You wake up, and check your phone, and see a new condemnation. Some awful person has said something outrageously insulting. Something actually evil, if you think about it. Something that belittles, dehumanizes, and/or argues against the freedom and agency of a whole category of people.

You add your voice to the furious chorus in response. How can you not? These people may never understand how wrong they are, they’re too ignorant and wedded to their idiocy for that, but they need to know that they are opposed, and their opponents are legion.

We all know what you mean when you say ‘these people.’ The ones who voted for those awful faces on every news site and TV channel, the ones whose names alone cause you to clench with fury. The ones responsible for the awful, unforgivable things happening at the border. The ones responsible for the reports of violence in the streets.

If pushed you’d probably admit that only some of These People are genuinely evil. More than you could have imagined in your worst nightmares five years ago, but still, only some. Others may be prisoners of their upbringing, or their ignorance, or victims of their own hardships, lashing out wildly. But what they all seem to have in common is an incapacity for compassion.

It’s easy to distance yourself from Them. It’s hard not to. The overwhelming majority of the people with whom you actually interact are Us.

You know you should try to feel compassion for Them, as you should for everyone. Not sympathy. Sympathy is very different. But your religion, or your spirituality, or your morality, or simply your belief, teaches you compassion for all. But how can you hold compassion for people who seem incapable of compassion themselves? People who don’t condemn, who actually cheer, what’s happening at the border?

And so every online outrage leaches a little more compassion away, widens and deepens the abyss between Us and Them a little further. You know intellectually that many of these viral outrages stem from bots, programmed by trolls or worse, and each new one does not represent every member of … them.

But you can’t help but grow more certain with each new outrage, in your heart if not your head, that there is a Them. That there are no longer people with whom one can reasonably disagree. That there are now only Us, and Them.

You realize when you think about it that this makes it easier to give people who are notionally Us a pass when they too behave with a flagrant lack of compassion, or judge people’s whole lives by their worst moments, or prioritize the purity of the process they have decreed over any actual results accomplished.

You realize that the growing abyss between Us and Them makes both sides close ranks, makes it harder for people who are Them and yet who have uneasy, even horrified feelings about what’s happening at the border in their name, to at least speak against it. They should anyway. Of course they should. But people are weak. The easier something becomes, the more that people do it.

You understand, on some level, that the online divide is different from the awful things actually happening offline. That the latter matters, deeply, and the former … not so much. That the former distracts both sides from great systemic injustices which have learned to lie hidden in bland terminology, coolly steering clear of the outrage of Us versus Them.

But you slept poorly, you’re exhausted, and you already have so much to do, so many duties to attend to at your frustrating job, so many worries to keep at bay, once you get out of this bed. Maybe all that is because of those systemic injustices, but those are a rot, those are cancer, those are bone-deep, and the evils at the border are an open wound about which something must done immediately. They are responsible for those evils. They must be fought and stopped.

So you add your voice to the furious chorus. And you give more money to those fighting the real fight at the border, because you know that’s what’s actually important. And maybe before you roll out of bed you pause to wonder how much the great online divide represents reality, or how much it prefigures reality; whether They really have all lost their minds and their moral compasses.

And you can’t help but wonder: even if they haven’t, what can now be done?

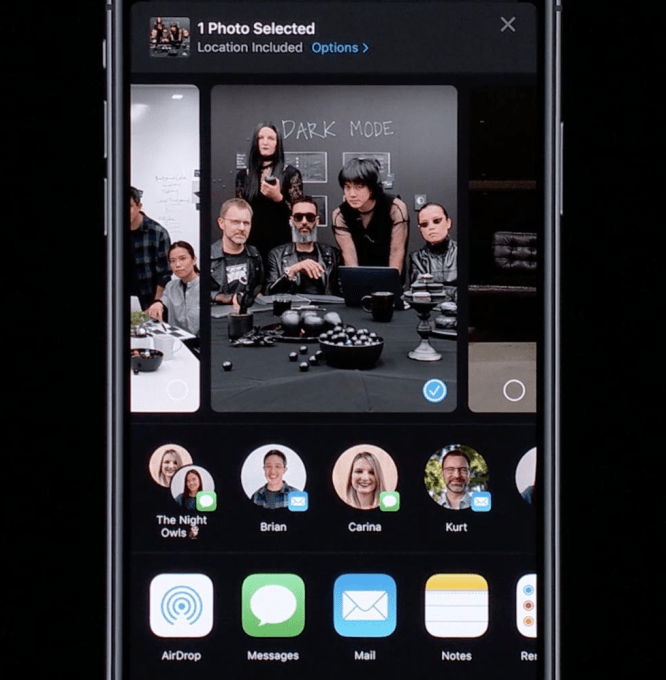

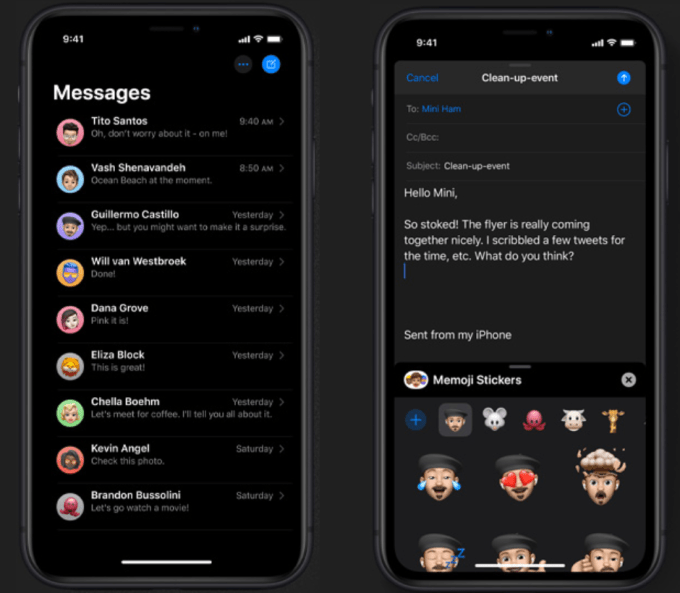

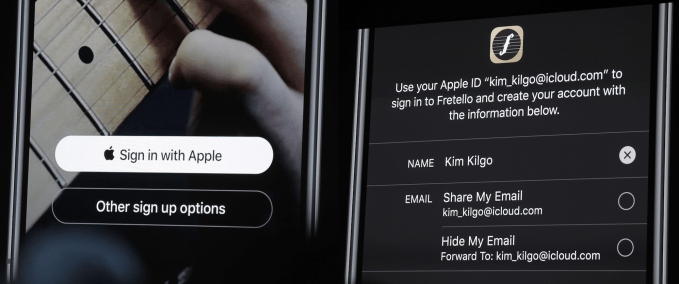

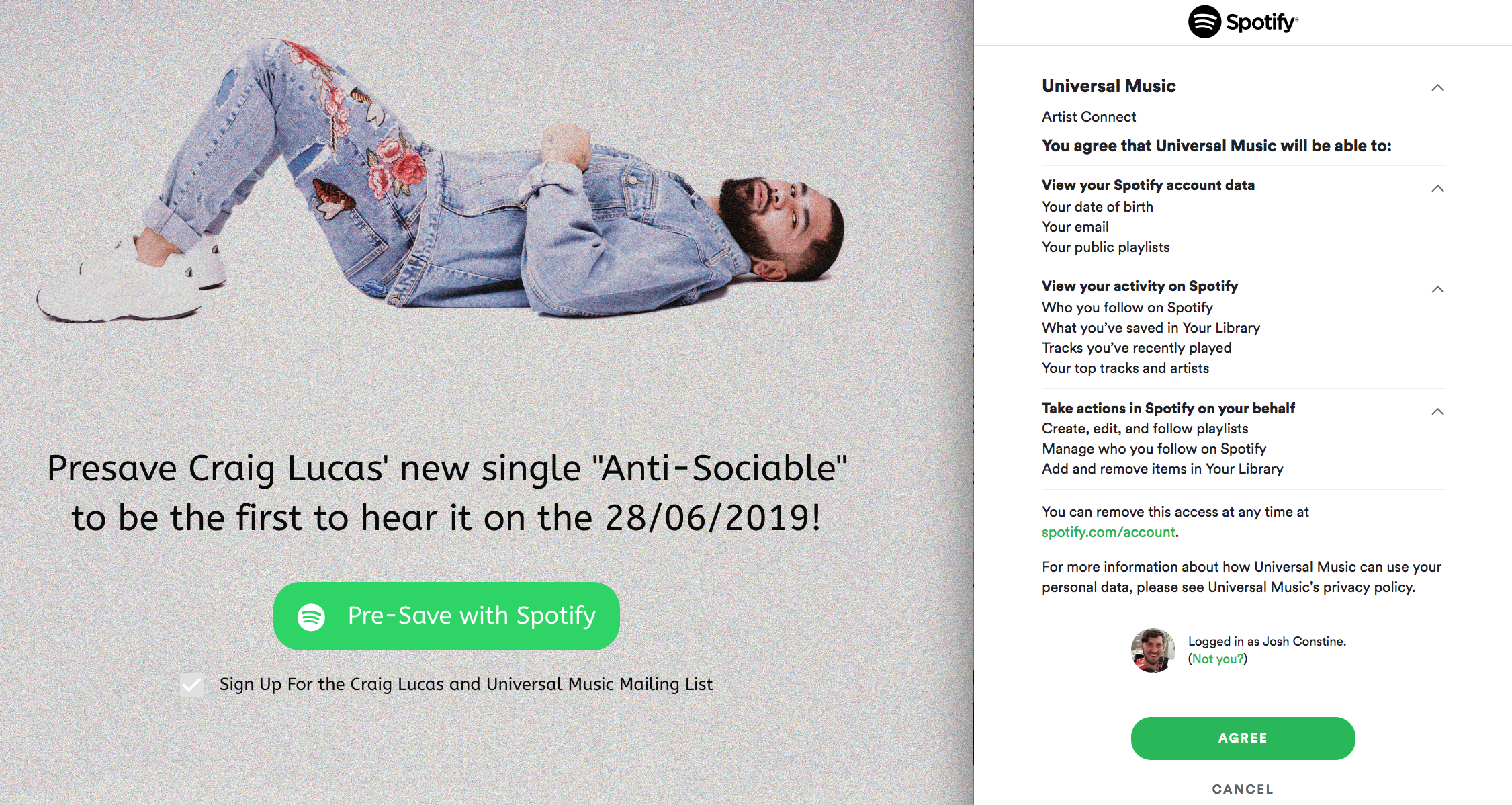

The problem is that this philosophy is hard to monetize for a social network that needs to maximize broadcasted content and engagement to score ad views. But it’s easy to monetize if you sell the phone and then let people be as private as they want on it. That’s why today at

The problem is that this philosophy is hard to monetize for a social network that needs to maximize broadcasted content and engagement to score ad views. But it’s easy to monetize if you sell the phone and then let people be as private as they want on it. That’s why today at