Is our age of ubiquitous smartphones and social media turning into an era of mass civil unrest? Two years after holding an independence referendum and unilaterally declaring independence in defiance of the Spanish state — then failing to gain recognition for la república and being forced to watch political leaders jailed or exiled — Catalonia’s secessionist movement has resurfaced with a major splash.

One of the first protest actions programmed by a new online activist group, calling itself Tsunami Democràtic, saw thousands of protestors coalescing on Barcelona airport Monday, in an attempt to shut it down. The protest didn’t quite do that but it did lead to major disruption, with roads blocked by human traffic as protestors walked down the highway and the cancelation of more than 100 flights, plus hours of delays for travellers arriving into El Prat.

For months leading up to a major Supreme Court verdict on the fate of imprisoned Catalan political leaders a ‘technical elite‘ — as one local political science academic described them this week — has been preparing to reboot Catalonia’s independence movement by developing bespoke, decentralized high-tech protest tools.

A source with knowledge of Tsunami Democràtic, speaking to TechCrunch on condition of anonymity, told us that “high level developers” located all around the world are involved in the effort, divvying up coding tasks as per any large scale IT project and leveraging open source resources (such as the RetroShare node-based networking platform) to channel grassroots support for independence into a resilient campaign network that can’t be stopped by the arrest of a few leaders.

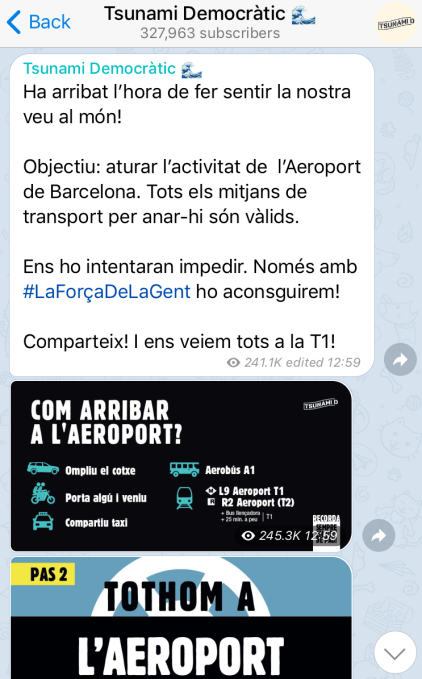

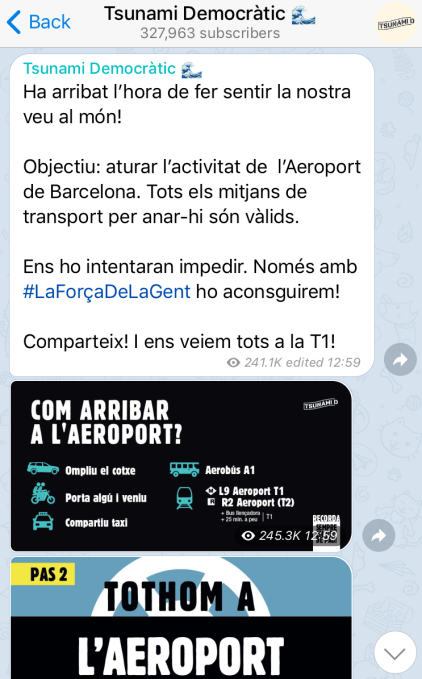

Demonstrators at the airport on Monday were responding directly to a call to blockade the main terminal posted to the group’s Telegram channel.

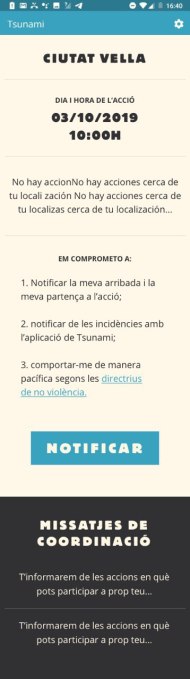

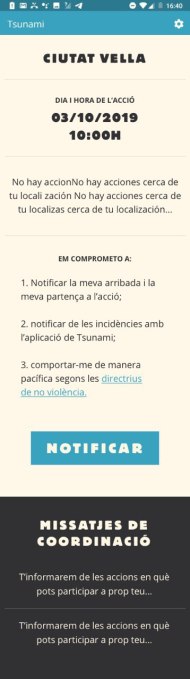

Additional waves of protest are being planned and programmed via a bespoke Tsunami Democràtic app that was also released this week for Android smartphones — as a sideload, not yet a Google Play download.

The app is intended to supplement mainstream social network platform broadcasts by mobilizing smaller, localized groups of supporters to carry out peaceful acts of civil disobedience all over Catalonia.

Our source walked us through the app, which requires location permission to function in order that administrators can map available human resources to co-ordinate protests. We’re told a user’s precise location is not shared but rather that an obfuscated, more fuzzy location marker gets sent. However the app’s source code has not yet been open sourced so users have to take such claims on trust (open sourcing is said to be the plan — but only once the app has been scrubbed of any identifying traces, per the source).

The app requires a QR code to be activated. This is a security measure intended to manage activation in stages, via trusted circles of acquaintances, to limit the risk of infiltration by state authorities. Though it feels a bit like a viral gamification tactic to encourage people to spread the word and generate publicity organically by asking their friends if they have a code or not.

Whatever it’s really for the chatter seems to be working. During our meeting over coffee we overheard a group of people sitting at another table talking about the app. And at the time of writing Tsunami Democràtic has announced 15,000 successful QR code activations so far. Though it’s not clear how successful the intended flashmob civil disobedience game-plan will be at this nascent stage.

Once activated, app users are asked to specify their availability (i.e. days and times of day) for carrying out civil disobedience actions. And to specify if they own certain mobility resources which could be utilized as part of a protest (e.g. car, scooter, bike, tractor).

Examples of potential actions described to us by our source were go-slows to bring traffic grinding to a halt and faux shopping sprees targeting supermarkets where activists could spend a few hours piling carts high with goods before leaving them abandoned in the store for someone else to clean up.

One actual early action carried out by activists from the group last month targeted a branch of the local CaixaBank with a masked protestor sit-in.

Our source said the intention is to include a pop-up in the app as a sort of contract of conscience which asks users to confirm participation in the organized chaos will be entirely peaceful. Here’s an example of what the comprometo looks like:

Users are also asked to confirm both their intention to participate in a forthcoming action (meaning the app will capture attendance numbers for protests ahead of time) and to check in when they get there so its administrators can track actual participation in real-time.

The app doesn’t ask for any personal data during onboarding — there’s no account creation etc — although users are agreeing to their location being pervasively tracked.

And it’s at least possible that other personal data could be passed via, for example, a comment submission field that lets people send feedback on actions. Or if the app ends up recording other data via access to smartphone sensors.

The other key point is that users only see actions related to their stated availability and tracked location. So, from a protestor’s point of view, they see only a tiny piece of the Tsunami Democràtic protest program. The user view is decentralized and information is distributed strictly piecemeal, on a need to know basis.

Behind the scenes — where unknown administrators are accessing its data and devising and managing protest actions to distribute via the app — there may be an entirely centralized view of available human protest resources. But it’s not clear what the other side of the platform looks like. Our source was unable to show it to us or articulate what it looks like.

Certainly, administrators are in a position to cancel planned actions if, for example, there’s not enough participation — meaning they can invisibly manage external optics around engagement with the cause. Not enough foot soldiers for a planned protest? Just call it off quietly via the app.

Also not at all clear: Who the driving forces are behind the Tsunami Democràtic protest mask?

“There is no thinking brain, there are many brains,” a spokesman for the movement told the El Diario newspaper this week. But that does raise pretty major questions about democratic legitimacy. Because, well, if you’re claiming to be fighting for democracy by mobilizing popular support, and you’re doing it from inside a Western democracy, can you really claim that while your organization remains in the shadows?

Even if your aim is non-violent political protest, and your hierarchy is genuinely decentralized, which is the suggestive claim here, unless you’re offering transparency of structure so as to make your movement’s composition and administration visible to outside scrutiny (so that your claims of democratic legitimacy can be independently verified) then individual protestors (the app’s end users) just have to take your word for it.

End users who are being crowdsourced and coopted to act out via app instruction as if they’re pawns on a high tech chess board. They are also being asked (implicitly) to shoulder direct personal risk in order that a faceless movement generates bottom up political pressure.

So there’s a troubling contradiction here for a movement that has chosen to include the word ‘democractic’ in its name. (The brand is a reference to a phase used by jailed Catalan cultural leader, Jordi Cuixart.) Who or what is powering this wave?

We also now know all too well how the double-sided nature of platforms means these fast-flowing technosocial channels can easily be misappropriated by motivated interest groups to gamify and manipulate opinion (and even action) en masse. This has been made amply clear in recent years with political disinformation campaigns mushrooming into view all over the online place.

So while emoji-strewn political protest messages calling for people to mobilize at a particular street corner might seem a bit of harmless ‘Pokemon Go’-style urban fun, the upshot can — and this week has — been far less predictable and riskier than its gamified packaging might suggest.

Plenty of protests have gone off peacefully, certainly. Others — often those going on after dusk and late into the night — have devolved into ugly scenes and destructive clashes.

There is clearly a huge challenge for decentralized movements (and indeed technologies) when it comes to creating legitimate governance structures that don’t simply repeat the hierarchies of the existing (centralized) authorities and systems they’re seeking to challenge.

The anarchy-loving crypto community’s inability to coalesce around a way to progress with blockchain technology looks like its own self-defeating irony. A faceless movement fighting for ‘democracy’ from behind an app mask that allows its elite string-pullers and data crunchers to remain out of sight risks looking like another.

None of the protestors we’ve spoken to could say for sure who’s behind Tsunami Democràtic. One suggested it’s just “citizens” or else the same people who helped organize the 2017 Catalan independence referendum — managing the movement of ballot papers into and out of an unofficial network of polling stations so that votes could be collected and counted despite Spanish authorities’ best efforts to seize and destroy them.

There was also a sophisticated technology support effort at the time to support the vote and ensure information about polling stations remained available in the face of website takedowns by the Spanish state.

Our source was equally vague when asked who is behind the Tsunami Democràtic app. Which, if the decentralizing philosophy does indeed run right through the network — as a resilience strategy to protect its members from being ratted out to the police — is what you’d expected.

Any single node wouldn’t know or want to know much of other nodes. But that just leaves a vacuum at the core of the thing which looks alien to democratic enquiry.

One thing Tsunami Democràtic has been at pains to make plain in all (visible) communications to its supporters is that protests must be peaceful. But, again, while technology tools are great enablers it’s not always clear exactly what fire you’re lighting once momentum is pooled and channeled. And protests which started peacefully this week have devolved into running battles with police with missiles being thrown, fires lit and rubber bullets fired.

Some reports have suggested overly aggressive police response to crowds gathering has triggered and flipped otherwise calm protestors. What’s certain is there are injuries on both sides. Today almost 100 people were reported to have been hurt across three nights of protest action. A general strike and the biggest manifestation yet is planned for Friday in Barcelona. So the city is braced for more trouble as smartphone screens blink with fresh protest instructions.

Social media is of course a conduit for very many things. At its most corporate and anodyne its stated mission can be expressed flavorlessly — as with Facebook’s claimed purpose of ‘connecting people’. (Though distracting and/or outraging is often closer to the mark.)

In practice, thanks to human nature — so that means political agendas, financial interests and all the rest of our various and frequently conflicting desires — all sorts of sparks can fly. None more visibly than during mass mobilizations where groups with a shared agenda rapidly come together to amplify a cause and agitate for change.

Even movements that start with the best intentions — and put their organizers and administration right out in the open for all to see and query — can lose control of outcomes.

Not least because malicious outsiders often seize the opportunity to blend in and act out, using the cover of an organized protest to create a violent disturbance. (And there have been some reports filtering across Catalan social media claiming right wing thugs have been causing trouble and that secret police are intentionally stirring things up to smear the movement.)

BARCELONA, SPAIN – OCTOBER 17: Protesters take to the streets to demonstrate after the Spanish Supreme Court sentenced nine Catalan separatist leaders to between 9 and 13 years in prison for their role of the 2017 failed Catalan referendum on October 17, 2019 in Barcelona, Spain. (Photo by Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images)

So if a highly charged political campaign is being masterminded and micromanaged remotely, by unknown entities shielded behind screens, there are many more questions we need to be asking about where the balance of risk and power lies, as well as whether a badge of ‘pro-democracy’ can really be justified.

For Tsunami Democràtic and Catalonia’s independence movement generally this week’s protests look to be just the start of a dug-in, tech-fuelled guerrilla campaign of civil disobedience — to try to force a change of political weather. Spain also has yet another general election looming so the timing offers the whiff of opportunity.

The El Prat blockade that kicked off the latest round of Catalan unrest seemed intended to be a flashy opening drama. To mirror and reference the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong — which made the international airport there a focal point for its own protests, occupying the terminal building and disrupting flights in an attempt to draw the world’s attention to their plight.

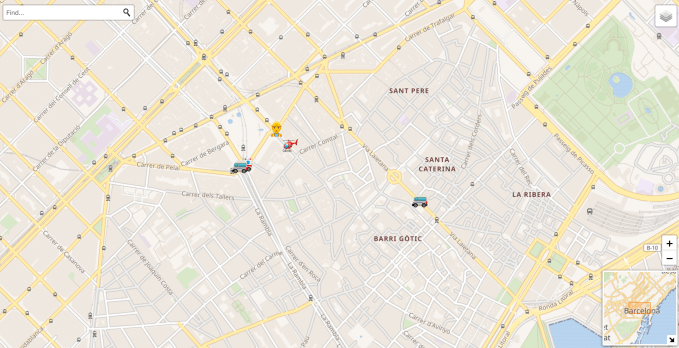

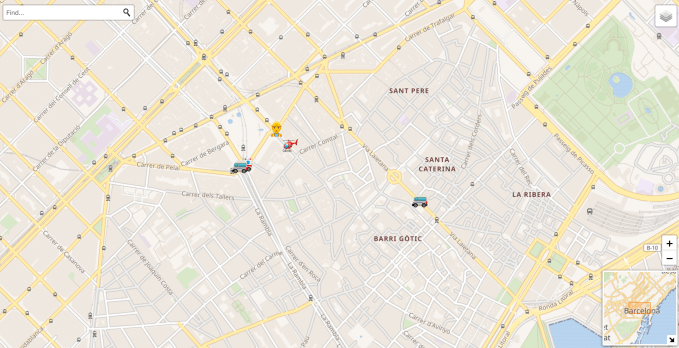

In a further parallel with protests in Hong Kong a crowdsourced map similar to HKmaps.live — the app that dynamically maps street closures and police presence by overlaying emoji onto a city view — is also being prepared for Catalonia by those involved in the pro-independence movement.

At the time of writing a handful of emoji helicopters, road blocks and vans are visible on a map of Barcelona. Tapping on an emoji brings up dated details such as what a police van was doing and whether it had a camera. A verified status suggests multiple reports will be required before an icon is displayed. We understand people will be able to report street activity for live-mapping via a Telegram bot.

Screenshot of Catalan live map for crowdsourcing street intel

Our source suggested police presence on the map might be depicted by chick emojis. Aka Piolín: The Spanish name for the Loony Tunes cartoon character Tweety Pie — a reference to a colorfully decorated cruise ship used to house scores of Spanish national police in Barcelona harbor during the 2017 referendum, providing instant meme material. Though the test version we’ve seen seems to be using a mixture of dogs and chicks.

Along with the Tsunami Democràtic app the live map means there will soon be two bespoke tools supporting a campaign of civil disobedience whose unknown organizers clearly hope will go the distance.

As we’ve said, the identities of the people coordinating the rebooted movement remain unclear. It’s also unclear who if anyone is financing it.

Our source suggested technical resources to run and maintain the apps are being crowdsourced by volunteers. But some commentators argue that a source of funding would be needed to support everything that’s being delivered, technically and logistically. The app certainly seems far more sophisticated than a weekend project job.

There has been some high level public expressions of support for Tsunami Democràtic — such as from former Barcelona football club trainer, Pep Guardiola, who this week put out a video badged with the Tsunami D logo in which he defends the democratic right to assembly and protest, warning that free speech is being threatened and claiming “Spain is experiencing a drift towards authoritarianism”. So wealthy backers of Catalan independence aren’t exactly hard to find.

Whoever is involved behind the scenes — whether with financing or just technical and organization support — it’s clear that ‘free’ protest energy is being liberally donated to the cause by a highly engaged population of pro-independence supporters.

Grassroots support for Catalan independence is both plentiful, highly engaged, geographically dispersed and cuts across generations — sometimes in surprising ways. One mother we spoke to who said she was too ill to go to Monday’s airport protest recounted her disappointment when her teenage kids told her they weren’t going because they wanted to finish their homework.

Very many protestors did go though, answering calls to action in their messaging apps or via the printable posters made available online by Tsunami Democràtic which some street protestors have been pictured holding.

Thousands of demonstrators occupied the main Barcelona airport terminal building, sat and sang protest songs, daubed quasi apologetic messages on the windows in English (saying a lack of democracy is worse than missing a flight), and faced off to lines of police in riot gear — including units of Spanish national police discharging rubber bullets. One protestor was later reported by local press to have lost an eye.

‘It’s time to make our voice heard in the world,’ runs Tsunami Democràtic’s message on Telegram calling for a blockade of the airport. It then sets out the objective (an airport shut down) and instructs supporters that all forms of transport are “valid” to further the mission of disrupting business as usual. ‘Share and see you all at T1!’ it ends. Around 240,000 people saw the instruction, per Telegram’s ephemeral view counts.

Demonstrators during a protest against the jailing of Catalan separatists at El Prat airport in Barcelona, Spain, on Monday, Oct. 14, 2019. (Photo by Iranzu Larrasoana Oneca/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Later the same evening the channel sent another message instructing protestors to call it a night. ‘Today we have been a tsunami,’ it reads in Catalan. ‘We will make every victory a mobilization. We have started a cycle of non-violent, civil disobedience.’ At the time of writing that follow-on missive has registered 300k+ views.

While Tsunami Democràtic is just one of multiple pro-independence groups arranging and mobilizing regional protests — such as the CDRs, aka Comites de Defensa de la Republica, which have been blocking highways in Catalonia for the past two years — it’s quickly garnered majority momentum since quietly uncloaking this summer.

Its Telegram channel — which was only created in August — has piled on followers in recent weeks. Other pro-independence groups are also sharing news and distributing plans over Telegram’s platform and, more widely, on social media outlets such as twitter. Though none has amassed such a big following, nor indeed with such viral speed.

Even Anonymous Catalonia’s Telegram channel, which has been putting out a steady stream of unfiltered crowdsourced protest content this week — replete with videos of burning bins, siren blaring police vans and scattering crowds, interspersed with photos of empty roads (successful blockades) and the odd rubber bullet wound — only has a ‘mere’ 100k+ subscribers.

And while Facebook-owned WhatsApp was a major first source of protest messaging around the 2017 Catalan referendum, with Telegram just coming on stream as an alternative for trying to communicate out of sight of the Spanish state, the protest mobilization baton appears to have been passed more fully to Telegram now.

Perhaps that’s partly due to an element of mistrust around mainstream platforms controlled by tech giants who might be leant on by states to block content (Tsunami Democràtic has said it doesn’t yet have an iOS version of its app, despite many requests for one, because the ‘politics of the App Store is very restrictive’ — making a direct reference to Apple pulling the HKmaps app from its store). Whereas Telegram’s founder, Pavel Durov, is famously resistant to authoritarian state power.

Though, most likely, it’s a result of some powerful tools Telegram provides for managing and moderating channels.

The upshot is Telegram’s messaging platform has enjoyed a surge in downloads in Spain during this month’s regional unrest — as WhatsApp-loving locals flirt with a rival platform also in response to calls from their political channels to get on Telegram for detailed instructions of the next demo.

Per App Annie, Telegram has leapt up the top free downloads charts for Google Play in Spain — rising from eleventh place into the third spot this month. While, for iOS, it’s holding steady in the top free downloads slot.

Also growing in parallel: Unrest on Catalonia’s streets.

Since Monday’s airport protest tensions have certainly escalated. Roads across the region have been blockaded. Street furniture and vehicles torched. DIY missiles thrown at charging police.

By Thursday morning there were reports of police firing teargas and police vehicles being driven at high speed around protesting crowds of youths. Two people were reported run over.

Anti-riot police officers shoot against protesters after a demonstration called by the local Republic Defence Committees (CDR) in Barcelona on October 17, 2019. – After years of peaceful separatist demonstrations, violence finally exploded on the Catalan streets this week, led by activists frustrated by the political paralysis and infuriated by the Supreme Court’s conviction of nine of its leaders over a failed independence bid. (Photo by LLUIS GENE / AFP) (Photo by LLUIS GENE/AFP via Getty Images)

Helicopters have become a routine sound ripping up the urban night sky. While the tally of injury counts continues rising on both sides. And all the while there are countless videos circulating on social media to be sifted through to reinforce your own point of view — screening looping clashes between protestors and baton wielding police. One video doing the rounds last night appeared to show protestors targeting a police helicopter with fireworks. Russian propaganda outlets have of course been quick to seize on and amplify divisive visuals.

The trigger for a return to waves of technology-fuelled civil disobedience — as were also seen across Catalonia around the time of the 2017 referendum — are lengthy prison terms handed down by Spain’s Supreme Court on Monday. Twelve political and civic society leaders involved in the referendum were convicted, nine on charges of sedition and misuse of public funds. None were found guilty of the more serious charge of rebellion — but the sentences were still harsh, ranging from 13 years to nine.

The jailed leaders — dubbed presos polítics (aka political prisoners) by Catalan society, which liberally deploys yellow looped-ribbons as a solidarity symbol in support of the presos — had already spent almost two years in prison without bail.

A report this week in El Diario, citing a source in Tsunami Democràtic, suggests the activist movement was established in response to a growing feeling across the region’s independence movement that a new way of mobilizing and carrying out protests was needed in the wake of the failed 2017 independence bid.

The expected draconian Supreme Court verdict marked a natural start-date for the reboot.

A reboot has been necessary because, with so many of its figureheads in prison — and former Catalan president Carles Puigdemont in exile in Brussels — there has been something of a leadership vacuum for the secessionist cause.

That coupled with a sense of persecution at the hands of a centralized state which suspended Catalonia’s regional autonomy in the wake of the illegal referendum, invoking a ‘nuclear option’ constitutional provision to dismiss the government and call fresh elections, likely explains why the revived independence movement has been taking inspiration from blockchain-style decentralization.

Our source also told us blockchain thinking has informed the design and structure of the app.

Discussing the developers who have pulled the app together they said it’s not only a passionately engaged Catalan techie diaspora, donating their time and expertise to help civic society respond to what’s seen as long-standing political persecution, but — more generally — coders and technologists with an interest in participating in what they hope will be the largest experiment in participatory democracy and peaceful civil disobedience.

The source pointed to research conducted by Erica Chenoweth, a political scientist at Harvard University, who found non-violent, civil disobedience campaigns to be a far more powerful way of shaping world politics than violence. She also found such campaigns need engage only 3.5% of the population to succeed. And at 300k+ subscribers Tsunami Democràtic’s Telegram channel may have already passed that threshold, given the population of Catalonia is only around 7.6M.

It sounds like some of the developers helping the movement are being enticed by the prospect of applying powerful mobile platform technologies to a strong political cause as a way to stress testing democratic structures — and perhaps play at reconfiguring them. If the tools are successful at capturing intention and sustaining action and so engaging and activating citizens in a long term political campaign.

We’re told the stated intention to open source the app is also a goal in order to make it available for other causes to pick up and use to press for change. Which does start to sound a little bit like regime change as a service…

Stepping back, there is also a question of whether micromanaged civic disobedience is philosophically different to more organic expressions of discontent.

There is an element of non-violent protest being weaponized against an opponent when you’re running it via an app. Because the participants are being remotely controlled and coordinated at a distance, at the same time as ubiquitous location-sensitive mobile technologies mean the way in which the controlling entity speaks to them can be precisely targeted to push their buttons and nudge action.

Yes, it’s true that the right to peaceful assembly and protest is a cornerstone of democracy. Nor is it exactly a new phenomenon that mobile technology has facilitated this democratic expression. In journalist Giles Tremlett’s travelogue book about his adopted country, Ghosts of Spain, he recounts how in the days following the 2004 Madrid train bombings anonymous text messages started to spread via mobile phone — leading to mass, spontaneous street demonstrations.

At the time there were conflicting reports of who was responsible for the bombings, as the government sought to blame the Basque terrorist group ETA for what would turn out to be the work of Islamic terrorists. Right on the eve of an election voters in Spain were faced with a crucial political decision — having just learnt that the police had in fact arrested three Moroccans for the bomb attacks, suggesting the government had been lying.

“A new political phenomenon was born that day — the instant text message demonstration,” Tremlett writes. “Anonymous text messages began to fly from mobile phone to mobile phone. They became known as the pásalo messages, because each ended with an exhortation to ‘Pass it on’. It was like chain mail, but instant.”

More than fifteen years on from those early days of consumer mobile technology and SMS text messaging, instant now means so much more than it did — with almost everyone in a wealthy Western region like Catalonia carrying a powerful, Internet-connected computer and streaming videocamera in their pocket.

Modern mobile technology turns humans into high tech data nodes, capable of receiving and transmitting information. So a protestor now can not only opt in to instructions for a targeted action but respond and receive feedback in a way that makes them feel personally empowered.

From one perspective, what’s emerging from high tech ‘push button’ smartphone-enabled protest movements, like we’re now seeing in Catalonia and Hong Kong, might seem to represent the start of a new model for democratic participation — as the old order of representative democracy fails to keep pace with changing political tastes and desires, just as governments can’t keep up technologically.

But the risk is it’s just a technological elite in the regime-change driving seat. Which sums to governance not by established democratic processes but via the interests of a privileged elite with the wealth and expertise to hack the system and create new ones that can mobilize citizens to act like pawns.

Established democratic processes may indeed be flawed and in need of a degree of reform but they have also been developed and stress-tested over generations. Which means they have layers of accountability checks and balances baked in to try to balance out competing interests.

Throwing all that out in favor of a ‘democracy app’ sounds like the sort of disruption Facebook has turned into an infamous dark art.

For individual protestors, then, who are participating as willing pawns in this platform-enabled protest, you might call it selfie-style self-determination; they get to feel active and present; they experience the spectacle of political action which can be instantly and conveniently snapped for channel sharing with other mobilized friends who then reflect social validation back. But by doing all that they’re also giving up their agency.

Because all this ‘protest’ action is flowing across the surface of an asymmetric platform. The infrastructure natively cloaks any centralized interests and at very least allows opaque forces to push a cause at cheap scale.

“I felt so small,” one young female protestor told us, recounting via WhatsApp audio message, what had gone down during a protest action in Barcelona yesterday evening. Things started out fun and peaceful, with participants encouraged to toss toilet rolls up in the air — because, per the organizer’s messaging, ‘there’s a lot of shit to clean up’ — but events took a different turn later, as protestors moved to another location and some began trying to break into a police building.

A truck arrived from a side street being driven by protestors who used it to blockade the entrance to the building to try to stop police getting out. Police warning shots were fired into the air. Then the Spanish national police turned up, driving towards the crowd at high speed and coming armed with rubber not foam bullets.

Faced with a more aggressive police presence the crowd tried to disperse — creating a frightening crush in which she was caught up. “I was getting crushed all the time. It wasn’t fun,” she told us. “We moved away but there was a huge mass of people being crushed the whole time.”

“What was truly scary weren’t the crowds or the bullets, it was not knowing what was going on,” she added.

Yet, despite the fear and uncertainty, she was back out on the streets to protest again the next night — armed with a smartphone.

Enric Luján, a PhD student and adjunct professor in political science at the University of Barcelona — and also the guy whose incisive Twitter thread fingers the forces behind the Tsunami Democràtic app as a “technological elite” — argues that the movement has essentially created a “human botnet”. This feels like a questionable capability for a pro-democracy movement when combined with its own paradoxically closed structure.

“The intention appears to be to group a mass movement under a label which, paradoxically, is opaque, which carries the real risk of a lack of internal democracy,” Luján tells TechCrunch. “There is a basic paradox in Tsunami Democràtic. That it’s a pro-democracy movement where: 1) the ‘core’ that decides actions is not accessible to other supporters; 2) it has the word ‘Democràtic’ in its name but its protocols as an organization are extremely vertical and are in the hands of an elite that decides the objectives and defines the timing of mobilization; 3) it’s ‘deterritorialized’ with respect to the local reality (unlike the CDRs): opacity and verticality would allow them to lead the entire effort from outside the country.”

Luján believes the movement is essentially a continuation of the same organizing forces which drove support for pro-independence political parties around the 2017 referendum — such as the Catalan cultural organization Òmnium — now coming back together after a period of “strategic readjustment”.

“Shortly after the conclusion of the referendum, through the arrest of its political leaders, the independence movement was ‘decapitated’ and there were months of political paralysis,” he says, arguing that this explains the focus on applying mobile technology in a way that allows for completely anonymous orchestration of protests, as a strategy to protect itself from further arrests.

“This strategic option, of course, entails lack of public scrutiny of the debates and decisions, which is a problem and involves treating people as ‘pawns’ or ‘human botnets’ acting under your direction,” he adds.

He is also critical of the group not having opened the app’s code which has made it difficult to understand exactly how user data is being handled by the app and whether or not there are any security flaws. Essentially, there is no simple way for outsiders to validate trustworthiness.

His analysis of the app’s APK raises further questions. Luján says he believes it also requests microphone permissions in addition to location and camera access (the latter for reading the QR code).

Our source told us that as far as they are aware the app does not access the microphone by default. Though screenshots of requested permissions which have circulated on social media show a toggle where microphone access seems as if it can be enabled.

And, as Luján points out, the prospect of a powerful and opaque entity with access to the real-time location of thousands of people plus the ability to remotely activate smartphone cameras and microphones to surveil people’s surroundings does sound pretty close to the plot of a Black Mirror episode…

Asked whether he believes we’re seeing an emergent model for a more participatory, grassroots form of democracy enabled by modern mobile technologies or a powerful techie elite playing at reconfiguring existing power structures by building and distributing systems that keep them shielded from democratic view where they can nudge others to spread their message, he says he leans towards the latter.

“It’s a movement with an elite leadership that seems to have had a clear timetable for months. It remains to be seen what they’ll be able to do. But it is clearly not spontaneous (the domain of the website was registered in July) and the application needed months to develop,” he notes. “I am not clear that it can be or was ‘crowdsourced’ — as far as I know, there was no campaign to finance Tsunami or their technological solutions.”

“Release the code,” he adds. “I don’t understand why they haven’t released it. Promising it is easy and is what you expect if you want to present yourself with a minimum of transparency, but there is no defined deadline to do so. For now we have to work with the APK, which is more cumbersome to understand how the app works and how it uses and moves user data.”

“I imagine it is so the police cannot investigate thoroughly, but it also means others lose the possibility of better understanding how a product that’s been designed by people who rely on anonymity works, and have to rely that the elite technologists in charge of developing the app have not committed any security breach.”

So, here too, more questions and more uncertainty.