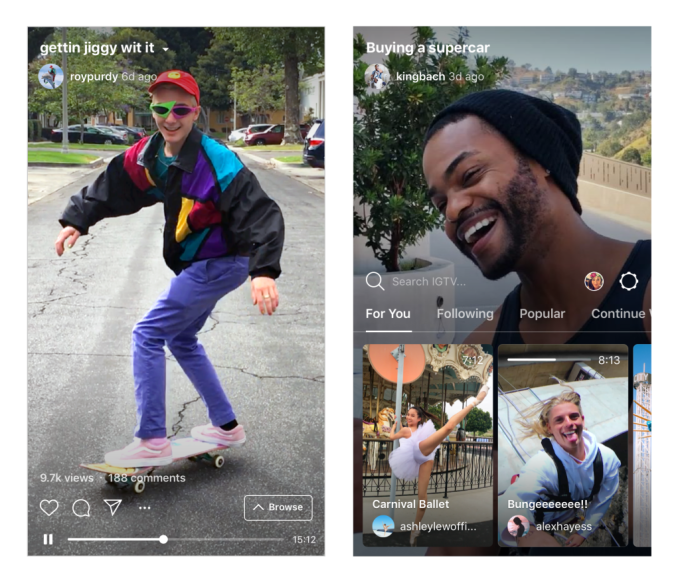

Instagram has never truly failed at anything, but judging by modest initial view counts, IGTV could get stuck with a reputation as an abandoned theater if the company isn’t careful. It’s no flop, but the long-form video hub certainly isn’t an instant hit like Instagram Stories. Two months after that launched in 2016, Instagram was happy to trumpet how its Snapchat clone had hit 100 million users. Yet two months after IGTV’s launch, the Facebook subsidiary has been silent on its traction.

“It’s a new format. It’s different. We have to wait for people to adopt it and that takes time,” Instagram CEO Kevin Systrom told me. “Think of it this way: we just invested in a startup called IGTV, but it’s small, and it’s like Instagram was ‘early days.'”

It’s indeed too early for a scientific analysis, and Instagram’s feed has been around since 2010, so it’s obviously not a fair comparison, but we took a look at the IGTV view counts of some of the feature’s launch partner creators. Across six of those creators, their recent feed videos are getting roughly 6.8X as many views as their IGTV posts. If IGTV’s launch partners that benefited from early access and guidance aren’t doing so hot, it means there’s likely no free view count bonanza in store from other creators or regular users.

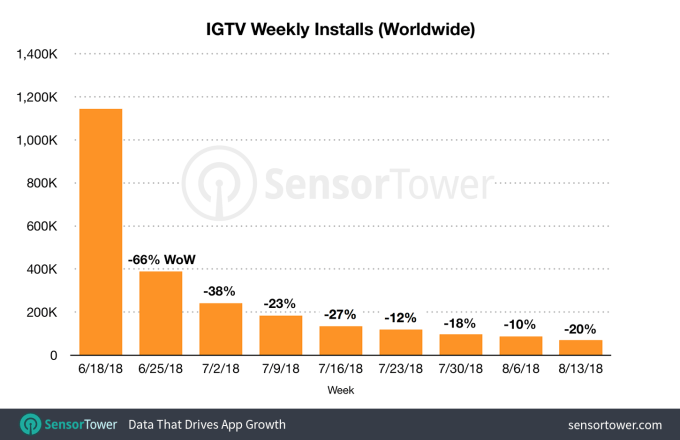

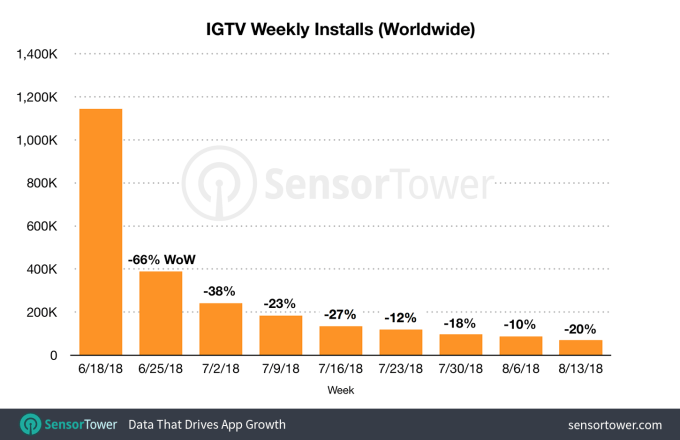

They, and IGTV, will have to work for their audience. That’s already proving difficult for the standalone IGTV app. Though it peaked at the #25 overall US iPhone app and has seen 2.5 million downloads across iOS and Android according to Sensor Tower, it’s since dropped to #1497 and seen a 94 percent decrease in weekly installs to just 70,000 last week.

Instagram will have to be in it for the long haul if it wants to win at long-form video. Entering the market 13 years after YouTube with a vertical format no one’s quite sure what to do with, IGTV must play the tortoise. If it can avoid getting scrapped or buried, and offer the right incentives and flexibility to creators, IGTV could deliver the spontaneous video viewing experience Instagram lacks. Otherwise, IGTV risks becoming the next Google Plus — a ghost town inside an otherwise thriving product ecosystem.

A glitzy, glitchy start

Instagram gave IGTV a red carpet premiere June 20th in hopes of making it look like the new digital hotspot. The San Francisco launch event offered attendees several types of avocado toast, spa water and ‘Gram-worthy portrait backdrops reminiscent of the Color Factory or Museum of Ice Cream. Instagram hadn’t held a flashy press event since the 2013 launch of video sharing, so it pulled out all the stops. Balloon sculptures lined the entrance to a massive warehouse packed with social media stars and ad execs shouting to each other over the din of the DJ.

But things were rocky from the start. Leaks led TechCrunch to report on the IGTV name and details in the preceding weeks. Technical difficulties with Systrom’s presentation pushed back the start, but not the rollout of IGTV’s code. Tipster Jane Manchun Wong sent TechCrunch screenshots of the new app and features a half hour before it was announced, and Instagram’s own Business Blog jumped the gun by posting details of the launch. The web already knew how IGTV would let people upload vertical videos up to an hour long and browse them through categories like “Popular” and “For You” by the time Systrom took the stage.

IGTV’s launch event featured Instagram-themed donuts and elaborate portrait backdrops. Images via Vicki’s Donuts and Mai Lanpham

“What I’m most proud of is that Instagram took a stand and tried a brand new thing that is frankly hard to pull off. Full-screen vertical video that’s mobile only. That doesn’t exist anywhere else,” Systrom tells me. It was indeed ambitious. Creators were already comfortable making short-form vertical Snapchat Stories by the time Instagram launched its own version. IGTV would have to start from scratch.

Systrom sees the steep learning curve as a differentiator, though. “One of the things I like most about the new format is that it’s actually fairly difficult to just take videos that exist online and simply repost them. That’s not true in feed. That basically forces everyone to create new stuff,” Systrom tells me. “It’s not to say that there isn’t other stuff on there but in general it incentivizes people to produce new things from scratch. And that’s really what we’re looking for. Even if the volume of that stuff at the beginning is smaller than what you might see on the popular page [of Instagram Explore].”

Instagram CEO Kevin Systrom unveils IGTV at the glitzy June 20th launch event

Instagram forced creators to adopt this proprietary format. But it forget to train Stories stars how to entertain us for five or 15 minutes, not 15 seconds, or convince landscape YouTube moguls to purposefully shoot or crop their clips for the way we normally hold our phones.

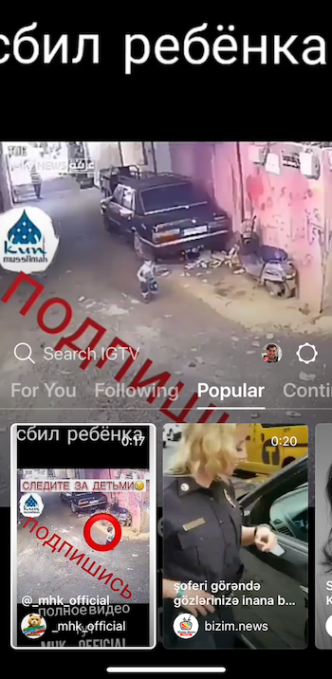

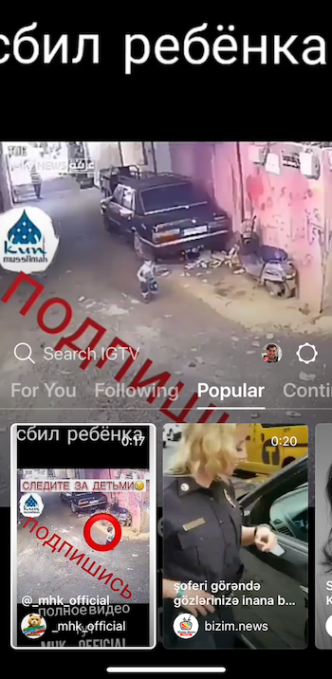

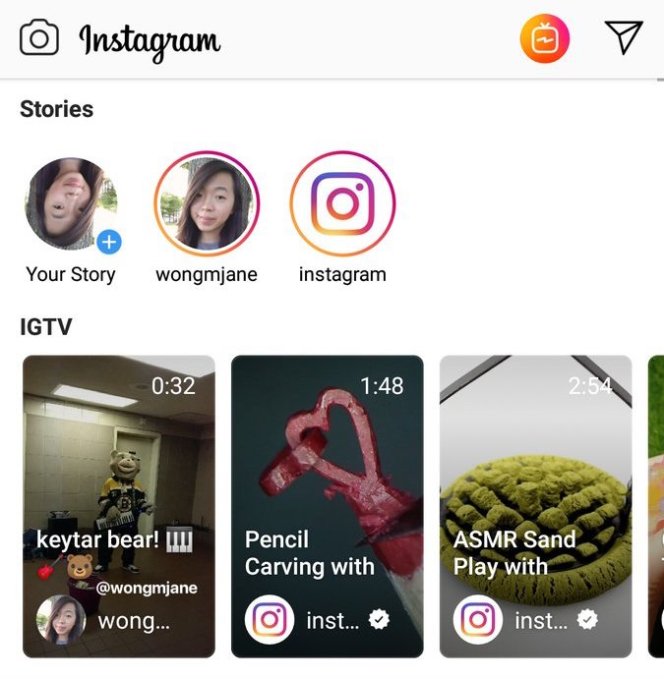

IGTV’s Popular page features plenty of random viral pap, foreign language content, and poor cropping

That should have been the real purpose of the launch party — demonstrating a variety of ways to turn these format constraints or lack thereof into unique content. Vertical video frames people better than places, and the length allows sustained eye-to-lens contacts that can engender an emotional connection. But a shallow array of initial content and too much confidence that creators would figure it out on their own deprived IGTV of emergent norms that other videographers could emulate to wet their feet.

Now IGTV feels haphazard, with trashy viral videos and miscropped ports amongst its Popular section alongside a few creators trying to produce made-for-IGTV talk shows and cooking tutorials. It’s yet to have its breakout “Chewbacca Mom” or “Rubberbanded Watermelon” blockbuster like Facebook Live. Even an interview with mega celeb Kylie Jenner only had 11,000 views.

Instagram wants to put the focus on the author, not the individual works of art. “Because we don’t have full text search and you can’t just search any random thing, it’s about the creators” Systrom explains. “I think that at its base level that it’s personality driven and creator driven means that you’re going to get really unique content that you won’t find anywhere else and that’s the goal.”

Yet being unique requires extra effort that creators might not invest if they’re unsure of the payoff in either reach or revenue. Michael Sayman, formerly Facebook’s youngest employee who was hired at age 17 to build apps for teens and who now works for Google, summed it up saying: “Many times in my own career, I’ve tried to make something with a unique spin or a special twist because I felt that’s the only way I could make my product stand out from the crowd, only to realize that it was those very twists and spins that made my products feel out of place and confusing to users. Sometimes, the best product is one that doesn’t create any new twists, but rather perfects and builds on top of what has been proven to already be extremely successful.”

A fraction of feed views

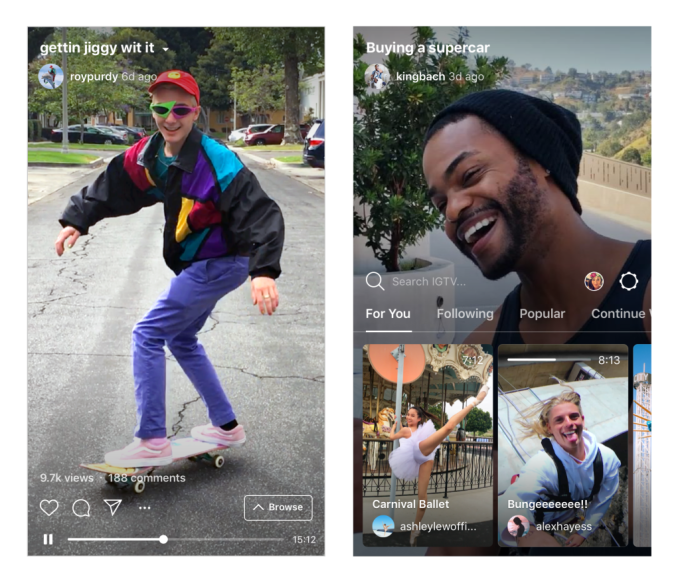

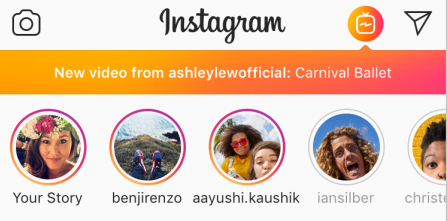

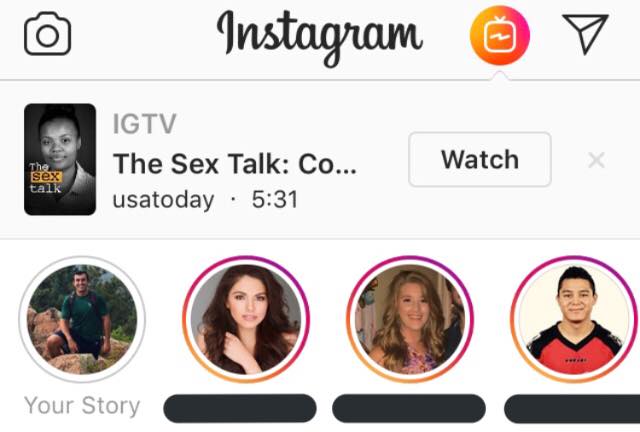

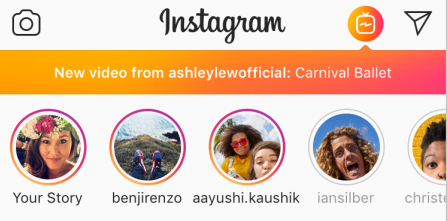

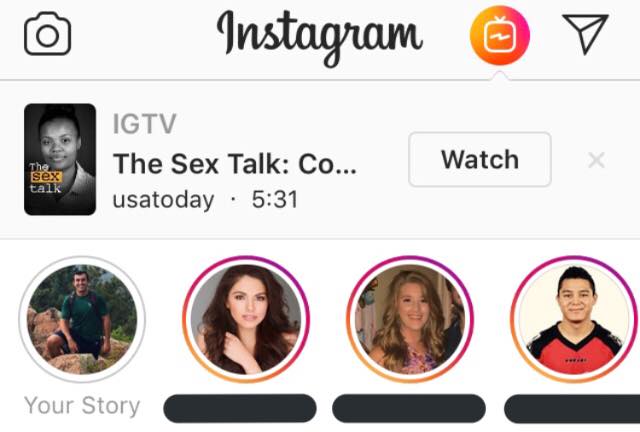

The one big surprise of the launch event was where IGTV would exist. Instagram announced it’d live in a standalone IGTV app, but also as a feature in the main app accessible from an orange button atop the home screen that would occasionally call out that new content was inside. But in essence, it was ignorable. IGTV didn’t get the benefit of being splayed out atop Instagram like Stories did. Blow past that one button and avoid downloading the separate app, and users could go right on tapping and scrolling through Instagram without coming across IGTV’s longer videos.

View counts of the launch partners reflect that. We looked at six launch partner creators, comparing their last six feed and IGTV videos older than a week and less than six months old, or fewer videos if that’s all they’d posted.

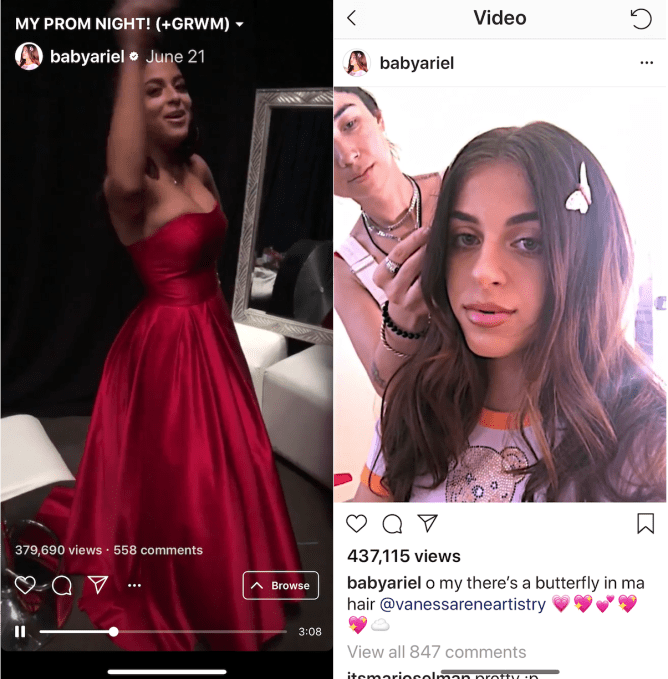

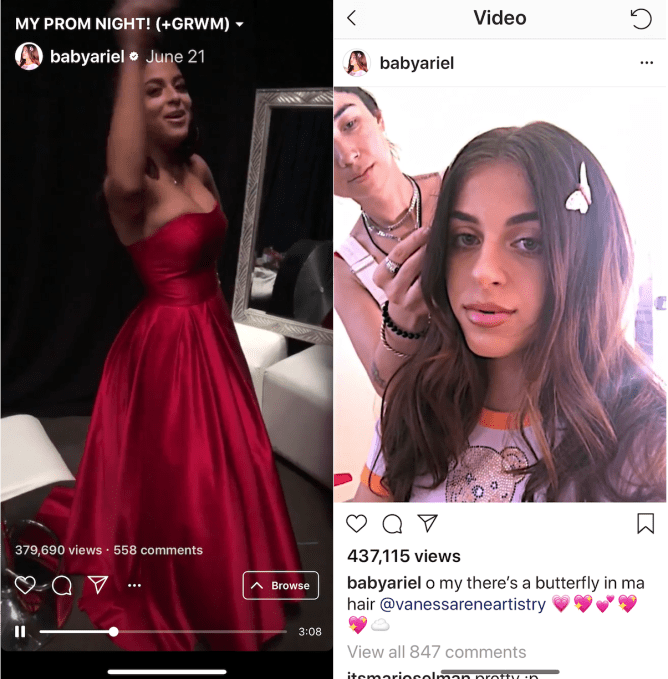

Only one of the six, BabyAriel, saw an obvious growth trend in her IGTV videos. Her candid IGTV monologues are performing the best of the six compared to feed. She’s earning an average of 243,000 views per IGTV video, about a third as many as she gets on her feed videos. “I’m really happy with my view counts because IGTV is just starting” BabyAriel tells me. She thinks the format will be good for behind-the-scenes clips that complement her longer YouTube videos and shorter Stories. “When I record anything, It’s vertical. When I turn my phone horizontal I think of an hour-long movie.”

Lele Pons, a Latin American comedy and music star who’s one of the most popular Instagram celebrities, gets about 5.7X more feed views than on her IGTV cooking show that averages 1.9 million hits. Instagram posted some IGTV highlights from the first month, but the most popular of now has 4.3 million views — less than half of what Pons gets on her average feed video.

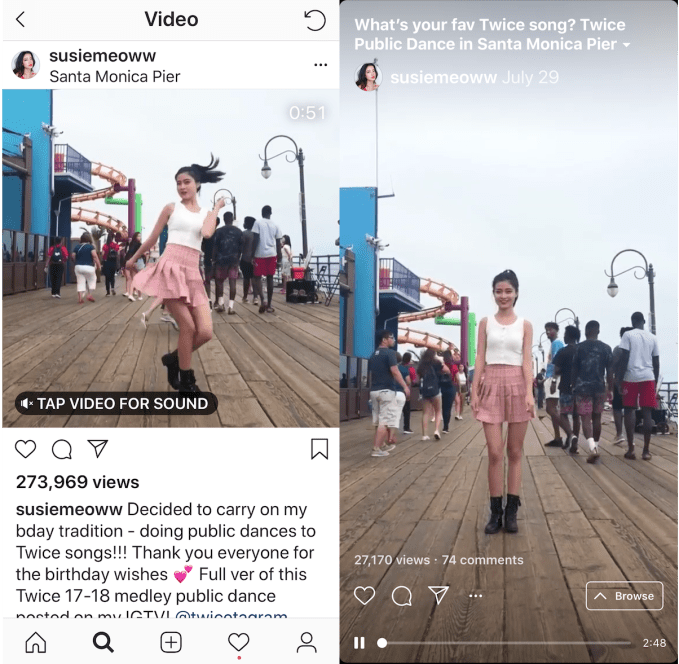

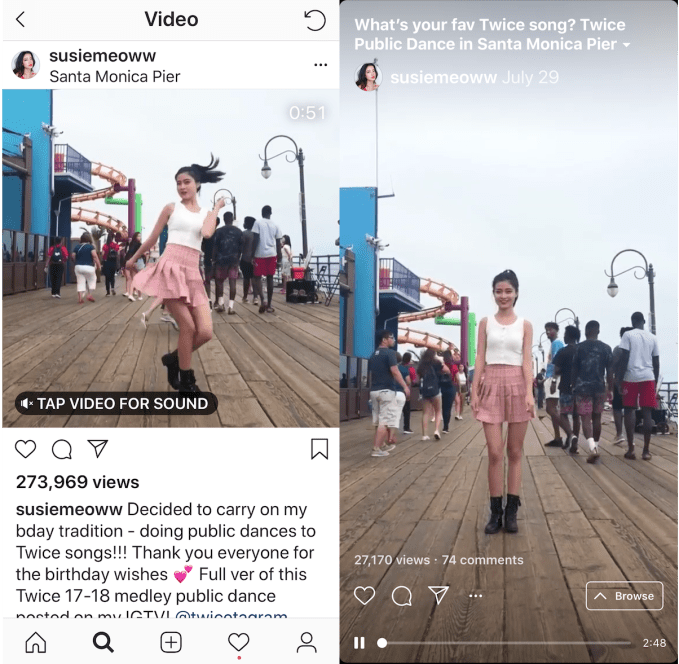

Fitness guides from Katie Austin averaged just 3,600 views on IGTV while she gets 7.5X more in the feed. Lauren Godwin’s colorful comedy fared 5.2X better in the feed. Bryce Xavier saw the biggest differential, earning 15.9X more views for his dance and culture videos. And in the most direct comparison, K-Pop dancer Susie Shu sometimes posts cuts from the same performance to the two destinations, like one that got 273,000 views in feed but just 27,000 on IGTV, with similar clips fairing an average of 7.8X better.

Again, this isn’t to say IGTV is a lame horse. It just isn’t roaring out of the gates. Systrom remains optimistic about inventing a new format. “The question is can we pull that off and the early signs are really good,” he tells me. “We’ve been pretty blown away by the reception and the usage upfront,” though he declined to share any specific statistics. Instagram promised to provide more insight into traction in the future.

YouTube star Casey Neistat is less bullish. He doesn’t think IGTV is working and that engagement has been weak. If IGTV views were surpassing those of YouTube, creators would flock to it, but so far view counts are uninspiring and not worth diverting creative attention, Neistat says. “YouTube offers the best sit-back consumption, and Stories offers active consumption. Where does IGTV fit in? I’m not sure” he tells me. “Why create all of this unique content if it gets lower views, it’s not monetizable, and the viewers aren’t there?”

Susie Shu averages 7.8X more video views in the Instagram feed than on IGTV

For now, the combination of an unfamiliar format, the absence of direction for how to use it and the relatively buried placement has likely tempered IGTV’s traction. Two months in, Instagram Stories was proving itself an existential threat to Snapchat — which it’s in fact become. IGTV doesn’t pose the same danger to YouTube yet, and it will need a strategy to support a more slow-burn trajectory.

The chicken and the IG problem

The first step to becoming a real YouTube challenger is to build up some tent-pole content that gives people a reason to open IGTV. Until there’s something that captures attention, any cross-promotion traffic Instagram sends it will be like pouring water into a bucket with a giant hole in the bottom. Yet until there’s enough viewers, it’s tough to persuade creators to shoot for IGTV since it won’t do a ton to boost their fan base.

Fortnite champion Ninja shares a photo of IGTV launch partners gathered backstage at the press event

Meanwhile, Instagram hasn’t committed to a monetization or revenue-sharing strategy for IGTV. Systrom said at the launch that “There’s no ads in IGTV today,” but noted it’s “obviously a very reasonable place [for ads] to end up.” Without enough views, though, ads won’t earn enough for a revenue split to incentivize creators. Perhaps Instagram will heavily integrate its in-app shopping features and sponsored content partnerships, but even those rely on having more traffic. Vine withered at Twitter in part from creators bailing due to its omission of native monetization options.

So how does IGTV solve the chicken-and-egg problem? It may need to swallow its pride and pay early adopters directly for content until it racks up enough views to offer sustainable revenue sharing. Instagram has never publicly copped to paying for content before, unlike its parent Facebook, which offered stipends ranging into the millions of dollars for publishers to shoot Live broadcasts and long-form Watch shows. Neither have led to a booming viewership, but perhaps that’s because Facebook has lost its edge with the teens who love video.

Instagram could do better if it paid the right creators to weather IGTV’s initial slim pickings. Settling on ad strategy creators can count on earning money from in the future might also get them to hang tight. Those deals could mimic the 55 percent split of mid-roll ad breaks Facebook gives creators on some videos. But again, the views must come first.

Alternatively, or additionally, it could double down on the launch strategy of luring creators with the potential to become the big fish in IGTV’s small-for-now pond. Backroom deals to trade being highlighted in its IGTV algorithm in exchange for high-quality content could win the hearts of these stars and their managers. Instagram would be wise to pair these incentives with vertical long-form video content creation workshops. It could bring its community, product and analytics leaders together with partnered stars to suss out what works best in the format and help them shoot it.

The cross-promo spigot

Once there’s something worth watching on IGTV, the company could open the cross-promo traffic spigot. At first, Instagram would send notifications about top content or IGTV posts from people you follow, and call them out with a little orange text banner atop its main app. Now it seems to understand it will need to be more coercive.

Last month, TechCrunch spotted Instagram showing promos for individual IGTV shows in the middle of the feed, hoping to redirect eyeballs there. And today, we found Instagram getting more aggressive by putting a bigger call out featuring a relevant IGTV clip with preview image above your Stories tray on the home screen. It may need to boost the frequency of these cross-promotions and stick them in-between Stories and Explore sections as well to give IGTV the limelight. These could expose users to creators they don’t follow already but might enjoy.

“It’s still early but I do think there’s a lot of potential when they figure out two things since the feature is so new,” says John Shahidi, who runs the Justin Bieber-backed Shots Studios, which produces and distributes content for Lele Pons, Rudy Mancuso and other Insta celebs. “1. Product. IGTV is not in your face so Instagram users aren’t changing behavior to consume. Timeline and Instagram Stories are in your face so those two are the most used features. 2. Discoverability. I want to see videos from people I don’t follow. Interesting stuff like cooking, product review, interesting content from brands but without following the accounts.” In the meantime, Shots Studios is launching a vertical-only channel on YouTube that Shahidi believes is the first of its kind.

Instagram will have to balance its strategic imperative to grow the long-form video hub and avoid spamming users until they hate the brand as a whole. Some think it’s already gone too far. “I think it’s super intrusive right now,” says Tiffany Zhong, once known as the world’s youngest venture capitalist who now runs Generation Z consulting firm Zebra Intelligence. “I personally find all the IGTV videos super boring and click out within seconds (and the only time I watch them are if I accidentally tapped on the icon when I tried to go to my DMs instead).” Desperately funneling traffic to the feature before there’s enough great content to power relevant recommendations for everyone could prematurely sour users on IGTV.

Systrom remains optimistic he can iterate his way to success. “What I want to see over the next six to 12 months is a consistent drumbeat of new features that both consumers and creators are asking for, and to look at the retention curve and say ‘are people continuing to watch? Are people continuing to upload?,'” says Systrom. “So far we are seeing that all of those are healthy. But again trying to judge a very new kind of audacious format that’s never really been done before in the first months is going to be really hard.”

Differentiator or deterrent?

The biggest question remains whether IGTV will remain devout to the orthodoxy of vertical-only. Loosening up to accept landscape videos too might nullify a differentiator, but also pipe in a flood of content it could then algorithmically curate to bootstrap IGTV’s library. Reducing the friction by allowing people to easily port content to or from elsewhere might make it feel like less of a gamble for creators deciding where to put their production resources. Instagram itself expanded from square-only to portrait and landscape photos in the feed in 2015.

“My advice would be to make the videos horizontal. We’ve all come to understand vertical as ‘short form’ and horizontal as ‘long form,'” says Sayman. “It’s in the act of rotating your phone to landscape that you indicate to yourself and to your mobile device that you will not be context switching for the next few minutes, but rather intend to focus on one piece of content for an extended period of time.” This would at least give users more to watch, even if they ended up viewing landscape videos with their phones in portrait orientation.

“My advice would be to make the videos horizontal. We’ve all come to understand vertical as ‘short form’ and horizontal as ‘long form,'” says Sayman. “It’s in the act of rotating your phone to landscape that you indicate to yourself and to your mobile device that you will not be context switching for the next few minutes, but rather intend to focus on one piece of content for an extended period of time.” This would at least give users more to watch, even if they ended up viewing landscape videos with their phones in portrait orientation.

This might be best as a last-ditch effort if it can’t get enough content flowing in through other means. But at least Instagram should offer a cropping tool that lets users manually select what vertical slice of a landscape video they want to show as they watch, rather than just grabbing the center or picking one area on the side for the whole clip. This could let creators repurpose landscape videos without things getting awkwardly half cut out of frame.

Former Facebook employee and social investor Josh Elman, who now works at Robinhood, told me he’s confident the company will experiment as much as necessary. “I think Facebook is relentless. They know that a ton of consumers watch video online. And most discover videos through influencers or their friends. (Or Netflix). Even though Watch and IGTV haven’t taken the world by storm yet, I bet Facebook won’t stop until they find the right mix.”

There’s a goldmine waiting if it does. Unlike on Facebook, there’s no Regram feature, you can’t post links, and outside of Explore you just see who you already follow on Instagram. That’s made it great at delivering friendly video and clips from your favorite stars, but leaves a gaping hole where serendipitous viewing could be. IGTV fills that gap. The hours people spend on Facebook watching random videos and their accompanying commercials have lifted the company to over $13 billion in revenue per quarter. Giving a younger audience a bottomless pit of full-screen video could produce the same behavior and profits on Instagram without polluting the feed, which can remain the purest manifestation of visual feed culture. But that’s only if IGTV can get enough content uploaded.

Puffed up by the success of besting its foe Snapchat, Instagram assumed it could take the long-form video world by storm. But the grand entrance at its debutante ball didn’t draw enough attention. Now it needs to take a different tack. Tone down the cross-promo for the moment. Concentrate on teaching creators how to find what works on the format and incentivizing them with cash and traffic. Develop some must-see IGTV and stoke a viral blockbuster. Prove the gravity of extended, personality-driven vertical video. Only then should it redirect traffic there from the feed, Stories, and Explore.

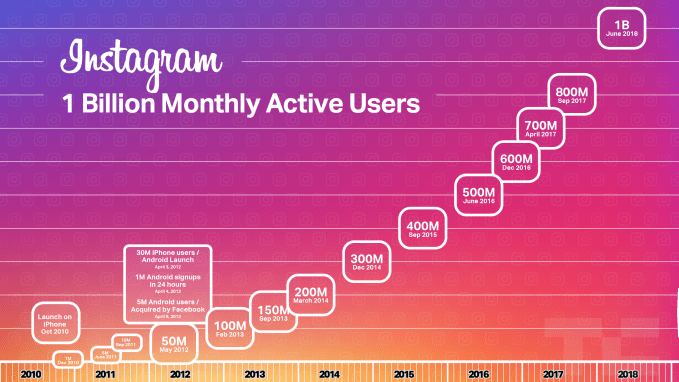

YouTube’s library wasn’t built overnight, and neither will IGTV’s. Facebook’s deep pockets and the success of Instagram’s other features give it the runway necessary to let IGTV take off. With 1 billion monthly users, and 400 million daily Stories users gathered in just two years, there are plenty of eyeballs waiting to be seduced. Systrom concludes, “Everything that is great starts small.” IGTV’s destiny will depend on Instagram’s patience.

In

In

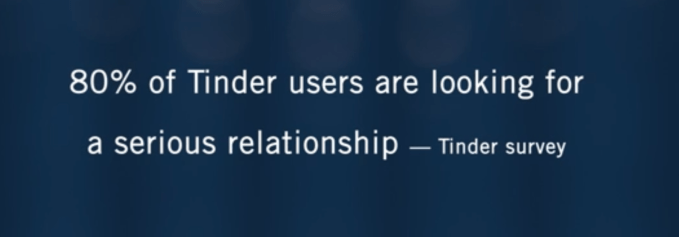

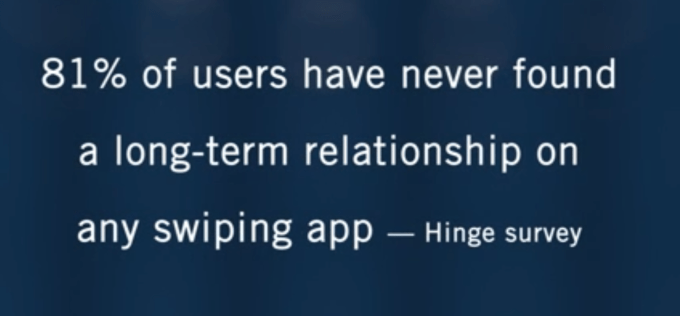

The sending of dick pics; men posing with fish in their profile photos; that supposedly happy couple “looking for a third” (spoiler alert: they’re not happy and are broken up by end of film); the “DTF?” come-ons; and basically every other reason people delete these apps in the first place.

The sending of dick pics; men posing with fish in their profile photos; that supposedly happy couple “looking for a third” (spoiler alert: they’re not happy and are broken up by end of film); the “DTF?” come-ons; and basically every other reason people delete these apps in the first place.

“

“