It’s my last day of work for the year, so we’re going to have some fun. Obviously, we’re talking crypto this morning.

Jack Dorsey, former Twitter CEO and present CEO of Block, the company formerly known as Square, stirred the crypto pot recently, making explicit his preferences in the larger blockchain landscape by taking swipes at decentralized internet projects that don’t fall under Bitcoin’s aegis.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

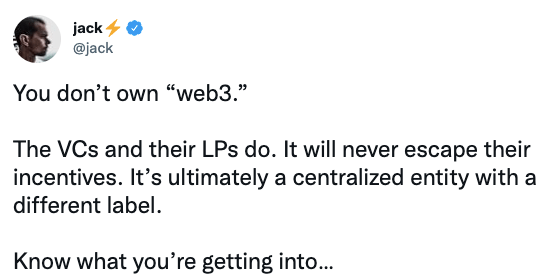

To avoid being accused of misinterpreting Jack, here are his key statements, starting with the genesis tweet of the conversation:

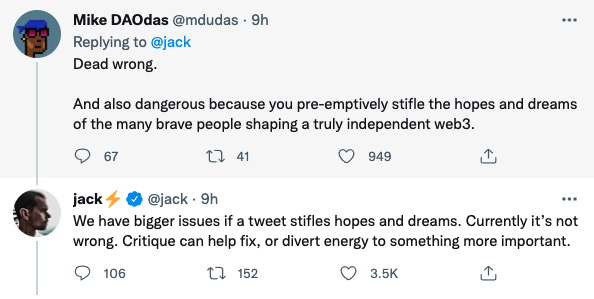

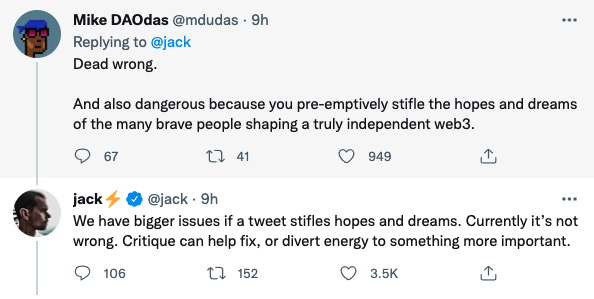

Which went down like a party foul with well-known web3 stans:

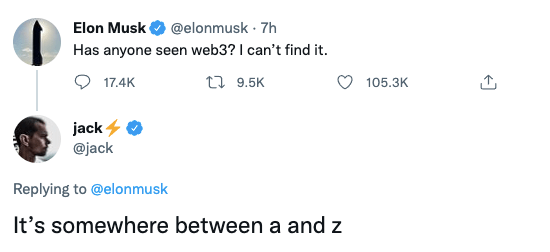

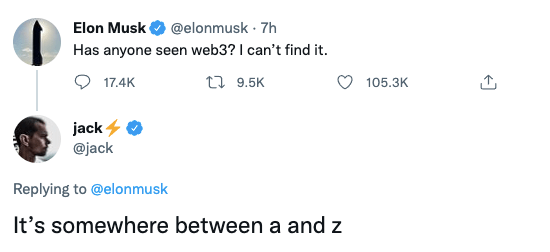

And a few hours after Jack’s tweet, Elon Musk joined in the fun:

There are several different things being said here, and a few of the tweets could use a bit of explaining if you don’t live on Twitter. The Exchange has your back:

- On who “owns” web3: Jack argues that regular users aren’t owners of web3 projects. Instead, the CEO claims that venture capitalists and, in turn, their investors are. Even more, Jack doesn’t expect this dynamic to change; instead, he anticipates that centralized capital pools backing a plethora of crypto projects will maintain quite a lot of control thanks to venture incentives.

- On being critical of web3: After being criticized for “stifling” web3 work, Jack dismissed the complaint and said that “critiques” can help folks choose to work on more fulfilling projects.

- On who will own web3: Elon Musk jumped into the fun to ask where web3 is, as he is struggling to find it. Jack then subtweets a16z, the venture capital firm, as the nexus point for web3 project funding, and therefore control.

What matters in the above is that Jack, a well-known proponent of the original cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, isn’t big on web3 projects.

It’s notable that these two characters popped up to argue against the flood of greed that’s cropped up in the decentralized economy over the last few years, with every traditional pile of money wanting to get in on putative web3 returns.

Who owns what?

The core of Jack’s complaint is that leading web3 corporations are owned by venture capitalists, and therefore will have to live with venture incentives.

“Venture incentives,” of course, is a polite way of saying running a company in such a manner that venture capitalists and their backers make lots of money.

The complaint is pretty true. Venture capitalists invested more than $6 billion into crypto projects in Q3 2021 alone. That should give you an idea of the scale of the crypto world being purchased by traditional, private-market investors at the moment. More simply, pension funds own a lot of the crypto economy.

Jack’s diss about venture capitalists and web3 didn’t stop there. Not only did Jack say that web3 projects have a weakness in their core thanks to the economic bargains their progenitors have made with external capital, but also that they are centralized.

Aside from calling someone a “nocoiner” who is going to, alternatively, “stay poor” or “ngmi,” saying that a crypto project is centralized is perhaps the rudest possible comment.

Is Jack wrong? No, he is not.

It is true that venture players are flooding the zone in web3 with cash and assistance because they think it will make them money. This leads to quite a lot of centralization. For example, I find it blisteringly funny that a16z is an investor in both Coinbase and OpenSea. And that Coinbase intends to get in on the NFT game. You know, the thing that OpenSea currently rules.

Even more, projects like Solana sold a bunch of their tokens for a song to venture investors, effectively handing out upside that is forever frozen in already swollen accounts. Centralization? Of ownership and returns, in that case.

Centralization is antithetical to the original, somewhat punk Bitcoin ethos. Web3 advocates, as far as I can tell it, are perfectly content with using external funds to power their new token-based projects as a way to accelerate the future they see coming. Fiat as crutch, I suppose.

But Bitcoin didn’t need to raise three venture rounds in a year to grow. It just nailed an idea that still resonates. Something to think about.

Now we get to a very large yeah, but.

Bitcoin is religion; web3 is greed

While it’s nice to agree with someone on a crypto viewpoint, I don’t agree with Jack on everything.

For example, I don’t agree that Bitcoin is not centralized. It is to a degree that I don’t think that many people really grok. A new study found this week that “approximately 0.01% of Bitcoin holders control 27% of the 19 million Bitcoin that are now in circulation,” per Baystreet.

This is why, when I consider the two warring religious camps in the crypto world — the Bitcoin maximalists who think that the original crypto project is a decentralized Jesus and the web3 “gm” crew — it’s clear that they are rather different.

Bitcoin maxis are religious in their belief that the OG crypto nailed it, and successive projects are bunk. And web3 is greed, a way to financialize everything online in a manner that allows traditional investors to own toll booths and tax collectors throughout the decentralized landscape.

So while I am more than content to nod along to Jack stirring the web3 pot, I don’t agree with his general philosophy. Still, Jack managed to point out that a bunch of naked wannabe emperors are, in fact, au naturel. And that’s a good way to kick off the day.

Merry Christmas.