For four weeks during 2021, this TechCrunch reporter took the plunge and tested a “metabolic fitness” service from Bangalore-based startup Ultrahuman. The tracker program, branded Cyborg, uses arm-mounted medical grade hardware to get a real-time read-out of your blood glucose — using that dynamic data-point to power a quantified health service that scores what you eat and how you move, nudging you to make healthier lifestyle choices throughout the day.

Research has linked chronic metabolic inflammation, from factors such as poor diet and physical inactivity, to the risk of developing a number of diseases — from diabetes to cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease and even cancer. So the theory behind the product is that lots of incremental lifestyle choices can stack up to a healthier long term outlook — if you’re able to ‘optimize’ these decisions to avoid triggers for inflammation and oxidative stress.

Here follows my long read on the curious experience of living with a skin-perforating wearable and a dynamically updating digital window onto your biological process, as well as wider discussion of the value of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) for a general health/fitness purpose, and — finally — some notes on the competitive landscape springing up around productizing this type of sensing hardware.

As this is loosely a review of Ultrahuman’s (still private beta) product/service, I’ve also included a ‘Verdict & Price’ section too. Skip ahead if you want to dive into the operational details. But first some context…

Preamble & Caveats

Becoming a cyborg is no longer as sci-fi as that sounds. For years the ‘quantified self’ trend has spawned all sorts of sensors and services for measuring bodily activity and nudging you to track and ‘optimize’ your outputs — from step counters and heart rate monitors, to stress and sleep sensors, lung capacity scorers, and, more recently, freakier stuff: Blood glucose monitors and saliva or pee/poop analyzers — the latter for delving into hormonal and/or microbiome/metabolic health if you’re so inclined.

Serving the worried well with wrist-mounted, strapped on or otherwise self-administered sensing technology plus a subscription service to play pocket oracle — via an app-delivered interpretation of what all this personal data means (and ofc how to improve your metrics) — is booming business. Close your (exercise) rings. Breathe more deeply. Try to get to bed earlier, and so on.

Some of this quantified health tech can come across as a bit superficial or frivolous; an attempt to ‘gizmoify’ daily life and push a gadget when you could just go for a walk or get to bed earlier. The more basic products work by selling the motivation-challenged a call to get off the sofa or a replacement for lost childhood structure. Or, well, data-fication as proof of existence.

But it can be horses for courses, too; if you have a sleep disorder or suffer from stress and anxiety then tracking your sleep — and getting little nudges and tips on how get more shut-eye — might be just what you need to lock in quality Zzzs.

Available tech has been getting more sophisticated, too. Although, when commercial trackers put a suggestive focus on organ-function (heart; lung etc), the quantification may sound impressive but can suffer from questionable accuracy — given a lot of this stuff is consumer-grade, rather than (regulated) medical devices.

Even step tracker data can be plenty inexact.

But in a more recent development, a growing number of startups are making use of medical grade sensing hardware to offer self-administered metabolic analysis via tracking (near) real-time changes in blood glucose through the use of a sensor that you ‘wear’ on (and, well, in) the skin.

This is a fascinating and growing but still novel area of focus for quantified health startups. One that looks promising, in terms of being able to serve individually useful health insights and which — given enough data — may be able to scale in utility and help empower many others to make healthier individual lifestyle choices.

But the really big caveat is that scientific understanding of metabolic fitness isn’t yet as complete and holistic as we might hope.

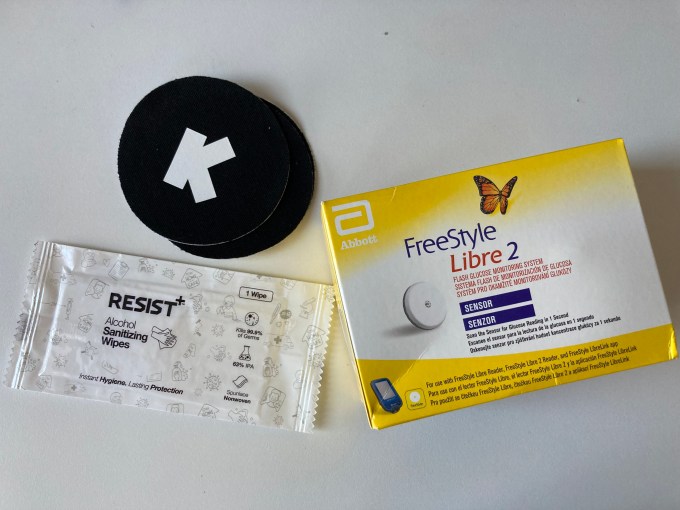

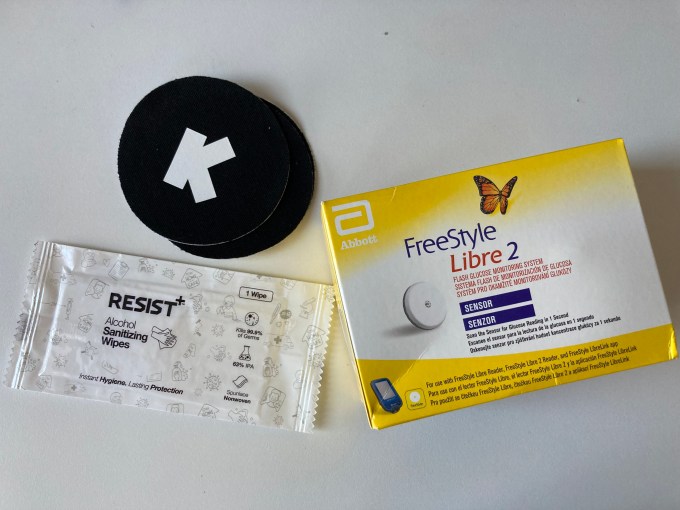

Ultrahuman Cyborg: What’s in the box? Abbott’s CMG sensor, alcohol wipes, tape patches to wear over the sensor (Image credits: Natasha Lomas/TechCrunch)

Much is not understood — such as why there can be so much variation between individuals’ metabolic responses (different people eating the exact same diet can have very different responses, for example); or the exact role of inflammation in the risk of developing diseases like diabetes or cancer.

So the ability of startups to play oracle here is bounded by the need for more research. (Albeit, grabbing data to advance research and understanding is a key part of the opportunity entrepreneurs are spying.)

Nor is the sensing hardware in question regulated for the ‘general wellness’ use-case most of these startups are pursuing.

Which means these services remain novel — aka, experimental — even if the hardware they’re repurposing is legit, in the sense of being manufactured by established medical devices firms, and regulated for narrower use (i.e. diabetes management).

Typically these sensors have regulatory clearance for people with diabetes to track their blood glucose — instead of having to do constant finger prick tests. That may lend credibility to startups hooking into the same device makers’ APIs to grab the same data stream. But the interpretative spin such services put on the data is just that: A spin.

Any wider analysis — including lifestyle recommendations — are definitely not FDA approved.

The debates that have continued to rage back and forth for years around nutrition — all the fad diets, bestselling books and rehashed discussions of what’s good or bad for us to eat, or even what’s effective exercise — is a long-running symptom of a still flawed understanding of the interplay between our biology and what we routinely expose it to.

It’s clear that measuring complex systems without a full understanding of how all the constituent parts can interact and interplay means you’re not going to get the full picture. At best it’s a snapshot — maybe one that supports improved understanding. But it’s never going to have all the answers. So, another word of caution, the risk of misinterpretation is real.

There is also the question of how exactly do you go about measuring ‘metabolic fitness’? As a label it’s a bit of a fuzzy umbrella — arching over complex biological interactions linked to chemical reactions which generate energy in our bodies that may (or may not) mean we’re easily able to maintain a healthy weight; or which can otherwise support or work against us achieving a high level of physical fitness.

What you eat; how; when; and how active and well rested (vs stressed) you were at the time are just a few of the dynamically varying factors that can affect metabolic function. (One illustrative example: What you ate the day before may affect how your body metabolizes a particular foodstuff today.) While the biomarker (or biomarkers) a product chooses to zero in on and track will also, obviously, influence what that “metabolic fitness” service can see — and is able to deduce.

Startups targeting metabolic health are exploring a range of options — from tracking blood glucose, to analyzing the gut microbiome or other bodily excretions (like urine), or looking at a combination of outputs/signals (maybe also factoring in heart rate). Over time more bodily signals are likely to be added to the mix to try to flesh out a fuller understanding — but a lot of the current gen metabolic tracking is best thought of as a piece of the puzzle; a sketch or a rough guess, with more blanks than shading lines.

How to understand — or, well, best interpret — data from a combination of metabolic signals presents no shortage of questions and challenges for those trying to productize the cutting edge of figuring out all this bodily chemistry. As Ultrahuman’s founder acknowledges — telling TechCrunch: “Solving for accuracy of insights that we generate from glucose biomarkers is at the very core of our mission.”

The company’s website also contains a text disclaimer that the Cyborg service provides “general information for athletes to understand their glucose levels and athletic performance”; and does not substitute for a professional medical opinion or consist of healthcare/treatment for specific conditions or medical concerns.

While an entrepreneurial mission to demystify the metabolism — and commercialize the concept of metabolic fitness — remains very much ongoing, a couple of things are clear: 1) Demand to better understand biological function exists (plenty of people, not just elite athletes, are interested in what’s going on with their bodies generally and their metabolism specifically) — and: 2) big but as yet unverifiable claims are being made for what this type of ‘health’ tracking tech could provide an individual user as a long term benefit.

So — another caveat! — anyone keen to get involved with metabolic biohacking needs to be clear about the limitations.

Getting a bit of data is not the same as getting a diagnosis — or even a proper understanding. More data in this context can mean more noise and confusion, not necessarily a clear signal. It may also make you worried about things you shouldn’t.

Another observation: The consumer boom in digital health/wellness tracking over the past decade has been understandably slower on the update when it comes to invasive/semi-invasive wearables. Aka, sensing devices that work by being installed (at least a little bit) inside the body.

Even partially — dipping under the skin so it can stick a sensing filament into the interstitial fluid in the case of Ultrahuman’s Cyborg — the ‘wearable’ metabolic tracking service that’s the main focus of this review. This semi-invasive-sensor-plus-app combo monitors (near) real-time glucose levels as a proxy for understanding and scoring metabolic health — providing the patch-wearer with blood sugar-triggered nudges and alerts to encourage beneficial lifestyle tweaks.

The goal is to support the sensor-wearer to stabilize their glucose levels as they go about their day — avoiding extreme highs or lows — with the overarching mission of reducing inflammation and oxidative stress, which is linked to negative health outcomes.

The suggestion is that, by paying attention to “metabolic fitness” — Ultrahuman’s phrase of choice to describe its mission — and taking little actions related to what you eat and when, and how and when you exercise and sleep — you can avoid or even reverse chronic inflammation that might, over time, lead to developing a metabolic disorder like diabetes, or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or cardiovascular disease.

While the notion of dieting isn’t always overtly promoted by startups productizing CGM technology, blood sugar spikes are also of course associated with the consumption of sugary foods (and with a higher volume of consumption) — both of which can lead to weight gain. So supporting metabolic fitness implies help to obtain and stay a healthy weight too.

With such headline-grabbing potential gains — from reducing the risk of chronic diseases to support for weight management and a smart digital sidekick to boost athletic performance — it’s easy to see why there’s been a major startup scramble to demystify (and monetize) the metabolism.

And when it comes to startup opportunity, a literally ‘wired in’ consumer health tracker is definitely a lot less mainstream than wrist-mounted tracking gear like the Apple Watch — which instantly shrinks competition from consumer tech giants, providing bold entrepreneurs with a chance to shine.

Safe to say, if Apple’s wearable came with a retractable metallic fang embedded in the backplate, the tech giant wouldn’t have shipped anywhere near as many watches, no matter how fancy-looking its glucose-sensing filament. (Apple will surely want to incorporate a needle-free version of glucose monitoring into its Watch, as rumors have suggested, and if the tech works out.)

Piercing the skin just sounds messy (even if it isn’t really). And ofc lots of people hate the idea of needles. That means there is simply more space and opportunity — here at biohacking’s cutting edge (ha!) — for quantified health startups to blaze a trail that seems to go deeper than mainstream consumer tech companies. Quantified self tech that’s not afraid to cross the needle-phobia line certainly feels more serious because it is literally closer to the biological process that’s being tracked.

That said, whether placing a tracker into the skin makes a meaningful difference vs a less intimate sensor placement — in terms of the quality of the data being captured; the analysis of that data; and any resulting recommendations provided to the user — is a tricky-to-answer question. (Indeed, it’s a whole series of questions, depending on context and the execution of the service/s.)

In the case of Ultrahuman’s Cyborg, the startup is careful not to overpromise; its marketing puts the responsibility on users to “work on improving your health with real-time visibility of how food and exercise impact your body, and a score that motivates you to improve every day”, as the minimalist instructions which arrived in the box with the beta product put it.

The metabolic “score” Cyborg gives is personalized, yes, But it’s an abstraction and interpretation of biological processes that still hold plenty of questions for science. So, again, this is really more about being part of a search for answers vs getting a single ‘biological truth’ handed to you on a plate. (In short, there is no plate; there’s just a lot of suggestive data to feast your curiosity on.)

While a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing — maybe even more so when the data in question is attached to your own biology — a glimpse of one’s inner workings is undoubtedly catnip for the curious. And in our digital age, with so much health research information available online at the stroke of a key, who isn’t a little curious on matters of personal biology?

The danger, perhaps, is that a more invasive/intimate sensor placement may lead people to automatically assume this type of tracker is giving higher quality intel (and more personally relevant insights) than the calibre of the data processing — and our wider scientific understanding of metabolic processes — is able to deliver.

Ultrahuman isn’t afraid to push that sci-fi notion as a selling point, though. Hence its overt choice of ‘Cyborg’ branding — which deliberately emphasizes the intradermal sensor placement — the direct interface between the tech and your body — implying that’s the special sauce powering a quantified health service which promises to “nudge you towards better health, one small step at a time”, and without the need for “drastic diet changes” or the tedium/frustration of “generic exercise plans”.

Given how many other startups are also leveraging the same (or similar) CGM hardware, the automagic of obtaining the data is already at risk of being commoditized; it’s how this information gets visualized, analyzed and contextualized for each user that really counts.

Again, though, given all the aforementioned uncertainty around the science, that looks inherently hard to quantify.

Of course cynics might say that makes for a perfect startup opportunity…

Ultrahuman Cyborg: How it works

Tracking dynamic changes in blood glucose is Ultrahuman’s proxy of choice for assessing metabolic health.

Why glucose? Ultrahuman’s CEO and co-founder, Mohit Kumar, says it was the best fit for what they wanted the product to achieve — being “a real-time biomarker that is sensitive to food, stress, sleep and activity”.

“We were looking for biomarkers and methods to personalize the fitness journey for people when we started as well but it took us a year long of experimentation to figure out which biomarker really works for the kind of impact we were looking at. We looked at various biomarkers like HRV [heart rate variability], sleep and respiratory rate but glucose seemed really interesting out of the entire lot because of the feedback it provides on our food aspect of the lifestyle,” he tells TechCrunch.

“This means that we would be able to get instant feedback for these lifestyle factors and what we’ve seen is that instant feedback leads to better actionability. For e.g. a nudge that pushes you to walk after a meal that gives you a spike will lead to better actionability vs a report that gets sent after a day.

“Secondly, there are so many fitness wearables and markers that help you improve your activity performance but there’s nothing that helps you optimize what you eat. Nutrition is generally a blackbox and is way more confusing (given hundreds of diet types and personal preference) but it is probably the most important lifestyle factor given how broken our food ecosystem is.

“This is why we felt going in with glucose makes a ton of sense from a ROI perspective even though it is a semi-invasive biomarker. The private beta is helping us understand what nudges and information helps people make lifestyle changes easily. We’ve seen massive engagement on the platform with app opens / user being around 21 per day and most people seeing real-improvements in their health around the 45th day of usage.”

Tracking blood sugar swings almost as they’re happening — thanks to CGM technology — is immediately a major step up on the patience-challenging business of (traditional) dieting trial and error over a multi-week/month period: Aka, change what you eat/how you exercise and wait and see if it actually moves the scales, weeks or even months later.

Continuous blood glucose tracking (vs repeated finger pricks) has been enabled by the development of CGM hardware in recent years — initially for people with a formal diagnosis of diabetes. But now a growing number of startups are productizing this technology for a more general health-concerned or fitness-focused consumer.

The tech itself has led to some interesting science. See for example this 2018 research paper which showed that glucose dysregulation (i.e. highs or lows outside what’s considered the normal range) were actually pretty common in ‘healthy’ people; i.e. those without a diagnosis of diabetes or pre-diabetes — which wasn’t what the researchers had been expecting to find.

At a basic level, Ultrahuman’s service consists of arm-mounted sensing hardware (a disc-shaped sensor) — which must be replaced every two weeks — plus an app to visualize your blood glucose data and deliver alerts and nudges. You pair each new sensor with the app to continue the tracking.

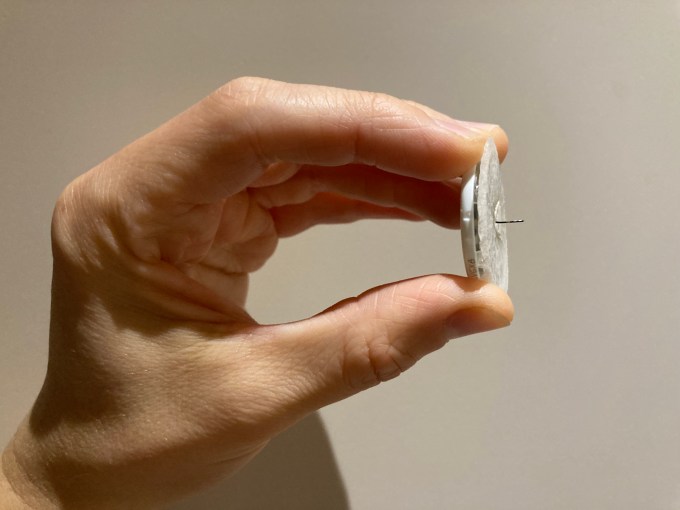

Not your average fitness wearable (Image credits: Natasha Lomas/TechCrunch)

The sensor hardware is made by another company: US medical devices firm, Abbott. The specific sensor that shipped with the Ultrahuman product at the time of writing was Abbott’s FreeStyle Libre 2 flash glucose monitoring system.

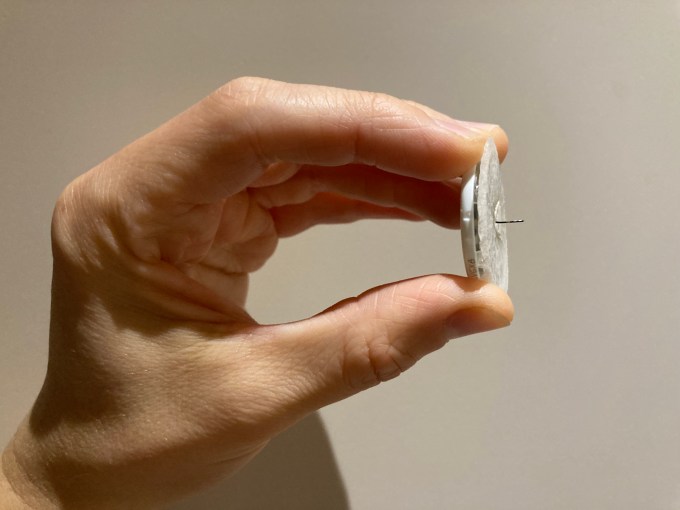

Self administering the CGM sensor is a little nerve wracking but mainly because you only get one shot at (correct) placement. And with only two sensors in the beta box delivered to TechCrunch I didn’t want to waste any hardware.

At the time of application, Ultrahuman had produced a couple of (amusingly robot-voiced) videos to instruct on sensor placement and set up. These were helpful — and only slightly disturbing (owing to the reference not to press too hard to avoid “few drops of blood splatter”).

Abbott’s hardware comes with its own set of instructions and a spring-loaded applicator which you prime manually before positioning the plastic cup on your raised upper arm and, trepidatiously, pressing down to fire the filament into your flesh. The action is rapid enough to make you flinch. It may not help to recall another phrase in Ultrahuman’s instruction video (“hollow needle”). But the needle is just the delivery mechanism for the filament; you’re not going to be left with that bit of visible metal in your arm.

Was there any blood splatter? Not that I noticed. However the second sensor I installed/put on seemed to have fired into a nerve or something as it was pretty painful for several days. After which it sort of settled down/bedded in. Or, well, I got used to it.

The first sensor was not painful, per se, to wear but it definitely takes a bit of getting used to to sleep with a piece of plastic attached to your arm. I found certain yoga poses required extra contortions to avoid uncomfortably pressing down on the sensor, for example. And I swear I could hear a very high pitched whine in my head at night while wearing the CGM — but maybe I was just dreaming of electric sheep.

Yes you can shower/bathe with the sensor in place. Ultrahuman’s box contained a few disc-shaped fabric tape patches to help protect the hardware (and add its branding to your arm). These can start peeling off after a few days depending on your lifestyle but the sensor itself remained firmly lodged for both my two-week stints. (You can remove a dogeared patch and replace it with a fresh one (if you have enough spare). Although that was also nerve wracking as you don’t want early patch removal to prematurely rip out the sensor. So basically it’s about as much fun as applying a whole Macbook decal.)

If you’re curious about the sensing filament itself it feels like a piece of not that fine wire. You get to see it for the first time on extraction from your arm. At which point I saw it looked as if it was coated in some kind of black paint. Which was — I was not too pleased to observe — flaking slightly… But by that time you’ve been living with it in your skin for two weeks so Cyborg acceptance has already taken place. Smart.

The sensor after extraction from my arm (Image credit: Natasha Lomas/TechCrunch)

Was there a mark left? Yeah, a small red bump where the filament had perforated the skin. It faded after a while. The tape itself — including the sensor’s built in fixing (which stayed a lot more firmly attached) — never bothered me.

The sensor pairs with Ultrahuman’s app via Bluetooth. This means it can lose connection if your phone is out of a few meters’ proximity with your arm/person — at which point the data flow (and real-time alerts) will stop. So now you have the perfect excuse for your phone never to leave your side!

If that does happen, the app will notify you and request you to tap the phone back on the sensor when you can to upload any missing readings. (NB: On set up, the sensor also needs a little time to “warm up” — before data starts flowing. So you may find yourself pacing the room as you wait for it to be ready to log your first workout/meal etc.)

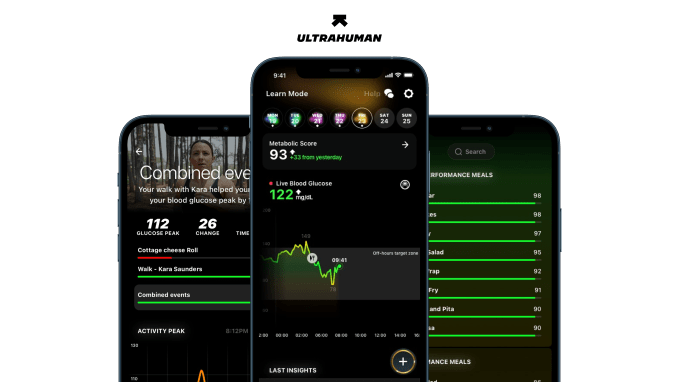

The app itself was a work in progress during TechCrunch’s period of testing which was split over more than a month (as I took a break between applying sensor 1 and sensor 2) — and the software went through a number of changes, including one major visual tweak.

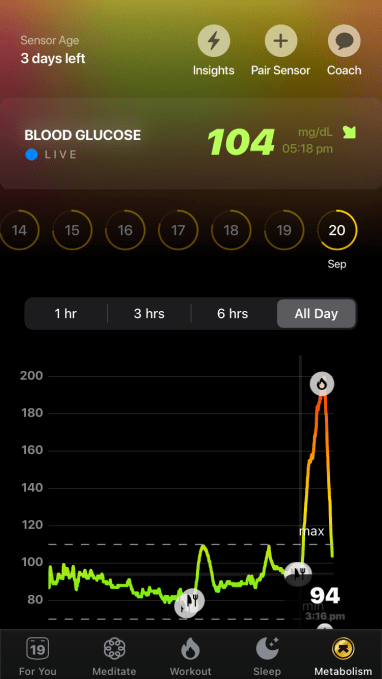

This changed the glucose plot line’s gradient from a too simplistic view (where low-to-high glucose was always displayed as green-to-red) to having a central “target zone” where the plot displays in frosty ‘good to go’ green but as/if rates drop too low or too high they will bleed in a gradient from yellow to orange to red — meaning you can have red highs and lows if you’re out of the optimal glucose range (which is between 70mg/dL and 110mg/dL).

This update was a vast improvement as the earlier version had been visually suggesting that a lower glucose was always better — even if the level was already below target (aka, hypoglycemia) — which it just a small illustration of some of the design/UX pitfalls for this type of quantified health product.

As well as plotting the ups and downs of your blood glucose throughout the day (or at least the approximation which Abbott’s hardware pulls from your interstitial fluid; as any diabetic could tell you, these levels don’t always exactly match blood glucose readings; and if your glucose is rising or falling there can be a short time lag before that shows up in a flash glucose monitor), the app displays what Ultrahuman refers to as a “metabolic score” — which is a number from ‘0’ to ‘100’.

This is the main ‘metric’ mechanic the app uses to try to nudge and gamify healthy lifestyle tweaks.

Ultrahuman describes this score as an indicator of your “overall metabolic health” and says it’s calculated based on glucose variability, average glucose and time in target metrics. The number resets to 100 every day at midnight and decreases or increases “based on your daily lifestyle activities and body’s response”.

The gamification mission sounds very simple: “Your goal is to maximize this score on a daily basis,” as the app puts it.

In practice, getting a ‘good’ (i.e. high) score will depend on your individual biology and lifestyle. And, depressingly, you can wake up with a score that’s already down in the 80s (or, I guess, worse) — depending on what you did/ate earlier.

NB: Stress can also impact blood sugar so events outside your control can impinge on your metrics.

Logging of food — and/or activity or the other types of events which were gradually added to the app during the testing period — is done manually.

Initially this was by custom typing your meal descriptions (or activity). A later update added a food and activity index that lets you search and pick from a structured list and their quantities or times rather than manually typing everything.

In the end, I much preferred custom typing to log food as the list was far too specific and tedious to feel useful. (Type: “Cheese” and it’ll suggest a lot of different types of cheeses — but not necessarily the exact one you’re eating, nor the amount you actually have on your plate, which you may not know in any case; and that’s just one meal ingredient to log; repeating that for a full plate quickly gets old fast… Plus the list also seemed pretty US-centric, which wasn’t very useful for logging a European diet.)

Whereas type in your own favorite cheese — or indeed a custom description of the entire meal — and you can quickly log it next time you eat it as the app will remember your custom label.

Doubtless Ultrahuman is keen to get the best quality structured data that it can — to build the wider utility sought for from predictive AI models. But, if logging feels too much like work, few users will perform the task perfectly for free. So it may have its work cut out to get accurate and structured (vs custom but cryptic) food-to-glucose-response data from its beta user-base.

(Indeed, it may need to rely on asking users to snap an image of their meal and applying computer vision technology to make informed deductions, say, although that may also introduce plenty of errors. Longer term — if the tech goes really mainstream — you could imagine restaurants printing a QR code per meal on their menus which can be scanned so all the correct nutrient data is instantly logged to reduce input friction.)

Activity logging was a lot more straightforward than meals. Not least because, unless you’re an Olympic athlete, you’re going to need to log a lot less of it than food.

After community feedback from beta users, Ultrahuman also added “stress” events as a logging option, as well as fasting — which can of course play havoc with blood glucose but — per some research — may have its own set of health benefits. So giving users more granular options to help better structure the CGM data is sensible.

In the future, automated logging via integration with other types of consumer wearables seems likely. For example, it’s easy to imagine that your fitness band or smart watch detects a specific activity and passes that data to the Ultrahuman app — which could just prompt the user to confirm the details of the detected workout.

For now, though, beta users remain in control of inputting and structuring the data so data quality is likely to be a real smorgasbord.

What I learnt

Ultrahuman’s tips caution that during early use of the product you probably won’t be rewarded with stable, high scores.

This is because learning what you need to do to stabilize your blood glucose typically takes a bit of time — since you have to try different stuff (food pairings, exercise timings etc) to see what works for you. Although this is still a much accelerated process vs the tedious business of old school dieting and fitness regime assessment. (Ofc if you’re blessed with a naturally more stable (i.e. low variation) glucotype you may find you need to do a lot less manual ‘steering’, as it were.)

I will still unprepared for the early horror, though. And spent pretty much the whole first week — jaw on the floor — watching the app lowball score the stuff I usually eat.

Humus salad pita bread sandwich lunch followed by a few walnuts, half an apple and coffee (white, no sugar)? Doesn’t that sound reasonably healthy? Um, apparently not, in my case. It remains one of the all time “bottom zone” lunches during my four weeks as a Cyborg (scoring a big fat ‘0’).

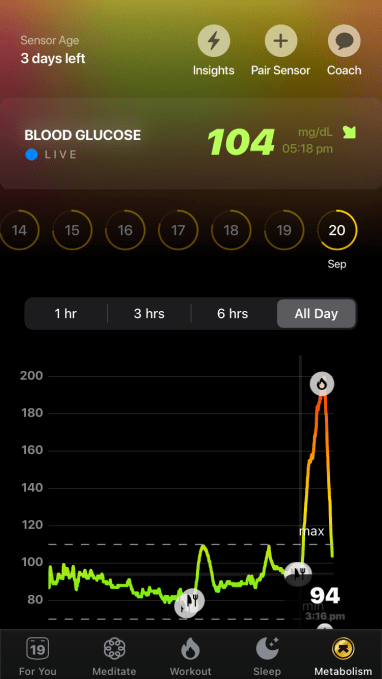

The all time worst lunch food during the test period (purely in terms of how high my glucose peaked after eating) was at least not a dish I had prepared myself but a fast food meal — albeit, from a brand that markets its fare as a “natural” and more healthy choice than traditional McBurgers n chips.

The meal in question — Leon’s lentil masala with brown rice followed by a “regular” coconut milk latte (brand of plant milk: Rude Health); another ‘0’ scorer — produced such an epically large spike that I decided I needed to do an emergency HIIT session just to bring my elevated levels back down again.

The exercise did do the trick. However, if I’d known before lunch that I would need to do do a bunch of burpees and squats right after lunch to metabolise the food spike I might well have revised my food choices.

How continuous glucose monitoring, and mass access to real-time metabolic data, will affect the fast food industry is certainly an interesting question to ponder…

A whopping fast food spike — vanquished by doing some intense exercise (Image credits: Natasha Lomas/TechCrunch)

I hadn’t checked the ingredients small print prior to eating the Leon meal — but eyeing the label suspiciously afterwards, in the red glow of the app’s condemnation, I was unimpressed to find “caster sugar” in a long list of additions.

Although, knowing what I know now, it was probably the coconut milk (an ingredient in both the stew and the coffee) that was especially triggering for me.

Sadly, the post-meal coffee probably didn’t help either.

My least favorite Cyborg learning was that coffee seems to raise my blood sugar. Green tea? Totally fine. Black coffee, decaf, white? All cause me some uplift. And since I like to drink coffee in the afternoon, after eating lunch, that means a raise atop a (food) raise — which might be just enough to tip me into the red.

I still refuse to be a morning coffee person, though.

Rice can also be a spiker for many people — certainly white rice which is more quickly metabolized by the body vs the more fiber-rich wholegrain. Although I’m now more wary of the crash that can come after eating a mainly white rice-based evening meal as it seems to work against keeping blood sugar stable and sustained in the target zone overnight.

Blood sugar lows are just as important to avoid as highs, as it turns out. At least, that’s my sense after four weeks hooked to a CGM. Although my early usage of the app was entirely preoccupied with trying to avoid the big red spikes, they did get easier to manage over time — with some creative biohacks and a few strategic dietary edits.

For example, I have all but removed plant-based milks from my diet (save for a dash of oat milk in coffee; no I have not — will not! — give up coffee entirely. But I do tend to nurse a cup for longer now). The spikes these alt milks served up were just too consistently red flag-ish to ignore and I came to think of them as akin to fruit juice and best avoided. Which — again — is pretty interesting considering how often the marketing of these highly processed beverages makes loud noises about how they offer a ‘healthy choice’.

Interestingly, other Cyborg users seem to have reported a similar issue — per one of the company’s email newsletter round-ups of shared learnings, where it wrote that: “Almond milk and breakfast cereal could actually cause a bigger spike than a hotel breakfast buffet!”

Maybe this is a similar mechanism as can cause a glass of orange juice to spike whereas eating a whole orange (typically) won’t. Or maybe it’s down to something more specific in how these drinks are manufactured — the type of processing they undergo and specific additions. Many have added sugar for instance (although the ones I was pouring on my cereal definitely didn’t — yet they still spiked me). Unfortunately I didn’t have a chance to make a homemade version of oat milk to do a direct comparison with commercial brands to see if it was any less spikey.

For breakfast I do still usually eat a bowl of oats — which certainly also has spike potential (being carbs, albeit fiber-rich carbs) — but I make sure they are jumbo oats (not oatmeal). Most importantly, I liberally dust the bowl with cinnamon (which I discovered helps reduce glucose spikes). And I eat them with water (not any kind of milk), plus a blob of natural yogurt (for flavor and some essential vitamins), plus the usual mix of berries and seeds.

This is not a massive change on my pre-CGM breakfast of choice (oats, berries, seeds etc but washed down with, er, oat milk). But the difference in metabolic score terms? Huge! It switches from a meal that typically scores a ‘2’ to a ‘9’. Crazy but true (or, well, true per Ultrahuman’s reading of my fluctuating interstitial fluids).

I also found creative ways to adapt how I consume bread to limit how much of a spike it generates.

Eating less or even no bread is one way to shrink glycemic load and manage down any associated blood sugar rise. However like oats, wholegrain bread is a complex carb that has dietary benefits so I didn’t want to remove it (or, indeed, quit carbs entirely) from my diet. So, with the benefit of the app’s real-time glucose view, I experimented with eating a slice of wholemeal bread towards the end of lunch, after other fiber, protein and fat rich foodstuffs — which take the body longer to break down — and that seemed helpful.

I then found another specific biohack — involving apple cider vinegar — that worked a treat.

As with cinnamon, I learned this type of fermented vinegar has properties that help to reduce glucose spikes. So I experimented with pouring the vinegar (stay with me) on a slice of sourdough bread before eating it — yes this sounds odd but actually tastes amazing! Using this method, plus eating the bread later on in the meal (after the salad, nuts etc), I could turn a lunch that spiked into one that remained in the healthy zone. There’s simply no way I’d have figured out something as specific as that without being able to see real-time shifts in my blood sugar.

The problem is the lunches that spiked didn’t make me feel any different/less healthy vs the lunches that didn’t. Not without seeing the metabolic response in the app. So it just wouldn’t have been possible to distinguish between them without the sensor data.

Plus, of course, another person, with different metabolic responses, may be able to eat five slices of bread without any spikes at all. So there really is no clever way to generalize — beyond setting basic strictures such as control your carb intake and carefully build the balance of foodstuffs on your plate. And generic, broad-brush strategies that can be very demotivating in the absence of immediate feedback — which is exactly what makes the CGM so potentially, individually transformative as a lifestyle tool. Suddenly you can try stuff and see if it actually works for you or not.

That said, whether managing relatively small blood sugar spikes is as important for a person’s long term health as metabolic tracker startups like to suggest is a wider question.

The TechCrunch reporter as a ‘Cyborg’ (Image credits: Natasha Lomas/TechCrunch)

Dr Matthew Campbell, a scientist who does research into biological systems that impact the human metabolism at the University of Sunderland in the UK, was sceptical about the benefits of otherwise ‘healthy’ people putting so much effort into managing their blood glucose when we asked for his views on this general use of CGM technology.

“Glucose usually fluctuates throughout the day anyway — it’s not a kind of static variable, it is very dynamic. But it should, on average, stay within a normal range. There are cut off points for people who would be characterised as high risk. For example, if your glucose doesn’t come down below a certain level after a meal or in the morning time if it’s chronically elevated. And that’s where the kind of cut points are for diagnosing diabetes or even pre-diabetes, the people who are at risk of developing diabetes,” he tells TechCrunch.

“The issue that we have [with ‘healthy’ people tracking their glucose] is just these arbitrary values — if it’s going down that’s okay, if it’s going up that’s not so good — [but] if you sit within the normal range I don’t know what the clinical utility and the usefulness or the health advantage is of, for example, reducing your glucose by 1mmol if it’s already in the healthy range.

“So I guess if you already sit — 95% of the time — within a healthy range trying to flatten that line or aggressively manage it even lower, I don’t think that confers any additional health benefit because you are already in a healthy range.”

Campbell also pointed to the challenge of correctly linking the blood glucose data that comes from the CGM to everything going on in the user’s body which might be influencing glucose levels, noting too that as well as a time lag the exact position of the sensor on the user’s arm can affect the readings, for example.

“So certain situations, is it your weight, your sex, your ethnicity, individual genetic makeup — all of those different factors influence glucose levels — sleep impacts it, nutrition impacts it,” he says. “And I think if this tech just [tracks] the glucose trace and it doesn’t tie in those other factors then it’s quite difficult to make an informed decision on what is influencing your glucose levels.”

He was more positive about the potential of CGM for athletes, though.

“I think what it can be useful for — you mentioned elite athletes — if you’re exercising at particularly high levels or for a long duration of time — even if you don’t have diabetes, can be at risk of having low blood sugar levels and a lot of this tech tends to come with alerts,” he adds.

Campbell also raised an interesting comparison — suggesting out of range glucose may not always be a problem if the individual’s metabolism is able to aggressively manage it back down again.

“The way to think of it is a little bit like heart rate during exercise,” he says. “If you’re exercising somebody might have a much higher heart rate at the same exercise intensity as somebody else and you might think they’re exercising a lot harder therefore they might be less fit.

“But actually if the variability within the heart rate is a lot greater then that’s more indicative of more cardiovascular flexibility. Which is pretty much associated with very good exercise tolerance and very good levels of fitness — and I don’t really see how it’s any different with glucose response.

“So it’s not necessarily the fact that the glucose level goes outside of range because that happens for a large proportion of people and they can be metabolically healthy — I think what is important is looking at the overall picture.”

Given that, Campbell suggested the true utility of these services will be in augmenting the CGM data with algorithms and machine learning — that can “look for patterns in the data” and “piece things together rather than just cherry picking ‘well your glucose level went high after you did this’; well it doesn’t really matter if it came down fairly aggressively, maybe that’s actually a good thing.”

Returning to blood sugar lows, I had an interesting personal experience in that I was able to figure out — through usage of the app (including by chatting to Ultrahuman’s in-app coaches to get their manual analysis of my CGM data) — that a series of glucose lows I had experienced overnight correlated with waking up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat or even with cramps.

I also noticed that such overnight lows often followed a meal that had involved drinking alcohol (which, turns out, plays its own devilish game of interference with normal metabolic processes). So keeping a careful eye on the ratio of food to alcohol — and perhaps eating a protein-rich snack before bed after an evening meal when I had drunk wine with a less nutrient dense dinner (white rice, say) — was another little hack I was able to work in to shrink the risk of going hypo/crampy in the night without having to forgo wine with a meal.

In that case the personal benefit looks tangible: Not having my sleep unpleasantly disturbed.

I was also able to extrapolate this finding to suggest a similar night time snack hack for an elderly relative — who had been suffering chronic night cramps for months. After she’d adapted her regime to include a strategic bedtime snack she soon reported being almost entirely cramp free overnight.

These are of course just a couple of anecdotal examples — but they are illustrative of the potential for individuals to experiment, make connections and join the dots between the unique quirks of their lifestyle and the CGM data.

Dr Michael Snyder, a Stanford professor and co-author of the aforementioned pioneering research paper — who is also a co-founder of a (rival) US startup, called January AI, which sells its own metabolic health tracking service that’s productizing CGM — is, as you’d expect, evangelic about the benefits of the technology to deliver valuable revelations to individual users.

He actually has Type 2 diabetes — and has worn a CGM to help manage the condition for around a decade at this point — so is well placed to comment on the tech’s utility.

Albeit his personal use, for a specific medical condition, is very different to the general fitness/health use Ultrahuman, January AI and other startups in this space are targeting. But he suggests that broader use of CGM technology could help manage or even reverse the risk of people becoming pre-diabetic or diabetic.

“Right away you learn what foods spike you and what doesn’t — and that just differs from one person to the next,” he tells TechCrunch. “You can actually see people who have glucose dysregulation who might not otherwise know it and this is a big deal because 90% of pre-diabetics don’t know it and 70% of those will go on to become diabetic so one could argue it’s really really valuable to get their glucose under control so at least they can push off becoming diabetic hopefully for a number of years.”

“There’s these kind of hidden secrets in your food — at least they’re secrets to you, they’re probably obvious to somebody,” he adds. “But even people who think they knew everything learn stuff, from what I can tell, that they didn’t realize. And, yeah, there’s just sugar everywhere.

“It probably lines up to the concept that I think now — compared to right after World War 2 — people eat something like 40,000x more sugar than they used to. It’s just everywhere.”

[gallery ids="2253113,2253127,2253114,2253112,2253115"]

“I personally think — from my standpoint — the whole world should be getting measured on this at least on some treatments,” he also tells us. “If your glucose is under control maybe you get measured a little bit less, get measured periodically. But if you’re pre-diabetic or diabetic I think this information should be life-saving on some level.”

Snyder also predicts the tech will get a lot more powerful — thanks to the addition of AI and predictive modelling around food responses based on all the empirical data that’s now being ingested after being fed in by early adopters.

“That’s why you need AI,” he notes. “First of all you’ve got to know which foods spike you — which ones don’t. It’s very empirical unless you just do it you don’t know going in — so we’re finding some people spike to grapes, other people to pasta. Everybody spikes to white rice.

“But different people do spike to different things and at some point we’ll get predictive about what’s doing that but right now it’s just empirical. And so that’s what these devices do — they teach you.”

“For January AI we have food recommender system because we can say well here’s what you’re eating that spikes you and we know the composition of these other foods and with reasonable predictive accuracy we can say well this food didn’t spike you, eat that one, don’t eat that one,” he adds.

“It sounds crazy — but it is a big data problem. You need to have a lot of data and a lot of understanding to be able to do that.”

January AI similarly factors in the user’s activity level — given it also impacts glucose level. And Snyder argues that even just tracking those two elements is enough for such a service to be useful.

“I think that’s essentially at least two of the ingredients — but you’re right there are a lot of factors and that’s why it’s a data problem,” he adds. “Bring in enough data around you personally and we’ve got the data to decide what formulas are working for you.”

Personally, I can say one thing for sure: I have never known a gadget to be so engaging. Just on the pure information level.

The Ultrahuman app’s fairly formulaic alerts — which might pop up to warn you that your glucose is rising and suggest you “get movin'” to bring the level down; or nudge you to eat earlier in the evening for “better sleep quality and metabolic response”; or offer some motivation by trumpeting an “epic/insane start to the day” based on minimal spikes/crashes — were probably the least personally useful element of the product for me. Because, well, if you’re paying attention to the data you’ll soon realize that sort of stuff yourself.

I was very quickly way down the rabbit hole of testing diet/exercise tweaks to see whether I could identify hacks and strategies to keep things frosty green.

It’s absolutely fascinating/terrifying to watch how your body deals with the stuff you throw at it. But, be warned: Your S.O. will hate you as you inexorably whip out your phone at lunch/dinner to first log your meal and then vicariously observe as the app scores your body’s response to whatever you’re eating. It’s a double whammy for screen time. And the stickiest app I’ve used since forever. (Sometimes literally given you’re logging what you’re eating.)

But of course it’s not perfect.

One notable functionality issue I found is that the app wasn’t always able to distinguish between an exercise-related spike (yes intense exercise can raise blood sugar out of the target range!) and a food related spike (even if you’re doing careful logging) — so it could end up scoring your day badly when it shouldn’t.

Exercise spikes are “nothing to worry about”, per Ultrahuman’s coaches — who I quizzed about this via the app’s chat function. “The reason for spikes during strength and HIIT workouts is due to an increase in adrenaline and cortisol which stimulates the liver to break down glycogen into glucose,” was the explanation I got from one of the coaches, along with the reassurance that this is: “Nothing to be worried about. It’s natural phenomenon.”

Now a person with diabetes may need to worry about going out of target even if exercise is the cause — as their body could have trouble bringing the elevated blood glucose back down again. But a person without that diagnosis — the more general consumer that Ultrahuman is targeting for Cyborg — shouldn’t, in theory, be worried.

However the app, in its current form, ended up causing me some concern when I did some intense exercise and then right afterwards ate a meal. High glucose rates caused by the HIIT — which the app will normally notify as “a good spike” — seemed to get co-mingled with the food-related increase and that combination conspired to dent my metabolic score.

Accurately distinguishing a “good spike” from a bad one is evidently a work in progress.

Here’s what Kumar told TechCrunch when we asked about this: “Solving for accuracy of insights that we generate from glucose biomarkers is at the very core of our mission. If we look at clinical grade parameters that determine how one’s body responds to something like food, we get to know that it is a combination of: ‘X ( macro+micro constituent of food ) + Y ( the state of recovery i.e stress, sleep deficit, microbiome diversity etc ).’

“The platform currently looks at X closely and hence you would see that there are many exceptions to how glucose responds to food. With our custom hardware that’s going live in early 2022, we are changing the way we look at this by capturing the rest of the Y factors i.e HRV, sleep etc. We feel this will completely change how we look at the food and activity response and the resulting accuracy.

“For e.g.: The platform will be able to clearly figure the attribution of activity and food within a spike. This is because we could figure out your approximate glycogen release thresholds based on a combination of glucose with other factors that we will capture via our custom hardware wearable.”

Kumar also said the startup is starting clinical trials for a study that relates glucose, insulin and other bodily parameters (“Triglycerides and hormone balance”) to establish what he described as “a proper correlation between glucose monitoring predictions (‘metabolic score’) and the actual state of metabolic health”.

“This has also been attempted in the past with lesser tools and non-continuous glucose at disposal but the v2 here will have way more validation,” he predicts.

So, once again, more research is needed to try to improve the resolution of the ‘personalized’ snapshot of data the CGM is pulling out of your arm. Which also means that these cutting edge quantified health services may still be making a relatively crude assessment of what’s going on in your body at any given moment.

There’s a similar complication with food too of course, unless you’re someone who eats a single foodstuff per meal.

Since most of us eat foods in combination (bundling different ingredients), it’s the combo you’re eating that counts — and, indeed, the order in which you eat different ingredients on your plate can affect how you metabolise them. So the same meal eaten in a different way (or at a different time of day) might go down (or up) differently.

Starting with fiber rich foods (salad, vegetables etc), moving through proteins and fats and ending with (any) carbs — a deconstructed humus salad pita lunch, say — would probably have been less of a low scoring lunch for me than wrapping the same food in bread and eating it the quick and convenient way.

Another clear takeaway from my four weeks as a Cyborg is that fast, ‘convenient’ food — scoffed at a pace — will, inexorably, cause big, unhealthy-looking glucose spikes.

I also found that more processed the food (i.e. prepared meals with added sugars, preservatives, oils etc), were more likely to spike vs eating whole foods, freshly prepared.

This was not surprising to me — I’ve long sought to avoid eating heavily processed foods in favor of stuff I prepare myself using fresh/minimally processed ingredients — but it did underscore how much of a problematic food culture the Western world has developed, with its time-is-money emphasis on speed which encourages liberal use of artificial sweeteners and other additives in order to turn an edible convenience food into a profitable product with a long shelf life.

My experience of using a CGM suggests that eating in a way that is healthier for you — because it generates less inflammation and oxidative stress — requires both more time to prepare food and more time to consume food.

Healthier ingredients may also be more expensive to buy and assemble yourself vs buying a product that comes prepackaged and ‘ready to eat’. So health can literally cost more, in time and money. So there are huge socioeconomic considerations when you start to dig into metabolic health.

Cracking open this Pandora’s (lunch)box has implications that scale beyond our broken food system too — touching on wider structural inequalities baked into our societies.

Poor health and poverty are often intertwined. And it remains to be seen whether big data and AI will be able to break that link by democratizing access to valuable health insights — scaling broad utility off of enough individual-level learnings — or whether tech’s wealth divide will just serve to further accelerate inequalities as health tech gets smarter too.

The concept of a cyborg instantly implies a new elite tier of humanity. But what about all those who can’t afford to be wired in?

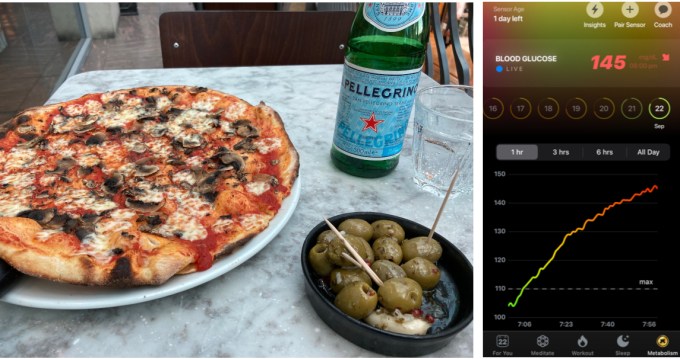

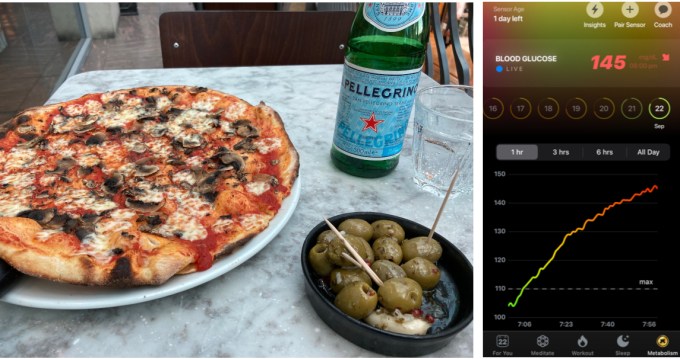

Pizza for dinner? A slow but steady rise in blood sugar may follow… (Image credits: Natasha Lomas/TechCrunch)

Verdict & Price

While I remain (healthily) sceptical of the scale of the potential gains being claimed for metabolic tracking, four weeks as an Ultrahuman Cyborg was long enough to convince me this is the start of something big. And I didn’t have an obvious need going into testing the product — such as wanting to lose weight or needing to get fit. I’m just interested in staying healthy.

Nor am I a big fan of fitness wearables, generally. But this felt like a different level of self quantification.

The future of healthcare will certainly be about shifting towards preventative interventions by leveraging data accessibility to inform and augment our ideas about what’s good and healthy for us — even if, where metabolic health is concerned, there’s no shortage of learning and research still to do.

The data from individual sensors (Ultrahuman’s service alone has some 400x cyborgs at the time of writing) will also feed research that will continue to deepen our understanding of complex metabolic processes. Although there is a degree of risk that commercial interests will look for results which support and underscore their point of view, the potential scale of use — as more of these services launch — should help drive transparency and keep the science clean.

At the same time there is plenty to be cautious about.

The most engaged and scientifically literate users are likely to get the most out of this sort of tracking as they can bring wider knowledge/resources to bear to help them interpret their data — while a less informed user might take an overly simplistic read of what the information means.

There is also the risk that linking big bold stress triggers to food and other lifestyle events could lead to (or exacerbate) problems like eating disorders. The service wrapper and support are therefore a really key piece of making the most of what CGM tech can offer.

In short, poor UX decisions could have serious ramifications. And a lot of care and due diligence is needed over service design and delivery.

Longer term, having a snapshot view of blood glucose may — on its own — turn out to be far too limiting.

A more fully integrated tracking platform is likely to be needed to deliver the best understanding of an individual’s metabolism, drawing in a variety of signals and biomarkers. Although, right now, tracking glucose feels like a start; one which offers the chance to experiment with lifestyle tweaks that could accrue significant benefits over time — in a way that’s far more motivating than trying to figure out healthy individual dietary choices without any kind of real-time feedback.

Even just four weeks using the product yielded so many interesting tidbits and so much food for thought — avocado and egg is a super solid breakfast choice!; beer is a terrible spiker but natural cider looks (er) practically medicinal!; olives and nuts are truly the food of the Gods! — and the experience has led me to make some small but sustained lifestyle changes.

The jury is still out on whether those tweaks are genuinely worthwhile from a long-term health point of view. But given the changes weren’t especially radical, even if there’s only a tiny chance they have a benefit then, really, where’s the harm in that?

That said, another qualification: I do wonder whether (further) reducing the amount of carbs I eat — as a result of seeing how much they can spike me — might not have capped how much energy I have available for training purposes.

I already had a fairly low intake of carbs and it’s important to remember that food is also fuel — and energy needs vary. So a ‘spikes are bad, stability is best’ view on blood glucose may be too simplistic for an above average sporty lifestyle.

There is a real need to plug this data into relevant specialisms. A personal trainer would likely be able to make far more intelligent use of my results for me — based on knowing my individual fuel for training needs. Such a person may even be able to advise on dietary tweaks that could let me have my bread and eat it, so to speak.

But of course a personal trainer — or nutritionist — isn’t something everyone can afford or otherwise justify based on their (non-Olympic athlete) lifestyle. So on that front the product looks good value. (Even if you’re mostly getting raw data and need to do much of the wider interpretation yourself.)

How much does Ultrahuman’s Cyborg cost? The beta program is priced at ~$80 for two weeks (or $470 for 12 weeks). If you were paying a human personal trainer to be on your case and analyzing your data 24/7 it would be a lot more expensive than that — so it looks like pretty good value. (A decent personal trainer might cost $80 an hour.)

It’s important to emphasize that the app isn’t actively trying to be a full-time personal trainer. But it can do some basic things like offer exercise nudges if your blood glucose gets too high and — retrospectively — identify your “best workout zones”, aka optimal time windows to take exercise over the course a week based on how your body was fuelled. (“Do you see a trend? Use these times to your advantage to crush your next workout” was one suggestion it emailed me, although this nudge seemed more random than useful tbh.)

There are also a few (human) coaches on hand in the app to take questions and help you analyze your data. Plus you can always ask for help from other users via the invite-only Cyborg Slack channels. (Albeit, that’s crowdsourced wisdom, not dedicated professional support.) So the ‘relative value’ price-tag comes with the caveat that most of the time you’re on your own when it comes to drilling in and distilling more nuanced insights.

One more thought to ponder: As with every data-driven and ambitiously predictive AI product the Cyborg isn’t just training you; your data is training the Cyborg… So how much do you think 24/7 access to your biology is worth?

The value being derived from your highly intimate personal data flows two ways — and that upside isn’t necessarily being distributed equally. If you feel you’re getting enough value from the service that may not bother you. But privacy considerations are impossible to ignore.

Even if you’re comfortable sharing such intimate data with a commercial company in order to be able to access the service, Ultrahuman’s privacy policy for Cyborg notes some circumstances where your information may end up elsewhere — such as if it receives a subpoena it’s legally bound to respond to.

The policy also specifies that: “Anonymized, aggregated data may be shared with advertisers, research firms and other partners.” And robustly anonymizing health data has been shown to be notoriously difficult to do, even as the adtech industry has shown a rapacious appetite for triangulating and “sharing” data to better profile individuals for targeting — up to and including applying labels like “diabetes”. So your highly personal data leeching from a CGM into the modern web’s manipulative microtargeting ad matrix is not, unfortunately, impossible to imagine.

But let’s end on a personal note: What has Kumar himself learned from using CGM to track his glucose?

“For me the biggest learning has been around expanding my food spectrum and incorporating more of the foods that I like. Prior to this I pretty much followed a disciplined diet but couldn’t sustain it for long given it would affect social eating etc. With Cyborg, I’m able to understand how I can balance food with my activity. On the days I lift weights or am generally more active, I know that I have a little bit of extra flexibility around eating what I want to,” he tells TechCrunch.

“The other big learning — which is a work in progress — is around maintaining stable energy levels throughout the day. For me, stable glucose levels are broadly correlated to stable energy levels and this is what I’ve been trying to maintain during a particular week where I have a lot of reading work to do.”

Cutting edge competition

Here, past the quantified self trend’s needle-phobia line, is truly a wild(er) west — a lesser trodden arena of experimental startup opportunity. Naturally, it’s a lot more interesting than boring old step/sleep tracking, exactly because it’s so much less familiar.

There is a genuine sense of discovery as you fire the spring-loaded CGM sensor into your arm; feeling like a bit of a pioneer, involved in a kind of citizen science collective — with the fascinating opportunity to design and run experiments that interrogate the health of your own lifestyle.

On top of that, is the overarching possibility that what you learn personally might be useful to others — encouraged by Ultrahuman’s community-building efforts around Cyborg (such as its Slack channels, where early adopters are encouraged to share their learnings; as well as virtual and in person meet ups) — so there’s a ‘philanthropic mission’ feel as well.

Startups that are bold enough to get entangled in skin-puncturing machine-human interactions do have a chance to stand out. After all, mainstream tech giants simply can’t be that freaky. And it sets them apart from the wider wellness quantification crowd that’s plumped for a more quotidian biomarker to track.

That in turn means these startups have a chance to grab some very intimate biological data to feed their product dev, data science, AI models and algorithmic predictions; and — potentially — jockey themselves into position to race ahead as consumer appetite for personalized health services steps up.

On the blood glucose tracking front — an activity that has traditionally been associated with people who have conditions like diabetes (or pre-diabetes) — a large number of startups are now taking the plunge into willing recipients’ interstitial fluids.

As well as (India’s) Ultrahuman, with its still beta Cyborg service, there’s January AI, which does glucose tracking combined with heart rate monitor data to offer personalized food predictions and exercise ‘recipes’ to help you burn off any indulgent excess; Levels Heath, which has bagged backing from a16z; Signos, which is using CGMs to offer real-time weight loss advice; the athletic-performance focused Supersapiens; and NutriSense, which offers big picture soundbites around “optimizing” your “daily health performance”, to name a few of Ultrahuman’s US CGM-leveraging rivals.

There are more competitors in Europe — including (UK-based) Zoe, which is using data from large-scale microbiome studies to generate AI models to predict individual food responses. So as well as getting users to wear a blood glucose monitor, it also asks them to send in stool samples for lab analysis.

Also targeting glucose monitoring in the region is Germany’s Perfood (“personalized diet” for weight management); and Holland’s Clear Nutrition (“learn your unique responses to food” and “build your own nutrition plan”). At the time of writing, another European company in this nascent space, Finland’s Veristable — or Veri for short — was spotted advertising its 24/7 glucose monitor service on photo-sharing social network Instagram.

The ad pictured a very hipster look model sporting the same disc-shaped wearable which Ultrahuman’s service uses (and indeed many others do), taped over with a stylish grey patch vs the former’s black and white disk emblazoned with its tipped ‘K’ symbol. “End the Guessing Game of “What Should I Eat?” Veristable’s ad proclaimed, pointing Europeans toward a €159pm service.

Both Veri, which raised a seed round in June (per Crunchbase), and Ultrahuman — and a number of others — are using a CGM made by Abbott (the aforementioned FreeStyle Libre). This disc-shaped data-collecting device comes with a spring-loaded applicator that’s armed with a hollow needle. Once positioned in place you press down (firmly but not too firmly) and it fires the filament directly into your flesh.

The novelty here isn’t the tech itself — CGMs have been around for some years (Abbott’s FreeStyle Libre was introduced in 2016 for example, while Dexcom, another maker, got FDA approval for a fully interoperable CGM that could be used with other electronic diabetes management devices back in 2018) — it’s what they’re doing with it that’s experimental.

So while CGM tech has already been a transformative technology for people with diabetes and pre-diabetes, it’s only relatively recently there have been moves to commercialize it for a more general user who just wants to get to know their own body better.

Last summer, Dexcon gained FDA clearance for its real-time APIs for third party developers and devices. Fitness hardware maker Garmin was among the first wave of companies signed up to work with it to expand users’ access to their glucose data, albeit still with a focus on boosting utility for people with diabetes.

But investors have been quick to spot broader consumer potential — and are increasingly injecting funds to accelerate developments and get CGMs into many more arms.

Early last year, for example, January AI topped up with a further $8.8M; while Zoe bagged a $53M Series B in May 2021 (recently expanded when they added Balderton as an investor). Ultrahuman also announced a $17.5M in Series B (in August 2021); while Signos raised a $13M Series A in November.

As more data flows, it’s a safe bet that much more VC cash will follow.

Ultrahuman’s PR points to the scale of the addressable potential market — talking about an emerging “metabolic health crisis”, and claiming that some 88%+ of Americans (and almost 80% of the global population) are “dealing with a metabolic disorder”; and thus could potentially benefit from joining its “Cyborg army”, as it brands early adopters.

So the potential addressable market is huge. Although any such wider onboarding looks like it will entail a steep learning curve — as startups seek to push beyond the low friction pond of early adopters and performance enthusiasts and step outside the quantified self and biohacking communities where this tech will naturally thrive.

A big part of Ultrahuman’s community-building efforts focus on encouraging users to share individual experiences and tips via invite-only Cyborg Slack channels and Townhalls, as well as signing up sporty influencers to evangelise the benefits of “performance fuelling” and other biohacking techniques that feed the purpose of sporting a CGM.

“The world currently has over 500M+ people who are diabetic but if you look at the problem holistically, you’d notice that there are almost 600M+ pre-diabetic people,” its PR goes on to claim, before suggesting the cure: CGM technology combined with “health score algorithms” and “instant health nudges” — which it argues “could help millions improve and help control / reverse this crisis”.

Whether millions of people can be sold on wearing a sensor in their skin remains to be seen.

But the technology may well evolve so it can be less invasive — and more mainstream-friendly — without losing too much accuracy. At which point there’s no reason to think it wouldn’t become a standard bit of fitness kit.

Whether a metabolic tracker subscription service is something millions of people will shell out for every month is another question. But once you’ve had a taster of this kind of data access it can be addictive. Even if you may also feel a bit ‘watched’ and judged as the sensor feeds back data on your lifestyle choices and the software scores how healthily you live.

It’s funny to imagine that the world’s unhealthy pursuit of something sweet to eat may, over time, get commercially rerouted into tracking and biohacking the rollercoaster ride of blood sugar — which should at least be a healthier fixation than blindly chasing the next sugar high.