Can carbon credits for improving forests help save them — and us — from climate change?

Rising pressure on big business to address the threat of climate change by decarbonizing their ops has, in recent years, led to huge demand for carbon offset schemes — enabling companies to buy carbon credits to ‘offset’ emissions so they can claim to be ‘greening’ their activities, without having to make more substantial changes (like, say, an airline running fewer planes).

Unsurprisingly this has created lots of wonky incentives attached to forestry resources and carbon offsetting projects. Which, in turn, is creating lots of knock-on startup opportunities.

One example of dubious carbon offsetting involves existing woodlands being repurposed for carbon credits in a way that artificially inflates the claimed credit — such as by claiming a forest was going to be cut down when it wasn’t, meaning there is no net increase in carbon sequestered (and a woodland is essentially just repurposed to help corporates greenwash their pollutive ‘business as usual’). So without robust oversight carbon offsetting projects can clearly be a sink for kicking the climate can down the road towards disaster.

Similarly, greenwashing pressures have led to the awful sight of trees being chopped up for biomass and burnt — under a dubious claim of ‘green energy’. Here, too, there’s a need for rigorous accountancy — in the form of a full lifecycle analysis of a biomass project — else the risks can even go beyond meaningless greenwashing to actively harmful environmental outcomes (such as a loss of mature woodlands and another net reduction in how much carbon is sequestered).

Pressure on companies to quickly get on a path to carbon neutrality is, very evidently, generating huge but often poorly directed demand to stand up glossy marketing pledges that claim to be ‘tackling’ climate change.

The overarching question is whether anything of value is being done with this corporate reputation spend when it comes to actually preventing catastrophic climate change?

Turns out this too is a burgeoning startup business opportunity.

Startups applying technologies to target the accountability/credibility gap around carbon offsetting by proposing schemes to verify the credibility of projects and monitor performance include the likes of Pachama and Sylvera, which are both backed by some major investors — with around $25M and $39M raised respectively to date.

There are also startups focused on expanding access to carbon markets so that smaller landowners can get looped into revenue-generating carbon offsets for their woodlands. Such as US-focused Silvia Terra.

The prospect of receiving recurring revenue for conserving forestry may at least held protect woodlands from other forms of development that could see trees felled to make way for different money-generating schemes with less or no carbon sequestering benefits. But — clearly — forestry conservation alone isn’t going to be enough to reduce global carbon emissions.

Hence other climate startups are focused on expanding the volume of forested landmass. Such as Terraformation — which is using a mix of old and new technologies to rapidly reforest wasteland with the goal of increasing the amount of global landmass that’s covered by trees.

Again, though, even tree planting has been criticized as a flawed “magical thinking” non-solution to climate change.

In some cases, poor incentives to simply increase forestry volume have led to native tree species being ripped out and replaced with faster growing alternatives — leading to biodiversity loss and a forestry monoculture that’s less resilient to the challenges of a changing climate. Which is also, ultimately, environmentally counterproductive.

Climate change increases the risk of drought, storms and forest fire — all of which can decimate forests. So mindless tree planting projects that fail to effectively model risks, don’t selectively and sensitivity plant, and fail to follow through with good forestry management to ensure the long term success of a woodland are also best filed under pointless (and even potentially harmful) greenwashing.

The sad truth is that, globally, forests are still being felled at a far faster rate than they’re being replanted — and ultimately that net destruction is fuelled by the unreconstructed demands of industry and the system of growth-focused consumption that powers the modern world.

Without systemic restructuring of how we consume and trade towards a reformed, circular economy that revolves around reuse and longevity it’s hard to see how the rapacious global engine of demand can be dialled back to an environmentally sustainable level — in which trees and all the rest of life on Earth (including humans) can survive and thrive far into the future.

Given such vast challenges — not to mention the incremental timescales involve in anything attached to forestry ecosystems — startups that are trying to make a meaningful difference in this space certainly have their work cut out.

Optimizing for forest survival

YC-backed Pina Earth is a relative newcomer (founded 2021) that’s trying to tackle some of the problematic incentives around carbon offsetting projects by creating smarter skews that encourage landowners to increase woodland biodiversity and future-proof forests against the hotter, harsher climate that’s fast coming at us.

It’s doing this by pitching forest owners on making sustainable improvements to existing woodlands that will enable them to get certification for additional carbon credits — i.e. on top of whatever their woodland may already be bringing in — generating a “recurring income” via selling any extra stored carbon to the scores of companies eager to top up their offsetting.

So while some carbon offsetting atop existing woodlands may be accused of bogus greenwashing, here at least the premise is that carbon credits are being attached to — and contingent on — improvements to forestry that will, or well, should generate extra carbon, assuming all goes to plan.

“With the help of sustainable forestry, your forest can store additional carbon,” runs the pitch to forest owners on Pina Earth’s website. “This is done through measures such as planting climate-resilient tree species and increasing biodiversity.”

The Munch-based startup — which is backed by Y Combinator — was set up by a trio of founders, CEO Dr. Gesa Biermann; CPO Florian Fincke; and CTO Jonas Kerber who met at the Center for Digital Technology and Management (CDTM) and have a collective background in environmental studies, human-computer interaction, robotics and technology management.

Munich startup Pina Earth’s co-founders; L to R: Fincke, Biermann, Kerber (Image credits: Pina Earth)

Their idea is to sell landowners on the financial value of good woodland management — linking sustainable forestry to additional carbon credits which mean there’s a financial reward for making the kinds of relatively costly interventions that are likely to be needed to make woodlands more productive (in carbon sequestering terms) and resilient to climate change over the longer term.

“Essentially we’re building an online platform where we’re connecting forest owners and carbon credit buyers,” explains Biermann. “Our goal is to make it as easy as possible for forest owners to be rewarded for the ecosystem services they provide.”

“In the projects that we do we’re trying to change the species diversity of the forest over time to make it more resilient to climate change,” she adds.

“That’s really our goal — to democratize access to this market, to the voluntary carbon market in this case, where I think for one of the first times you’re able to align ecology and economy in a very productive way,” she also tells TechCrunch. “The way that it works in the forest timeline is you actually give out future-looking carbon credits — this is quite common in the forestry carbon credit scene because they’re just slow ecosystems. So you’re trying to overcome this by paying someone now for the carbon that will be sequestered a bit later on.

“With the monitoring cycle that we have of about three years this is something that we would then align to these vintages of carbon credits being given out in three year cycles to keep incentivizing the forest owners to keep doing the restructuring project over time.”

Albeit she won’t be drawn into predicting exactly how much extra income a landowner might be able to generate through additional carbon credits. (She says the price will “depend” on a variety of per-project factors, such as the existing tree species and how much optimization is possible.)

“That’s kind of the challenge we’re trying to address the whole way through is incentivizing someone to do something now that will pay off in let’s say 30 or 40 years because forests are just very slow ecosystems,” she adds. “As a startup I think that’s quite an interesting challenge because us starting into this journey — the effects of this will take place a lot later, so once we are kind of close to the end of our work life, so I think that’s a very interesting perspective on the timeframe, also as a startup founder.”

To support its long term environmental mission, Pina Earth is building a platform that helps landowners with the admin side of project certification, especially to make it easier for smaller landowners to access carbon markers — while also taking care of the remote sensing and AI modelling to quantify a project’s carbon outputs and — it hopes — increase the speed and quality of carbon credits derived from the forestry.

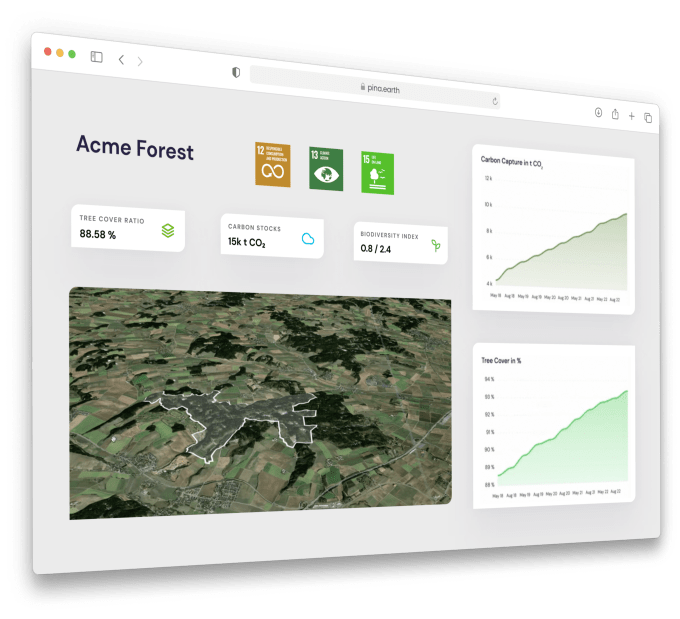

There are a couple of components to Pina Earth’s product (which is still pre-commercial launch).

Firstly process automation: It’s building out a platform to support landowners through what can be a complex certification process vs manually filling in scores of forms.

Pina Earth project dashboard (Image credit: Pina Earth)

The second, back-end element involves complex data processing and modelling, such as using machine learning to predict how climate change might affect future growth of the forest and impact its ability to sequester carbon.

To power this and conduct ongoing remote monitoring of the projects Pina Earth is pulling in and processing 2D and 3D data on forests, captured via sensors attached to ultralight aircraft (it partners with a third party to do the actual data gathering).

She says they considered a range of possible methods for remotely capturing data to monitor the carbon offsetting projects — from drones to satellites — but settled on hobby planes as best suited to capture the level of data needed for it to be able to quantify improvements to forests.

“We’re in the middle with this approach of using ultralight aircraft data because the type of project that we’re focusing on — improved forest management — actually requires an improved resolution [vs satellite data] to be able to detect the tree species,” she notes.

“Our goal — with these improved forest management projects — is we try to summate into the future what will happen to this particular forest under climate change. Because especially in Germany — but also throughout Europe — we’ve been seeing a lot of forests dying due to droughts, bark beetles, storms. And we’re trying to incentivize forest owners to change the structure of these forests that are mostly monocultures — usually one type of tree species — to a biodiverse mix.”

Biermann likens the approach to diversifying a financial portfolio — i.e. in order to make it “less prone to risk in the future”.

As well as increasing the mix of of trees in a woodland as a strategy to reduce disease risk, she mentions that having forestry where growth is managed so as not to have all the trees at the same height can help with resilience to storms, for example.

She suggests it may also be the case that landowners need to plant different, even non-local tree species that may be more resistant to the hotter temperatures and drought conditions which are associated with climate change.

Per Biermann, Pina Earth is planning to do monitoring of projects about every three years — “to have a tighter net on what’s going on on the ground in this forest; is it developing in the way we’d like it to?”, as she puts it.

Doing remote monitoring of forests allows for more regular monitoring vs traditional on the ground methods, which — she suggests — helps improve the quality of the carbon credit. She says its method is able to transform the 2D and 3D forestry data it gets as a raw input into “single tree-based carbon storage” validation of projects.

“I think what’s also unique in our approach is that we simulate carbon sequestration of every single tree that we detected into the future under changing regional climate conditions,” she adds. “This allows us to optimize for this forest’s survival probability and sequester more carbon. So I think there’s where we have a unique twist to forest carbon projects because we’re very much focused on making those forests climate resilient.”

While the startup’s initial business model is focused on charging forest owners for its SaaS, Biermann says ultimately they want to be able to offer the tech for free to maximize access — but would then charge a cut on any extra carbon credits generated.

However that could create a potential conflict of interest — since Pina Earth is also involved in assessing the quality and performance of the projects.

Asked how it would resolve that conflict Biermann says it’s working with a German non-profit — which has a technical advisory board that spans environmental organizations, forestry science and the carbon credit market — and she envisages such an independent entity being involved in helping to verify the carbon credits as an additional accountability layer.

“We’re partnering with this local non-profit that’s developing a domestic German forest carbon standard,” she says, adding. “Since they are also just developing this we’re working very closely to get our data interactions points very aligned so that there won’t be the downside of having larger costs and having a longer process to get certified… In this case working with this non-profit that’s also doing the stakeholder consultation really gives this additional trust and allows us to not have this conflict of interest because there’s another party also looking at the project.”

Discussing generally how it stands up the accuracy of its data, she says it’s using terrestrial forest data (which landowners usually already have) at the start of a project to benchmark the accuracy of its models when it’s using remote sensing.

“This ground-truthing with terrestrial data’s really important to use to be able to show we can get close to these results,” she says, adding: “The other side of it, I think, is more related to having a stakeholder dialogue — to get everybody on board, all kinds of different organizations, because you have to agree on the way a forest carbon credit is actually generated, and for that we’re partnering with [local] organizations.”

Biermann says Pina Earth is also intending to put its method through a public consultation process — and its website notes that its open data approach will include purchased carbon credits being “retired in a public registry” to ensure they can only be used once — “to make sure that we don’t have any blind spots”.

Given the rising numbers of carbon offsetting validation startups there are likely to be growing opportunities for other types of partnerships that may further help drive accountability.

“I think that’s actually one of the most exciting things of working in this particular segment because at least from our experience everybody is so open to partnering because the bottom line is you’re trying to remove carbon from the atmosphere and you’re trying to create this sustainable impact so if we could achieve this by partnering I think everybody is kind of on board, so there’s usually not a long discussion on this,” adds Biermann. “It’s much more collaborative, I think, than other environments.”

What about if forest projects don’t perform as it projected when it handed out the carbon credit?

On that, Biermann says it’s built in multiple safeguards — starting with making conservative assumptions on the science side.

It is also structuring the credit system with a “risk buffer”, whereby a certain percentage of carbon credits are pooled across all projects, so aren’t given out, “as an internal insurance mechanism”.

“We are also doing this frequent monitoring cycle because we want to be able to incorporate new science as it comes out,” she adds. “Thankfully this is a really active science scene and we are quite close to the scientific community un our startup so also with our measurements and monitoring we want to adjust to and adapt to whenever anything new is found out… to really guarantee this high quality carbon credit, also for the carbon credit buyer side.”

On the wider critique of carbon offsetting — i.e. that it generates greenwashing by creating a means for companies to pay to avoid making systemic changes that will lead to net reductions in their own carbon emissions — Biermann agrees this can be a problem.

“Some carbon credits projects have been questioned on the way they set up their methodology and that’s why we went through all of the forest methodologies that are out there for domestic and international standards for voluntary carbon projects to rethink the criteria and to try to automate the documentation to, again, democratize access to these but also to really think about what does a high credit have to show? What’s important to do in terms of data?” she also says.

To try to avoid Pina Earth ending up inadvertently working for greenwashers, Biermann says it’s partnering with organizations that are doing carbon footprinting for corporates.

“Partnering with them I think is important because then they’re the part who does the footprint calculation, according to official criteria. They first work on reduction methods and only then do they resort to offset projects. So I see ourselves very much in this chain — and the important of other partners who work on footprinting and reduction,” she suggests.

“There are so many startups working on different issues — let’s say of the carbon credit value chain — I can think of a lot of other problem areas where it would be great if other startups started; having a way to really tell the footprint of a company through the scope 1, 2, 3 [emissions]. Being able to make that transparent. Yeah, so a lot of transparency issues along the value chain are being tackled by different startups… And those are the ones we get to partner with, essentially.”

On the go to market front, Pina Earth is focused initially on its home turf and forests of Germany — where it is currently operating two projects across 1,200 hectares as it prepares to launch later this year.

But Biermann says it believes its approach can scale across Europe — and she mentions France, Spain as other countries of “particular” interest, because they have quite similar forest structures to Germany so it reckons it could easily transfer its methods there.

The UK is another potential market it’s eyeing expanding into, she adds.

“An advantage with these countries is they already have domestic forest carbon standards — in the UK that would be the woodland carbon code for example,” she notes. “And we could then apply to get our methodology approved with them to develop these types of improved forest management projects under a domestic standard in a different country.”

Sadly, a study published in 2020 found that Europe’s forest biomass has seen a dramatic rise in the rate of loss since 2015 — likely as a result of increased demand for timber and to burn wood for biomass. So the trend curve is not bending in the right direction.

Albeit that means there’s even greater imperative to nudge regional landowners towards sustainable forestry and caring for — not cutting down — their precious woodlands.

What’s Biermann prediction for the future of forestry? Is every woodland going to be end up under some form of high tech surveillance and carbon quantification — with such tech becoming a key conservation tool, given the still rising pressures on natural ecosystems?

“It comes back to if you don’t really measure it you can’t really incentivize it and you can’t really value it,” she says. “At least in the way that our economy works. So I think it would be really beneficial for forests to be measured more closely and to then brought to the attention of the public and investors.

“I think we can see a shift towards this — I think it goes beyond climate investments being done for the climate’s sake but because it is the next wave of innovation and economic opportunity. So I think in that sense these monitoring systems will become more applicable to also other forest areas.”

Currently Pina Earth is in YC’s Winter batch — so is focused on getting ready for demo day.

The $500k in funding it’s received via the accelerator is its first external investment, with the founders having bootstrapped early research and development of the product.

“We had a couple of grants that helped us bootstrap along the way and this is the first equity funding now that we’ve gotten. We’re looking to use the money to hire key team members… and to launch the product on the market later [this year].”

“Right now we’re really focused on product development and getting that off the ground and running,” she adds. “So trying to take also the advice — by YC — to heart to really collaborate with our customers as much as possible.”