’s MS/DOS platform.”

From an historical perspective, modders are vulnerable to misrecognition and erasure. In their time and place, their work was often misrecognized as mere theft or piracy, rather than as necessary acts of re-engineering to render incompatible machines compatible with the Chinese language. In a January 1987 issue of PC Magazine, for example, one cartoonist lampooned Sinicized operating systems. “It Runs on MSG-DOS,” the cartoon’s caption read.

As Western manufacturers slowly incorporated many of these Chinese mods into the core architectures of their systems (as well as Japanese and other non-Western ones), it is all too easy to forget that such changes were inspired by the work of engineers in China and the non-Western world. In sum, it is all too easy to retroactively imagine that the Western-built computer has always been language-agnostic, neutral, and welcoming.

This critical period of computing history has gone completely unwritten, and for a very simple reason. In the United States, and the Western world more broadly, none of these mods have been understood in terms of “experimentation,” let alone “innovation.” Instead, another set of words was—and continues to be—reserved for them: “copycatting,” “mimickry,” “piracy.” As Chinese engineers reverse-engineered Western-built dot-matrix printers, enabling them to print Chinese characters; or retrofitted Western-designed operating systems to make possible the use of Chinese input method editors, all that most Western observers could see was “theft.”