One big theme in tech right now is the rise of services to help us keep working through lockdowns, office closures, and other Covid-19 restrictions. The “future of work” — cloud services, communications, productivity apps — has become “the way we work now.” And companies that have identified ways to help with this are seeing a boom.

Today comes news from a startup that has been a part of that trend: Calendly, a popular cloud-based service that people use to set up and confirm meeting times with others, has closed an investment of $350 million from OpenView Venture Partners and Iconiq.

The funding round includes both primary and secondary money (slightly more of the latter than the former, from what I understand) and values the Atlanta-based startup at over $3 billion.

Not bad for a company that before now had raised just $550,000, including the life savings of the founder and CEO, Tope Awotona, to initially get off the ground.

Calendly is a freemium software-as-a-service, built around what is essentially a very simple piece of functionality.

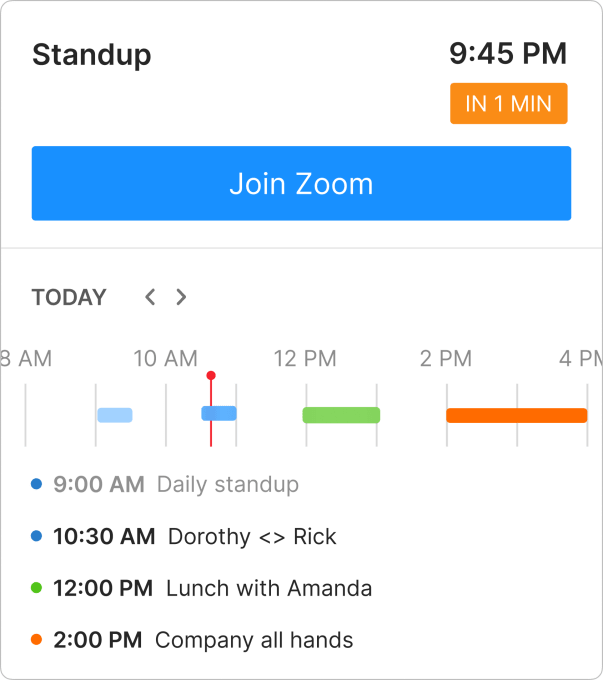

It’s a platform that provides a quick way to manage open spaces in your calendar for people to book appointments with you in those spaces, which then also books out the time in calendars like Google’s or Microsoft Outlook — with a growing number of tools to enhance that experience, including the ability to pay for a service in the event that your appointment is not a business meeting but, say, a yoga class. Pricing ranges from free (one calendar/one user/one event) to premium ($8/month) and pro ($12/month) for more calendars, events, integrations and features, with bigger packages for enterprises also available.

Its growth, meanwhile, has to date been based mostly around a very organic strategy: Calendly invites become links to Calendly itself, so people who use it and like it can (and do) start to use it, too.

The wide range of its use cases, and the virality of that growth strategy, have been winners. Calendly is already profitable, and it has been for years. And more recently, it has seen a boost, specifically in the last twelve months, as new Calendly users have emerged, as a result of how we are living.

We may not be doing more traditional “business meetings” per week, but the number of meetings we now need to set up, has gone up.

All of the serendipitous and impromptu encounters we used to have around an office, or a neighborhood coffee shop, or the park? Those are now scheduled. Teachers and students meeting for a remote lesson? Those also need invitations for online meetings.

And so do sessions with therapists, virtual dinner parties, and even (where they can still happen) in-person meetings, which are often now happening with more timed precision and more record-keeping, to keep social distancing and potential contact tracing in better order.

Currently, some 10 million of us are using Calendly for all of this on a monthly basis, with that number growing 1,180% last year. The army of business users from companies like Twilio, Zoom, and UCSF has been joined by teachers, contractors, entrepreneurs, and freelancers, the company says.

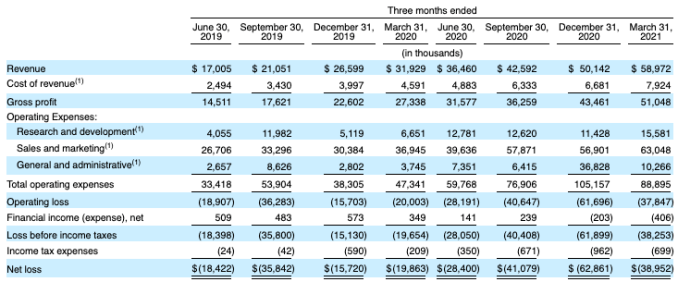

The company last year made about $70 million annually in subscription revenues from its SaaS-based business model and seems confident that its aggregated revenues will not long from now get to $1 billion.

So while the secondary funding is going towards giving liquidity to existing investors and early employees, Awotona said the plan will be to use the primary capital to invest in the company’s business.

That will include building out its platform with more tools and integrations — it started with and still has a substantial R&D operation in Kiev, Ukraine — expanding its operations with more talent (it currently has around 200 employees and plans to double headcount), further business development and more.

Two notable moves on that front are also being announced with the funding: Jeff Diana is coming on as chief people officer with a mission to double the company’s employee base. And Patrick Moran — formerly of Quip and New Relic — is joing as Calendly’s first chief revenue officer. Notably, both are based in San Francisco — not Atlanta.

That focus for building in San Francisco is already a big change for Calendly. The startup, which is going on eight years old, has been somewhat off the radar for years.

That is in part due to the fact that it raised very little money up to now (just $550,000 from a handful of investors that include OpenView, Atlanta Ventures, IncWell and Greenspring Associates).

It’s also based in Atlanta, an increasingly notable city for technology startups and other companies but more often than not short on being credited for its heft in that department (SalesLoft, Amex-acquired Kabbage, OneTrust, Bakkt, and many others are based there, with others like Mailchimp also not too far away).

And perhaps most of all, proactively courting publicity did not appear to be part of Calendly’s growth playbook.

In fact, Calendly might have closed this big round quietly and continued to get on with business, were it not for a short Tweet last autumn that signaled the company raising money and shaping up to be a quiet giant.

“The company’s capital efficiency and what @TopeAwotona has built deserve way more credit than they get,” it read. “Perhaps this will start to change that recognition.”

After that short note on Twitter — flagged on TechCrunch’s internal message board — I made a guess at Awotona’s email, sent a note introducing myself, and waited to see if I would get a reply.

I eventually did get a response, in the form of a short note agreeing to chat, with a Calendly link (naturally) to choose a time.

(Thanks, unnamed TC writer, for never writing about Calendly when Tope originally pitched you years ago: you may have whet his appetite to respond to me.)

In that first chat over Zoom, Awotona was nothing short of wary.

In that first chat over Zoom, Awotona was nothing short of wary.

After years of little or no attention, he was getting cold-contacted by me and it seems others, all of us suddenly interested in him and his company.

“It’s been the bane of my life,” he said to me with a laugh about the calls he’s been getting.

Part of me thinks it’s because it can be hard and distracting to balance responding to people, but it’s also because he works hard, and has always worked hard, so doesn’t understand what the new fuss is about.

A lot of those calls have been from would-be investors.

“It’s been exorbitant, the amount of interest Calendly has been getting, from backers of all shapes and sizes,” Blake Bartlett, a partner at OpenView, said to me in an interview.

From what I understand, it’s had inbound interest from a number of strategic tech companies, as well as a long list of financial investors. That process eventually whittled down to just two backers, OpenView and Iconiq.

From Lagos to fixing cash registers

Yet even putting the rumors of the funding to one side, Calendly and Awotona himself have been a remarkable story up to now, one that champions immigrants as well as startup grit.

Tope comes from Lagos, Nigeria, part of a large, middle class household. His mother had been the chief pharmacist for the Nigerian Central Bank, his father worked for Unilever.

The family may have been comfortable, but growing up in Lagos, a city riven by economic disparity and crime, brought its share of tragedies. When he was 12, Awotona’s father was murdered in front of him during a carjacking. The family moved to the U.S. some time after that, and since then his mother has also passed away.

A bright student who actually finished high school at 15, Awotona cut his teeth in the world of business first by studying it — his major at the University of Georgia was management information systems — and then working in it, with jobs after college including periods at IBM and EMC.

But it seems Awotona was also an entrepreneur at heart — if one that initially was not prepared for the steps he needed to take to get something off the ground.

He told me a story about what he describes as his “first foray into business” at age 18, which involved devising and patenting a new feature for cash registers, so that they could use optical character recognition recognize which bills and change were being used for, and dispense the right amount a customer might need in return after paying.

At the time, he was working at a pharmacy while studying and saw how often the change in the cash registers didn’t add up correctly, and his was his idea for how to fix it.

He cold-contacted the leading cash register company at the time, NCR, with his idea. NCR was interested, offering to send him up to Ohio, where it was headquartered then, to pitch the idea to the company directly, and maybe sell the patent in the process. Awotona, however, froze.

“I was blown away,” he said, but also too surprised at how quickly things escalated. He turned down the offer, and ultimately let his patent application lapse. (Computer-vision-based scanning systems and automatic dispensers are, of course, a basic part nowadays of self-checkout systems, for those times when people pay in cash.)

There were several other entrepreneurial attempts, none particularly successful and at times quite frustrating because of the grunt work involved just to speak to people, before his businesses themselves could even be considered.

Eventually, it was the grunt work that then started to catch Awotona’s attention.

“What led me to create a scheduling product” — Awotona said, clear not to describe it as a calendaring service — “was my personal need. At the time wasn’t looking to start a business. I just was trying to schedule a meeting, but it took way too many emails to get it done, and I became frustrated.

“I decided that I was going to look for scheduling products that existed on the market that I could sign up for,” he continued, “but the problem I was facing at the time was I was trying to arrange a meeting with, you know, 10 or 20 people. I was just looking for an easy way for us to easily share our availability and, you know, easily find a time that works for everybody.”

He said he couldn’t really see anything that worked the way he wanted — the products either needed you to commit to a subscription right away (Calendly is freemium) or were geared at specific verticals such as beauty salons. All that eventually led to a recognition, he said, “that there was a big opportunity to solve that problem.”

The building of the startup was partly done with engineers in Kiev — a drama in itself that pivoted at times on the political situation at times in Ukraine (you can read a great unfolding of that story here).

Awotona says that he admired the new guard of cloud-based services like Dropbox and decided that he wanted Calendly to be built using “the Dropbox approach” — something that could be adopted and adapted by different kinds of users and usages.

Simplicity in the frontend, strategy at the backend

On the surface, there is a simplicity to the company’s product: it’s basically about finding a time for two parties to meet. Awotona notes that behind the scenes the scheduling help Calendly provides is the key to what it might develop next.

For example, there are now tools to help people prepare for meetings — specifically features like being able to, say, pay for something that’s been scheduled on Calendly in order to register. A future focus could well be more tools for following up on those meetings, and more ways to help people plan recurring individual or group events.

One area where it seems Calendly does not want to dabble are those meetings themselves — that is, hosting meetings and videoconferencing itself.

“What you don’t want is to start a world war three with Zoom,” Awotona joked. (In addition to becoming the very verb-ified definition of video conferencing, Zoom is also a customer of Calendly’s.)

“We really see ourselves as a leading orchestration platform. What that means is that we really want to remain extensible and flexible. We want our users to bring their own best in class products,” he said. “We think about this in an agnostic way.”

But in a technology world that usually defaults back to the power of platforms, that position is not without its challenges.

“Calendly has a vision increasingly to be a central part of the meeting life cycle. What happens before, during and after the meeting. Historically, the obvious was before the meeting, but now it’s looking at integrations, automations and other things, so that it all magically happens. But moving into the rest of the lifecycle is a lot of opportunity but also many players,” admitted Bartlett, with others including older startups like X.ai and Doodle (owned by Swiss-based Tamedia) or newer entrants like Undock but also biggies like Google and Microsoft.

“It will be an interesting task to see where there are opportunities to partner or build or buy to build out its competitive position.”

You’ll notice that throughout this story I didn’t refer to Awotona’s position as a black founder — still very much a rarity among startups, and especially those valued at over $1 billion.

That is partly because in my conversations with him, it emerged that he saw it as just another detail. Still, it is one that is brought up a lot, he said, and so he understands it is important for others.

“I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about being black or not black,” he said. “It doesn’t change how I approach or built Calendly. I’m not incredibly conscious of my race or color, except for the last few years through he growth of Calendly. I find that more people approach me as a black tech founder, and that there is young black people who are inspired by the story.”

That is something he hopes to build on in the near future, including in his home country.

Pending pandemic chaos, he has plans to try to visit Nigeria later this year and to get more involved in the ecosystem in that country, I’m guessing as a mentor if not more.

“I just know the country that produced me,” he said. “There are a million Topes in Nigeria. The difference for me was my parents. But I’m not a diamond in the rough, and I want to get involved in some way to help with that full potential.”

We’ll wrap at the end with a summary of what we’ve learned and also make sure to check out the company’s marketing spend, because I’m sure you’ve seen its digital ads.

We’ll wrap at the end with a summary of what we’ve learned and also make sure to check out the company’s marketing spend, because I’m sure you’ve seen its digital ads.

Successful businesses make technology work for them, not the other way round. When used correctly, technology can make every task much easier to accomplish. So if you’re looking to increase staff efficiency, incorporate technology into your daily operations with the following methods.

Successful businesses make technology work for them, not the other way round. When used correctly, technology can make every task much easier to accomplish. So if you’re looking to increase staff efficiency, incorporate technology into your daily operations with the following methods. Technology enables businesses to work remotely, collaborate more efficiently, and manage their time more effectively. But to achieve these benefits, you need to implement technologies that align with your business’s needs. Here are some things to consider.

Technology enables businesses to work remotely, collaborate more efficiently, and manage their time more effectively. But to achieve these benefits, you need to implement technologies that align with your business’s needs. Here are some things to consider. Technology can provide countless opportunities to streamline workflows, eliminate redundant processes, and reduce costs. If you’re looking to stay ahead of the competition, simple technology strategies like the ones below can dramatically enhance your business performance.

Technology can provide countless opportunities to streamline workflows, eliminate redundant processes, and reduce costs. If you’re looking to stay ahead of the competition, simple technology strategies like the ones below can dramatically enhance your business performance.

More and more organizations across the globe are migrating their data and systems to Microsoft 365. If you’re thinking about making the move yourself, take note of the following common mistakes to ensure your migration is successful and hassle-free.

More and more organizations across the globe are migrating their data and systems to Microsoft 365. If you’re thinking about making the move yourself, take note of the following common mistakes to ensure your migration is successful and hassle-free. Migrating to Microsoft 365 is easy and simple, but if you’re not careful, you may find yourself facing problems that can keep you from getting the most out of this comprehensive suite of productivity tools. We’ve listed some of the common issues organizations encounter when migrating to Microsoft 365 and how you can avoid them.

Migrating to Microsoft 365 is easy and simple, but if you’re not careful, you may find yourself facing problems that can keep you from getting the most out of this comprehensive suite of productivity tools. We’ve listed some of the common issues organizations encounter when migrating to Microsoft 365 and how you can avoid them. With over 200 million monthly active users worldwide, Microsoft 365 is a powerhouse in the productivity tools market. It combines all the products and services your team needs to get their jobs done efficiently. But for your organization to truly leverage the benefits of Microsoft 365, you must ensure a smooth migration by avoiding these mistakes.

With over 200 million monthly active users worldwide, Microsoft 365 is a powerhouse in the productivity tools market. It combines all the products and services your team needs to get their jobs done efficiently. But for your organization to truly leverage the benefits of Microsoft 365, you must ensure a smooth migration by avoiding these mistakes.

Windows is the most popular operating system in history, but despite its popularity, many users still do not know about all of its functionalities. Here are some Windows 10 features from the latest update that you might have missed.

Windows is the most popular operating system in history, but despite its popularity, many users still do not know about all of its functionalities. Here are some Windows 10 features from the latest update that you might have missed. Did you know that the latest update of the Windows 10 operating system comes with many improvements to user experience? Try out the following features and change the way you work, play, and everything in between.

Did you know that the latest update of the Windows 10 operating system comes with many improvements to user experience? Try out the following features and change the way you work, play, and everything in between.