A new report has peeled back the curtain on big tech’s frenzied lobbying of European Union lawmakers as they finalize a major series of updates to the bloc’s digital rulebook.

It reveals some of the arguments used by tech giants including Apple, Amazon, Google, Meta (Facebook) and Spotify to press their interests behind the scenes in a bid to reshape key components of the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act (DSA) — targeting areas such as surveillance advertising and access to platform data for researchers — with the clear intent of shielding their processes and business models from measures that could weaken their market power.

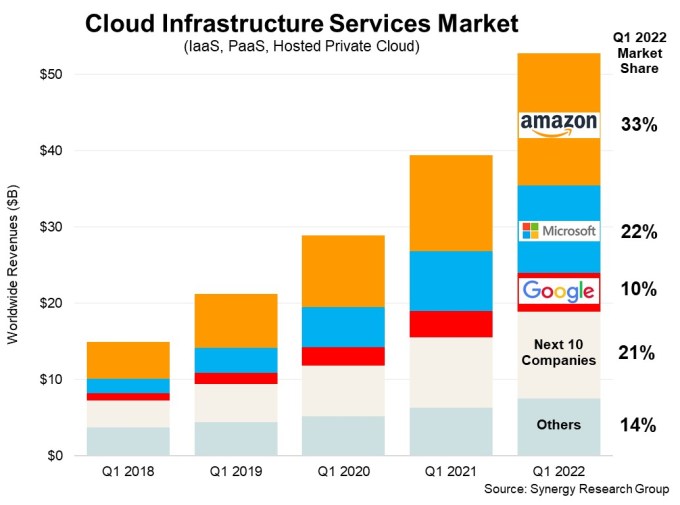

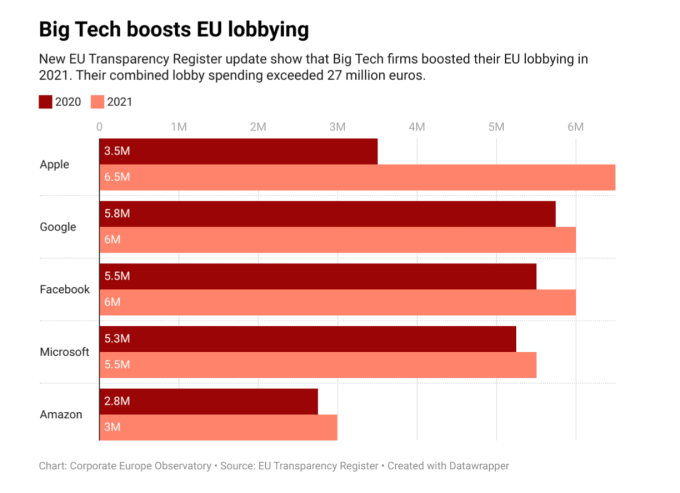

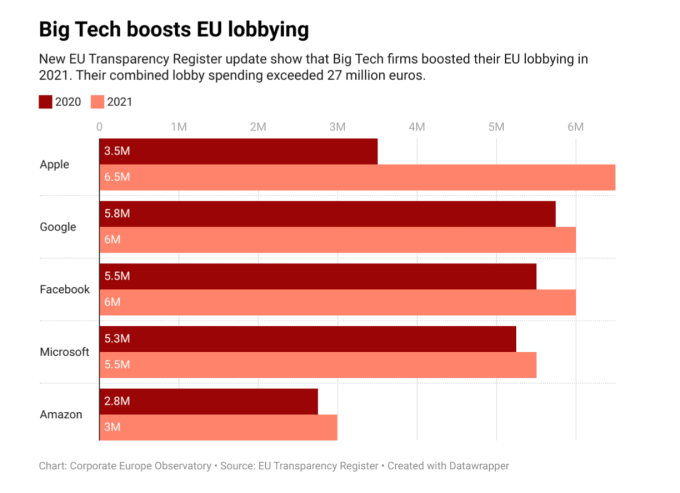

The report, which is based on lobbying documents obtained by civil society groups Corporate Europe Observatory and Global Witness via freedom of information requests, also highlights how tech giants have ramped up their spending on regional lobbying since the DMA and DSA were proposed back in December 2020 — with the big five collectively spending over €27M (close to $30M) last year alone.

It concludes with a series of recommendations for how policymakers can better protect the democratic process from undue influence by the best resourced corporate giants.

Spend, spend, spend!

Citing publicly disclosed data, the report shows that Apple has increased its spending on EU lobbying the most — almost doubling how much it’s shelling out from €3.5M in 2020 to €6.5M in 2021, meaning it also pulled into the lead among platform peers for total regional lobbying spend last year.

Facebook (Meta) had the next biggest increase, growing the size of its EU lobbying budget from €5.5M in 2020 to €6M in 2021. Google also topped up its outlay from €5.8M in 2020 to €6M. While Amazon and Microsoft both made similar increases in regional spending over this period.

Image credit: Corporate Europe Observatory

The DMA, which gained political agreement last month, will apply only to the largest and most powerful intermediary platforms — so called “gatekeepers”; a designation that’s likely to apply to the five ‘big spenders’ in the above chart — introducing a set of operational obligations these giants must abide by up-front.

The pan-EU regulation, which is expected to come into force in October, aims to reboot competition in digital markets dominated by gatekeepers and ensure they remain open and fair.

Its sister regulation — the DSA — applies more broadly, setting rules for all sorts of digital services which are intended to harmonize online approaches to tackling illegal content and products. This means it touches on areas like content moderation, consumer protection and transparency. And while it applies across digital services a subset of so-called “very large online platforms” (aka VLOPs) will be subject to additional oversight under the regulation — meaning that tech giants will face additional DSA compliance hurdles vs smaller players.

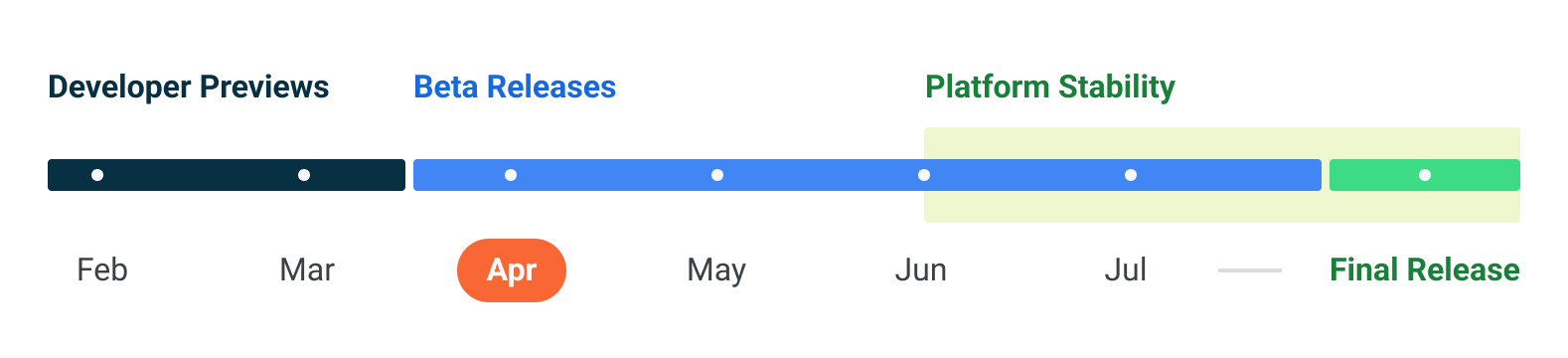

At the time of writing the DSA is still pending political agreement — although a deal is expected after Friday’s (April 22) trilogue meeting — so the impact of big tech’s lobbying on EU policymaking should become clearer in the coming days.

So what have tech giants been spending their millions on lobbying for as EU lawmakers finalize the DSA and DMA?

Read on for a breakdown of their focus areas from the report…

Surveillance advertising

One major target for Big Tech lobbyists, per the report, has been around surveillance advertising as tech giants marshalled their millions to block off an attempt to get an outright ban on tracking-based advertising into EU legislation.

They succeeded in that goal as an earlier push by some MEPs for an outright ban did not gain full backing of the parliament so did not make it into the trilogue discussions. But the European Parliament did vote to incorporate limits on tracking ads into both the DSA and the DMA — with MEPs backing a ban on processing of minors’ data for targeting ads and a ban on use of sensitive categories of personal data.

However the Council position diverged from parliament, toeing closer to the Commission’s original proposal — which had merely suggested ads transparency requirements — so tech giants sought to exploit this to try to water down restrictions on tracking ads, per the report.

Documents obtained for the report show that Google directly lobbied the Commission in a series of high level meetings with top commissioners between November and early January in which the adtech giant raised concerns about the European Parliament’s proposals on advertising — suggesting limits on trackings would be detrimental to SMEs and harm news publishers.

“This marked a continuation of Google and Facebook’s strategy throughout the whole discussion on new digital regulations — trying to reframe it away from Big Tech’s immense profits and business model and to instead hype up potential negative impacts for smaller businesses and consumers,” the report notes. “As Google’s leaked lobbying strategy showed, one of its priorities was to focus the discussion on the costs to the economy and consumers.”

Between January to the end of March, lobby documents show that Google remained in frequent contact with the Swedish government — arguing on four different occasions against Parliament’s proposal to ban advertising targeted at minors and other limits, per the report. “Their recommendation to national governments was to ‘support the Council / Commission position (i.e. no restraints on targeted ads’). Google argued ‘that the DSA is not the right forum to deal with these issues’,” it adds.

There’s a special irony here given Google also led big tech lobbying efforts to delay an update to the bloc’s ePrivacy rules — which explicitly cover tracking technologies like cookies. That update remains stalled even now (the Commission proposal was presented all the way back in January 2017!). So if the tech giant were to have its way there would, it seems, be no ‘appropriate’ legal forum to rein in its surveillance ads empire. Funny that!

But as it turns out, EU lawmakers in the Council and Parliament were able to agree — through the trilogue process — on including limits to tracking ads.

At least that was the position announced last month, at the moment of political agreement on the DMA.

At the time of writing the Commission is signalling that limits on targeting advertising will be included in the DSA, with internal market commissioner, Thierry Breton, including a ban on targeted advertising to children or based on sensitive data in a tweet storm highlighting “10 things you need to know” about the regulation, for example…

Under the political deal reached between EU co-legislators last month, the DMA requires gatekeepers to gain explicit consent from users to combine their personal data for advertising.

But the French presidency of the Council also said then that they had agreed complementary provisions to limit tracking ads would also be included in the text of the DSA (still to be agreed via trilogue) — signalling that the parliament’s goal of limits on processing children’s data for ads or using sensitive data for ads would make it into EU law.

So what did Google’s lobbyists do next? According to the report, the tech giant continued pushing against any/all limits on surveillance ads — but also evolved the lobbying tactic, by suggesting to Member States governments ways in which restrictions could be watered down in the final text to limit their impact on its ability to track and target web users.

“On 22 March 2022, the day of the final DMA trilogue, Google sent the Swedish government its thoughts for future trilogue meetings,” notes the report. “Google’s positions reflected the up to date state of the ongoing discussions. Google continued to oppose concrete new proposals regarding user consent to tracking and banning the use of sensitive data for advertising. Perhaps more interesting though, Google now seemed to understand that likely there would be some new limits to targeted advertising. So Google offered suggestions about how these should be drafted: the ban on targeting minors should be limited to ‘known minors’ and behaviour advertising should be defined as the use of individual profiling.”

As the report points out, Google’s fall back positions here are no accident — given that the tech giant has been working for several years to retool its tracking apparatus — under its so-called Privacy Sandbox plan — which proposes to switch from individual-level tracking and targeting to cohort or (now) topic-based targeting which will continue to subject web users to behavioral targeting just now putting them into buckets of eyeballs, not solo pairs.

So — to spell it out — if EU lawmakers were to limit the definition of behavioral advertising as Google suggests it could simply circumvent any limits on its flavor of behavioral advertising by saying it does not target individuals ergo the legal restriction simply doesn’t apply.

Similarly, a final text that would ban advertising to “known minors” would allow Google to claim it does not know the age of users who are not logged into its services (and potentially even users who are logged in as it does not explicitly age verify users) — again avoiding the need to restrict its behavioral targeting by default across most services (barring any it directly targets at children, such as YouTube kids).

Per the report, Google’s lobbyists didn’t stop there. They also sought to water down ad transparency requirements — pushing back against proposals that would allow users to know the criteria used to target them specifically, including when ads were targeted at kids and — in “detailed suggestions” to national governments — proposed that they should “seek to delete the obligation to disclose the criteria used for targeting, even when ads target vulnerable people like children”.

“The documents show Google taking a central position lobbying against limits to surveillance ads,” the report adds. “But they weren’t alone. Facebook, and other European companies [including Spotify] and publishers also resorted to trying to persuade national governments to oppose the Parliament’s position.”

Another big target for Big Tech tech lobbying was around data access for NGOs and public scrutiny…

Public scrutiny

On this issue, which is core to the DSA’s ability to deliver on the goal of ramping up accountability around major platforms, the report details particular moves by Spotify and Google to limit how much access external researchers can gain to platform data — such as to carry out research into the societal impact of recommender algorithms.

Civil society groups have been pushing to strengthen the Commission proposal in this area — to increase external scrutiny of VLOPs by forcing them to give access to data on algorithmic content ranking systems to vetted external researchers so they can study their function.

But Spotify and Google have been busy pushing back against closer scrutiny of how their AIs rank and recommend content to users, per the report.

“The world’s biggest music streaming service didn’t want the transparency requirements to include detailed lists of parameters, as was introduced by the Parliament. On the other hand, it welcome the Parliament’s last-minute introduction of exceptions to recommender transparency, including the protection of intellectual property and trade secrets,” runs one section on Spotify’s lobbying.

“In March this year, Spotify followed up to add its comments ‘regarding the latest compromise proposals on Recommender Systems’. The company supported the ‘evolution of the text’ regarding recommender transparency and welcomed ‘a clarification in a Recital that these rules do not prejudice IP [intellectual property] rights and trade secrets’,” it adds.

Google, meanwhile, was lobbying Member State governments to limit data access for public authorities and vetted researchers to urgent health threats. So in this scenario Europeans might have to wait for the next pandemic to get external scrutiny of YouTube’s recommender engine!

Where the DSA will actually end up on this issue isn’t clear at the time of writing.

Google also questioned whether non-profits organizations should get data — seeking to spread fear that this could put “user data and privacy and confidentiality of information at risk”, according to lobbying documents obtained for the report.

“The company asked national governments to oppose the Parliament’s position and instead support the Council’s mandate. Taken all together, Google’s suggestions would make external scrutiny of the ways in which services like Youtube amplify or de-prioritise content nearly impossible,” it adds.

The report also reveals Google opposed proposals that would require platforms to “make the information on the main parameters for recommender systems and the functionality to opt-out from personalised recommendations directly accessible from the content itself” — presumably because that would make it too easy for users to figure out how to turn off unwanted content recommendations.

‘DMA? Er, just give us a chance to explain first…’

On the DMA, Google, Amazon, Apple and Facebook were all spotted in documents obtained for the report trying to soften the proposal during its last stage.

Apple, for example, brought its (now) familiar argument against moves to force it to open up its App Store and mobile OS, such as by allowing sideloading of apps or other types of interoperability, to discussion tables in the region.

“The company’s main argument was that increasing data access, sideloading and interoperability would reduce user privacy and security,” the report notes, going on to conclude: “While Apple could not successfully stop interoperability and sideloading entirely, the final text does introduce a security safeguard, which will enable the company to try to justify not complying with these obligations.”

It also highlights one particular strand of collective lobbying by Big Tech targeting the DMA that looks intended to enable a repeat show of an oft used tactic against enforcement of existing EU laws which threaten how they like to operate — such as the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). This tactic boils down to one word: Delay.

Per the report:

“[T]he top level message from the Big Tech companies to policy-makers regarding the DMA was the same across the board: Big Tech wanted to build a dialogue between the DMA’s regulator — the European Commission — and the companies covered by it — the gatekeepers, into the text and the regulatory approach.

“They brought this wish up consistently at the high level meetings, such as the December meeting between Google and [Margrethe] Vestager’s cabinet. There Google said that regarding the DMA their ‘core argument towards the Parliament was the need for regulatory dialogue and the opportunity to individually justify certain practices’. Google repeated the same message to Breton’s cabinet in January — ‘Proper regulatory dialogue is important to ensure the enforcement of the DMA’.

“On the very same day, Nick Clegg, Facebook’s head lobbyist, told Commissioner [Didier] Reynders, that for Facebook ‘it would be helpful to have the possibility of having a dialogue with regulators on questions concerning compliance’.

“Amazon, in turn, told the Swedish government that it was ‘more comfortable with content of the Council compromise proposal than with the European Parliament’s amendments.’ The company also raised concerns that specific measures had been moved from Article 6 to Article 5, which would mean they would be automatically applicable and not dependent on a regulatory dialogue.”

Thing is, the whole point of the DMA is to bring in an ex ante competition regime for the bloc — via a set of ‘dos and don’ts’ that are supposed to apply up front for companies designated as gatekeepers, i.e. rather than antitrust authorities having to do the slow and painstaking work of building a case against a particular abusive behavior while the market suffers.

But there is — potentially — a sliver of wiggle room, at least for obligations set out in Article 6 of the DMA. For those requirements, the regulation allows for a dialogue between the Commission and relevant companies over how best to comply.

Which, well, sounds like it could be spun into delay heaven.

The report summarizes the main aim of Big Tech’s lobby campaign against the DMA as being to “expand this dialogue as much as possible”, with Corporate Europe Observatory noting it fingered this as a key priority for Facebook, Google and Apple since last summer. It also quotes another lobby transparency group, Lobbycontrol, which has argued that Big Tech’s aim here is to “gain time — and first of all an entrance point for challenging the DMA’s obligations.”

The painstakingly slow ‘regulatory dialogue‘ which Facebook and other tech giants have managed to establish with their lead EU privacy regulator — Ireland’s Data Protection Commission — since (and, indeed, even before) the GDPR came into force in 2018, enabling them to successful delay enforcement despite multiple open investigations into a variety of aspects of their businesses, is likely providing Clegg & co with plentiful inspiration for the sort of friction-filled conversation they want signed off and baked into the DMA to create a legally viable ‘back and forth’ that lets them delay actually changing abusive practices for as long as humanly possible.

It’s not yet clear how successful the tech giants have been in this regard.

However the Commission has, in recent weeks, been spotted making some concerning noises on the topic of DMA enforcement to anyone who actually wants to see regulators crack down on Big Tech, as consumer protection experts have observed…

“Ultimately the scope of regulatory dialogue in the DMA has been changed to allow the gatekeepers to initiate it. However, it will still be up to the Commission to decide whether or not to engage. We will have to wait and see how this plays out in practice,” is the report’s cautious conclusion on this.

In recent days, others have raised concerns about another potential loophole in the DMA — which, if they’re right, could see a history of failed GDPR enforcement against Big Tech tech being leveraged by the self-same giants to avoid freshly inked obligations in the DMA. Earlier this month, the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL) drew together signatures from a long list of competition and privacy experts to a letter that warns of “a severe flaw in Article 5(1)a of the latest DMA text” which they suggest will “help Big Tech firms undermine data protection and competition”.

The concern is that gatekeepers will continue to evade the GDPR’s purpose limitation principle by bundling consent for combining user data across multiple services into a single opt-in — thereby making it harder for users to deny — which is essentially how adtech giants like Facebook have evaded existing EU regulations, continuing to track and target web users in the region despite the GDPR’s requirement for unbundled consent (Facebook does not offer an opt out of behavioral advertising; to use its service you have to ‘agree’ to being profiled for ads).

The parliament’s rapporteur on the DMA file, MEP Andreas Schwab, has rejected the concern in recent days — suggesting that the DMA does not change the GDPR. And indeed, in a letter responding to the ICCL which we’ve reviewed, that “the consent requirement under the DMA builds on the GDPR consent”. He has also claimed there’s “no need to fear circumvention” because the Commission will be in charge of enforcement. Aka, no more forum shopping.

However signatories to the letter continue to warn that gaps in GDPR enforcement create a problem for effectively enforcing the DMA — unless the Commission acts quickly to provide guidance and bring cases.

“Gatekeepers will try to use the ambiguity to their advantage,” warns the ICCL’s Johnny Ryan. “It is essential that the Commission issues quick and clear guidance and enforcement decisions to stop that.”

Structural weakness?

How EU lawmaking is structured means the Commission’s legislative proposals are typically modified, via a co-legislative process, which loops in the (directly elected) European Parliament and Member States’ national government representatives, via the European Council — which together amend, vote and negotiate to try to reach a compromise on the final details of the law.

This means that there are, at least from one perspective, multiple point at which lobbyists can seek to influence — or indeed block — EU policymaking.

This starts with the Commission itself, as the EU’s executive body drafts and thus frames legislative proposals; moving on to MEPs who play a key role by voting for amendments and to set the parliament’s negotiating position (typically prefigured via committee vote/s); and extending to Member States’ governments which are represented on the Council and lead the so-called trilogue negotiations with the Parliament and Commission to seek a compromise via a rotating presidency structure that sees one Member State (currently France) responsible for producing compromise texts on behalf of the Council.

So, in short, it’s a lobbyists’ picnic!

The latter stage trilogue negotiations are especially problematic, being conducted entirely behind closed doors — thereby reducing transparency on how exactly policy is being reshaped, as the report underlines:

“This process is one of the most secretive stages of EU policy-making, held entirely behind closed doors and with nearly no public access to the discussions. The EU Institutions have argued that this secrecy is needed in part to prevent lobbying pressure on the policy-makers.

“New lobby documents obtained from the European Commission and the Swedish government via freedom of information requests show that intense corporate lobbying is happening regardless of the lack of transparency.”

The details that the civil society groups were able to glean on big tech’s lobbying around the DMA and DSA are only partial, as the report notes that responses to freedom of information requests varied.

However they say the documents they did obtain showed that tech giants like Google continued to target the trilogue process even after the Council had agreed its negotiating positions — meaning they are shown trying to grasp a very last minute, non-transparent opportunity to favorably water down measures that could shrink their market power.

“We can now confirm that corporate lobbying of EU capitals continues even after the Council agrees its positions and starts trilogue negotiations with the Parliament and Commission,” the report authors write. “While only Sweden gave us extensive access to these documents, we can expect that all EU governments must be on the receiving end of similar lobby efforts.”

“The lobby documents also reveal that Google remained in frequent contact with the Swedish government from January to the end of March (the time when we placed our freedom of information request). During this period, the tech giant would send in analysis of the difference positions, adding the company’s own analysis, and all the while replicating the EU Institutional format of documents with four columns,” they go on. “As the discussions went on behind closed doors, Google pitched in with ‘specific language on articles currently discussed’ and suggested ‘concrete amendments’, showing a strikingly live knowledge of what was happening in the negotiation process.”

According to the report, Google, Apple, Amazon and Facebook — alongside European firms such as Spotify and the copyright industry — actively sought to influence the trilogues themselves, meaning they were trying to exert influence during the least transparent point of the co-legislative process.

The lobbying tactics they are reported to have used included:

- pitting the EU Institutions against one another;

- becoming more technical and offering amendments to the text;

- using meetings to gain access to information that was not available to the public;

- going high level: bringing in the CEOs to meet Commissioners, inviting them to off the record dinners.

Corporate Europe Observatory and Global Witness argue that this evidence of lobbying taking place during trilogues “shows how the lack of transparency benefits big corporate lobbies and adds weight to the urgency of finally opening the trilogues process up to the public” — further suggesting: “This secrecy means that only the well-resourced and well-connected lobbying actors can follow and intervene in trilogues, and excludes citizens from crucial discussions that will have an impact on their lives.”

“National governments have a say in EU policy-making via the Council. This is often referred to as the EU’s ‘black box’, as it is difficult for citizens to know who is lobbying their national government on EU policies, or even what position their national government takes in the Council. This approach, combined with the fact that lobbying at member state level requires massive resources and good connections, creates the conditions for undue corporate influence,” they add.

The report makes a series of recommendations to protect EU policymaking against undue influence by the most well-resourced lobbyists, based on the NGOs’ tracking and analysis of the DSA and DMA process since the drafting stages.

Its suggestions include shedding light into the trilogues by publishing an up-to-date calendar of meetings, including summary agendas, and proactively publishing the four-column document (which details co-legislator positions and amendments) on a rolling basis; boosting transparency and democratic accountability at the Member State and Council level including by requiring disclosure of each country’s position; putting limits on one-to-one lobby meetings and replacing them with public hearings as much as possible; and requiring EU institutions to proactively seek out those who have less resources, such as SMEs, independent academics, civil society and community groups.

Other recommendations include beefing up the existing EU Transparency Register to improve transparency on lobbying; putting in place proper funding transparency requirements that mandate think tanks and other organisations to reveal their funding sources; strengthening ethics rules to block the revolving door between EU institutions and Big Tech firms and establishing an independent ethics committee which can launch investigations and implement sanctions.

The report authors also urge EU officials and policymakers to be sceptical of those lobbying them — writing that they “should question their funding sources, check their information and data sources and denounce any type of wrongdoing or non-transparent/unethical lobbying they encounter”.

They also recommend they should not attend or participate in events or debates that are closed to the public, held under Chatham House rules, or that do not disclose their sponsorship.