It’s never a good sign when, in order to discuss the near future of technology, you first have to talk about epidemiology–but I’m afraid that’s where we’re at. A week ago I wrote “A pandemic is coming.” I am sorry to report, in case you hadn’t heard, events since have not exactly proved me wrong.

The best current estimates are that, absent draconian measures like China’s, the virus will infect 40-70% of the world’s adults over the next year or so. (To be extra clear, though, a very sizable majority of cases will be mild or asymptomatic.)

This obviously leads to many questions. The most important is not “can we stop it from spreading?” The answer to that is already, clearly, no. The most important is “will its spread be fast or slow?” The difference is hugely important. To re-up this tweet/graph from last week:

A curve which looks like a dramatic spike risks overloading health care systems, and making everything much worse, even though only a small percentage of the infected will need medical care. Fortunately, it seems likely (to me, at least) that nations with good health systems, strong social cohesion, and competent leadership will be able to push the curve down into a manageable “hill” distribution instead.

Unfortunately, if (like me) you happen to live in the richest country in the world, none of those three conditions apply. But let’s optimistically assume America’s sheer wealth helps it dodge the bad-case scenarios. What then?

Then we’re looking at a period measured in months during which the global supply chain is sputtering, and a significant fraction of the population is self-isolating. The former is already happening:

It’s hard to imagine us avoiding a recession in the face of simultaneous supply and demand shocks. (Furthermore, if the stock markets keep dropping a couple percent every time there’s another report of spreading Covid-19, we’ll be at Dow 300 and FTSE 75 in a month or two–I expect a steady, daily drip-feed of such news for some time. Presumably traders will eventually figure that out.) So what happens to technology, and the tech industry, then?

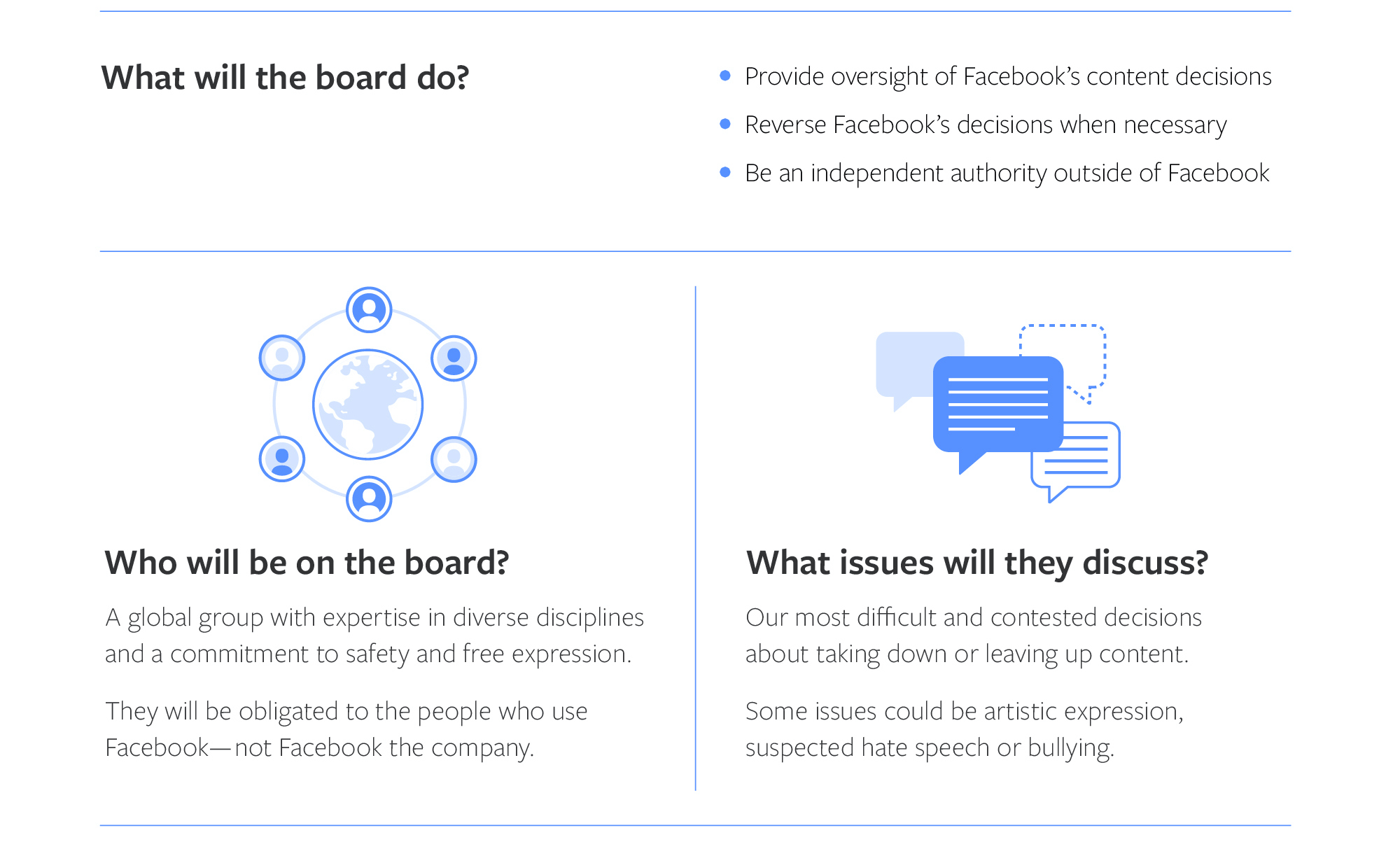

Some obvious conclusions: technology which aids and enables remote work / collaboration will see growth. Biotech and health tech will receive new attention. More generally, though, might this accelerate the pace of technological change around the world?

A little over a year ago I wrote a piece entitled “Here comes the downturn” (predicting “Late 2019 or early 2020, says the smart money.”) To quote, er, myself:

The theory goes: every industry is becoming a technology industry, and downturns only accelerate the process. It’s plausible. It’s uncomfortable, given how much real human suffering and dismay is implicit in the economic disruption from which we often benefit. And on the macro scale, in the long run, it’s even probably true. Every downturn is a meteor that hits the dinosaurs hardest, while we software-powered mammals escape the brunt.

Even if so, though, what’s good for the industry as a whole is going to be bad for a whole lot of individual companies. Enterprises will tighten their belts, and experimental initiatives with potential long-term value but no immediate bottom-line benefit will be among the first on the chopping block. Consumers will guard their wallets more carefully, and will be ever less likely to pay for your app and/or click on your ad. And everyone will deleverage and/or hoard their cash reserves like dragons, just in case.

None of that seems significantly less true of a recession caused by a physical shock rather than a mere economic one. My guess is it will be relatively short and sharp, and this time next year both pandemic and recession will essentially be behind us. In the interim, though, it seems very much as if we’re looking at one of the most disconcertingly interesting years in a very long time. Let’s hope it doesn’t get too much moreso.