Gamification and social hooks have become cornerstones across every category of consumer apps these days, and today one that’s using these to build out a new e-commerce platform is Europe is announcing a seed round to give its growth a boost. Blidz — a social shopping app that offers big discounts (many items in categories like jewelry, clothes and gadgets sell for just $0.99 on there) on goods based on how many people are coming together to buy them, and then presents users with a selection of games on top of that to unlock more deals — has picked up €6 million ($6.6 million at today’s rates) in a seed round of funding after seeing its early growth reach 50,000 monthly users.

General Catalyst — one of the group of VCs out of the U.S. that have turned increasing attention to backing startups out of Europe in recent years — and European VC Peak are co-leading this round, with D4 Ventures, Fabric Ventures, FJ Labs and previous backer IPR.VC also participating, along with a few individuals: Youngme Moon (the Harvard professor who focuses on the digital economy), Christopher North (formerly a longtime Amazon exec, now primarily an investor) and Don Hoang (the ex-Uber and Revout exec).

If you are au fait with the world of social shopping and the description of Blidz sounds a little familiar to you, it might be because it is in large part a clone, specifically of Pinduoduo, the wildly successful gamified social shopping app in China, which CEO Lasse Diercks, who co-founded Blidz with Markus Haverinen (CPTO), cites as a direct inspiration.

“We saw the trend of Pinduoduo, learned how the model worked, built it and sent it out to the market a little over a year ago,” he told me matter-of-factly in an interview the other day.

Pinduoduo’s fortunes and challenges are bookends worth contemplating with thinking about Blidz: the Chinese platform currently has a market cap of nearly $60 billion (it’s listed on Nasdaq in the U.S.) and nearly 870 million active buyers — although recent growth has been slowing on the back of more competition and the weaker performance of China’s economy overall. That speaks of a lot of potential for Blidz, but also some of the same growth issues longer term.

The longer-term challenges, however, seem to be a far-off consideration at the moment for a startup that is only a year old. Like Pinduoduo’s founder Colin Huang, Diercks tells me he saw an opportunity to provide a different offering to the market beyond the domination not just of Amazon but the Amazon approach to e-commerce that was essentially being repeated by other marketplace platforms (build for scale with a huge number of SKUs, optimize around personalization, search and ads to surface products to potential buyers, improve margins by providing your own products alongside these and/or other logistics economies of scale).

“Our vision is to liberate Western consumers,” Diercks said. “We want to offer the western consumers better and less expensive shopping experience.”

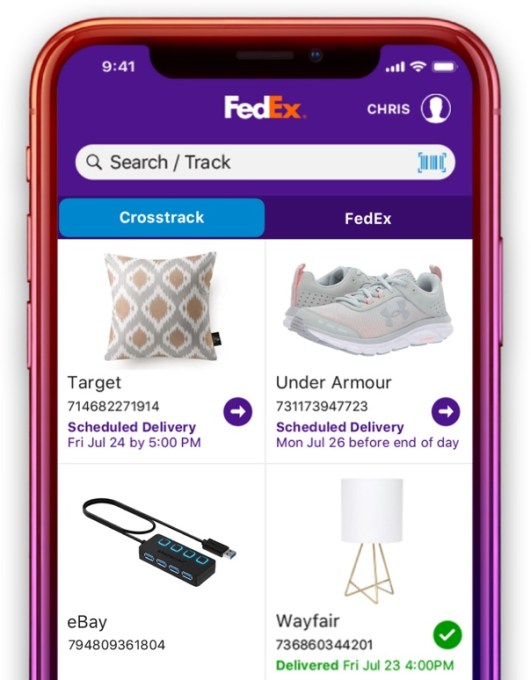

In his view, that offering is addressed in two ways. Firstly, it’s about the front-end experience. Using gamification (currently there are four games on Blidz, and there will be more coming), Blidz also uses social hooks (share your deal on your timelines and in messaging to friends and groups!) respectively to engage users, getting them to create their own network effect by recommending products to people they know over other social channels, and for people to be won over to buying goods by seeing how many others are also buying them, and the price lowering as a result.

(That indeed has been a trick used in the pre-internet days, too, initially pioneered by home shopping live TV shows where people phoned in to buy goods.)

Secondly is the choice that Blidz, like Pinduoduo before it, is making to accept a much lower margin on sales in exchange for selling more goods.

Translating that to today’s internet landscape in regions like Europe and the U.S. was a no-brainer since the market has so little variety in it at the moment.

“Sixty percent of e-commerce in Europe today is dominated by Amazon, and then a long tail of others like it. We believe that there is a monopoly in price extraction,” he said. “In the end, that’s the vision of the company, to offer Western consumers a better and less expensive shopping experience.”

The solution, he believes, is to accept a much smaller margin on goods sold and aim for simply selling more of them to make up the difference and then some. China’s Pinduoduo, he said, sometimes makes as little as 0.5% off a sale. “This is a 60x difference compared to for example Wish.”

China is playing another key role for the company beyond being the market that birthed the platform that is Blidz’s inspiration: it’s also the key country in the supply chain for goods that are sold on Blidz. That’s reality commerce for you: although there are definitely signs of some startups building business models that nurture more manufacturing and goods production closer to those who are making purchases, China remains a critical supplier for the wider consumer market, and will be for a long time.

“We are building a supply chain in China where we have a team ex-Wish guys. They are building this for us,” said Diercks. This is not about buying cheap goods, but tapping into a newer generation of products coming out the country’s factories that are just as good and sometimes better than the average offerings. It then buys these in bulk, in a concept he described as “quality-to-price.”

“We don’t want to work with every supplier. We want to work with a select number,” he said. And that constrain of supply appears to be giving Blidz better bargaining power, he said. “They are waiting to come on board. The end vision is to be the Shein of this space,” he added, referring to the Chinese fashion sensation that has leveraged its own direct relationships with clothes and accessory manufacturers to source a higher level of quality, and then sells those goods directly to consumers itself.

The social shopping space is littered with a lot of businesses that appeared to be rocket ships, only to fizzle out their engines before reaching long-term, stratospheric orbits. Diercks doesn’t believe that Pinduoduo, and now Blidz, are comparable to these. “We don’t believe that Groupon or LivingSocial were ever really that social,” he said, because they never truly leveraged people’s own social graphs in their selling approaches. They are also more focused on experiences rather than products in their DNA, even if more recently Groupon’s goods business has shifted that somewhat.

The potential here of building out that model to more markets and possibly picking up more localized variations along the way, and picking up what looks like a base of loyal users up to now, have together been enough to sell the idea to top investors willing to take a punt on it.

“The Blidz founding team has a number of unique insights relating to the evolution of online commerce,” noted Adam Valkin, MD of General Catalyst, in a statement. They are creating a new customer experience in the West by combining social media, gaming and shopping into a data-driven entertaining and easy-to-use platform. We’re excited to see what emerges from this talented team.”