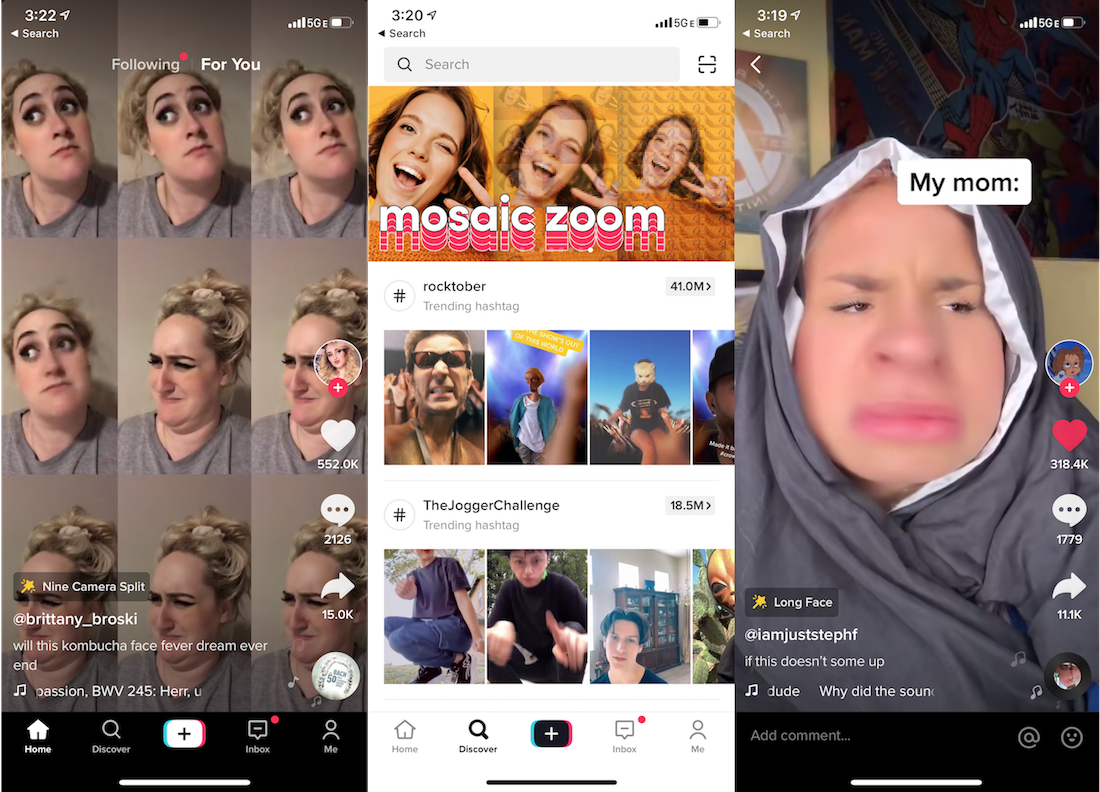

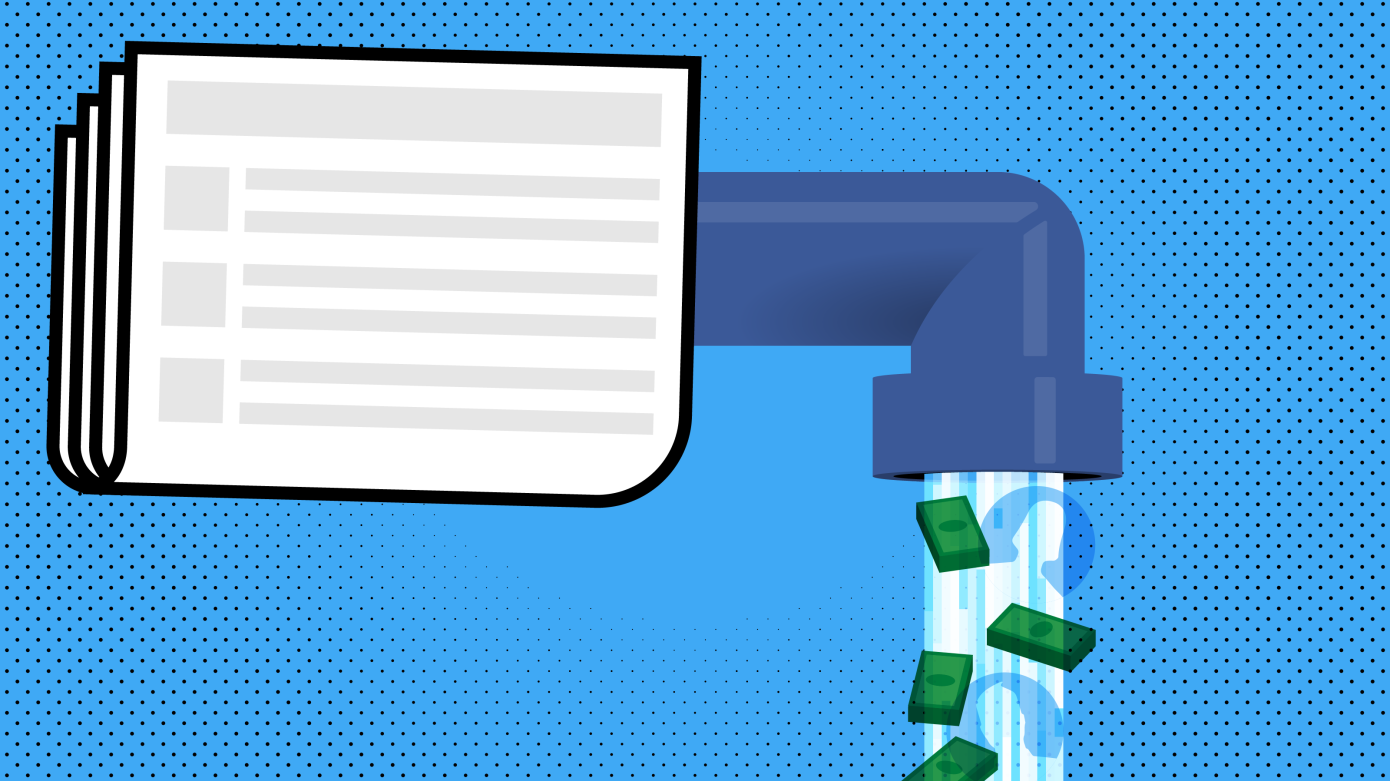

Are we really doing this again? After the pivot to video. After Instant Articles. After news was deleted from the News Feed. Once more, Facebook dangles extra traffic, and journalism outlets leap through its hoop and into its cage.

Tomorrow, Facebook will unveil its News tab. About 200 publishers are already aboard including the Wall Street Journal and BuzzFeed News, and some will be paid. None seem to have learned the lesson of platform risk.

When you build on someone else’s land, don’t be surprised when you’re bulldozed. And really, given Facebook’s flawless track record of pulling the rug out from under publishers, no one should be surprised.

I could just re-run my 2015 piece on how “Facebook is turning publishers into ghost writers,” merely dumb content in its smart pipe. Or my 2018 piece on “how Facebook stole the news business” by retraining readers to abandon publishers’ sites and rely on its algorithmic feed.

Chronicling Facebook’s abuse of publishers

Let’s take a stroll back through time and check out Facebook’s past flip-flops on news that hurt everyone else:

-In 2007 before Facebook even got into news, it launches a developer platform with tons of free virality, leading to the build-up of companies like Zynga. Once that spam started drowning the News Feed, Facebook cut it and Zynga off, then largely abandoned gaming for half a decade as the company went mobile. Zynga never fully recovered.

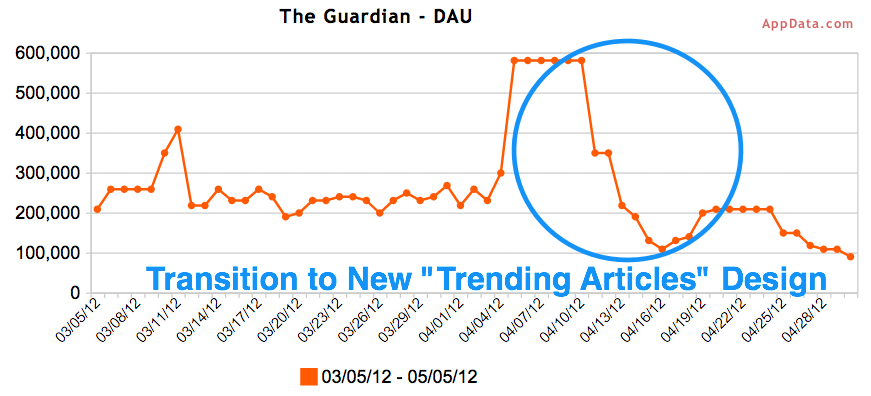

-In 2011, Facebook launches the open graph platform with Social Reader apps that auto-share to friends what news articles you’re reading. Publishers like The Guardian and Washington Post race to build these apps and score viral traffic. But in 2012, Facebook changes the feed post design and prominence of social reader apps, they lost most of their users, those and other outlets shut down their apps, and Facebook largely abandons the platform

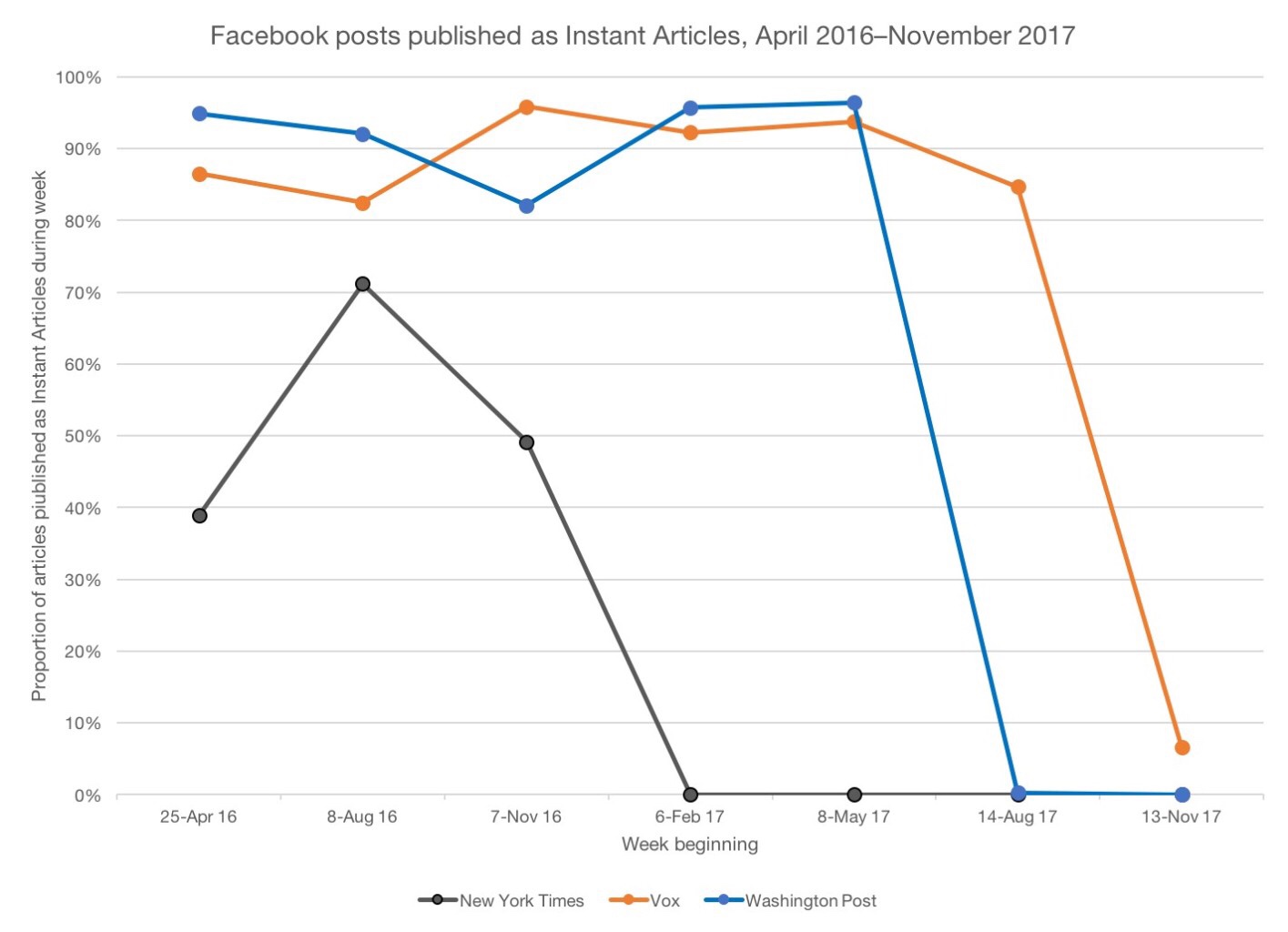

-In 2015, Facebook launches Instant Articles, hosting news content inside its app to make it load faster. But heavy-handed rules restricting advertising, subscription signup boxes, and recirculation modules lead publishers to get little out of Instant Articles. By late 2017, many publishers had largely abandoned the feature.

Decline of Instant Article use, via Columbia Journalism Review

-Also in 2015, Facebook started discussing “the shift to video,” citing 1 billion video views per day. As the News Feed algorithm prioritized video and daily views climbed to 8 billion within the year, newsrooms shifted headcount and resources from text to video. But a lawsuit later revealed Facebook already knew it was inflating view metrics by 150% to 900%. By the end of 2017 it had downranked viral videos, eliminated 50 million hours per day of viewing (over 2 minutes per user), and later pulled back on paying publishers for Live video as it largely abandoned publisher videos in favor of friend content.

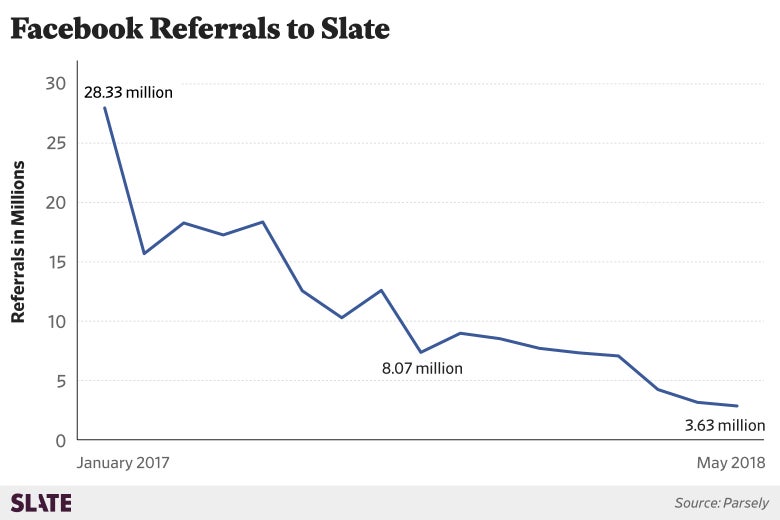

-In 2018, Facebook announced it would decrease the presence of news in the News Feed from 5% to 4% while prioritizing friends and family content. Referral shrank sharply, with Google overtaking it as the top referrer, while some outlets were hit hard like Slate which lost 87% of traffic from Facebook. You’d understand if some publishers felt…largely abandoned.

Facebook referral traffic to slate plummeted 87% after a strategy change prioritized friends and family content over news

Are you sensing a trend?

Facebook typically defends the whiplash caused by its strategic about-faces by claiming it does what’s best for users, follows data on what they want, and tries to protect them. What it leaves out is how the rest of the stakeholders are prioritized.

Aggregated to death

I used to think of Facebook as being in a bizarre love quadrangle with its users, developers and advertisers. But increasingly it feels like the company is in an abusive love/hate relationship with users, catering to their attention while exploiting their privacy. Meanwhile, it dominates the advertisers thanks to its duopoly with Google that lets it survive metrics errors, and the developers as it alters their access and reach depending on if it needs their users or is backpedaling after a data fiasco.

Only recently after severe backlash does society seem to be getting any of Facebook’s affection. And perhaps even lower in the hierarchy would be news publishers. They’re not a huge chunk of Facebook’s content or, therefore, its revenue, they’re not part of the friends and family graph at the foundation of the social network, and given how hard the press goes on Facebook relative to Apple and Google, it’s hard to see that relationship getting much worse than it already is.

That’s not to say Facebook doesn’t philosophically care about news. It invests in its Journalism Project hand-outs, literacy and its local news feature Today In. Facebook has worked diligently in the wake of Instant Article backlash to help publishers build out paywalls. Given how centrally it’s featured, Facebook’s team surely reads plenty of it. And supporting the sector could win it some kudos between scandals.

But what’s not central to Facebook’s survival will never be central to its strategy. News is not going to pay the bills, and it probably won’t cause a major change in its hallowed growth rate. Remember that Twitter, which hinges much more on news, is 1/23rd of Facebook’s market cap.

So hopefully at this point we’ve established that Facebook is not an ally of news publishers.

At best it’s a fickle fair-weather friend. And even paying out millions of dollars, which can sound like a lot in journalism land, is a tiny fraction of the $22 billion in profit it earned in 2018.

Whatever Facebook offers publishers is conditional. It’s unlikely to pay subsidies forever if the News tab doesn’t become sustainable. For newsrooms, changing game plans or reallocating resources means putting faith in Facebook it hasn’t earned.

What should publishers do? Constantly double-down on the concept of owned audience.

They should court direct traffic to their sites where they have the flexibility to point users to subscriptions or newsletters or podcasts or original reporting that’s satisfying even if it’s not as sexy in a feed.

Meet users where they are, but pull them back to where you live. Build an app users download or get them to bookmark the publisher across their devices. Develop alternative revenue sources to traffic-focused ads, such as subscriptions, events, merchandise, data and research. Pay to retain and recruit top talent with differentiated voices.

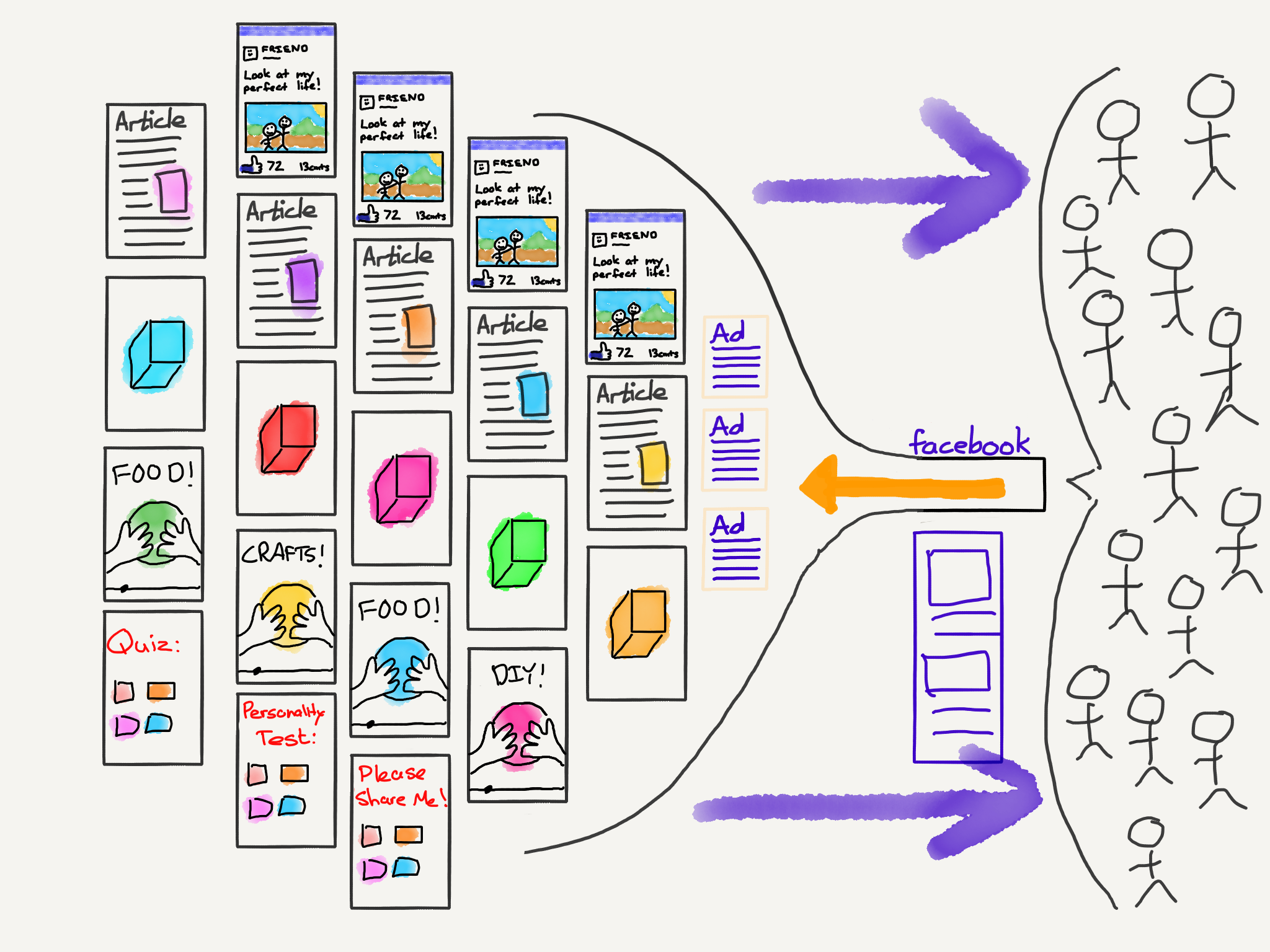

What scoops, opinions, analysis, and media can’t be ripped off or reblogged? Make that. What will stand out when stories from every outlet are stacked atop each other? Because apparently that’s the future. Don’t become generic dumb content fed through someone else’s smart pipe.

As Ben Thompson of Stratechery has proselytized, Facebook is the aggregator to which the spoils of attention and advertisers accrue as they’re sucked out of the aggregated content suppliers. To the aggregator, the suppliers are interchangeable and disposable. Publishers are essentially ghostwriters for the Facebook News destination. Becoming dependent upon the aggregator means forfeiting control of your destiny.

Surely, experimenting to become the breakout star of the News tab could pay dividends. Publishers can take what it offers if that doesn’t require uprooting their process. But with everything subject to Facebook’s shifting attitudes, it will be like publishers trying to play bocce during an earthquake.

[Featured Image: Russell Werges]