Wasting time every night debating with yourself or your partner about what to watch on Netflix is a drag. It burns people’s time and good will, robs great creators of attention, and leaves Netflix vulnerable to competitors who can solve discovery. Netflix itself says the average user spends 18 minutes per day deciding.

To date, Netflix’s solution has been its state-of-the-art artificial intelligence that offers personalized recommendations. But that algorithm is ignorant of how we’re feeling in the moment, what we’ve already seen elsewhere, and if we’re factoring in what someone else with us wants to watch too.

Netflix is considering a Shuffle button. [Image Credit: AndroidPolice]

Here are three much more exciting, applicable, and lucrative ways for Netflix (or Hulu, Amazon Prime Video, or any of the major streaming services) to get us to stop browsing and start chilling:

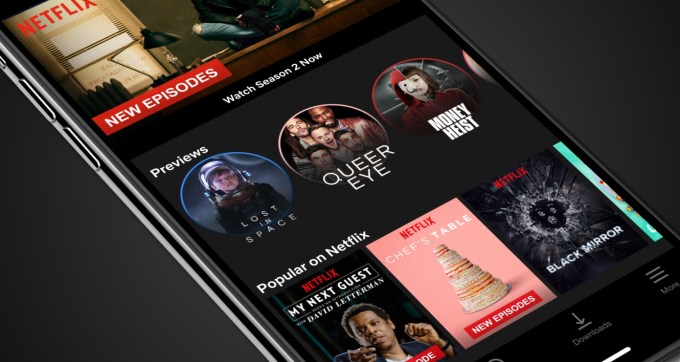

Netflix Channels

For the history of broadcast television, people surfed their way to what to watch. They turned on the tube, flipped through a few favorite channels, and jumped in even if a show or movie had already started. They didn’t have to decide between infinite options, and they didn’t have to commit to starting from the beginning. We all have that guilty pleasure we’ll watch until the end whenever we stumble upon it.

Netflix could harness that laziness and repurpose the concept of channels so you could surf its on-demand catalog the same way. Imagine if Netflix created channels dedicated to cartoons, action, comedy, or history. It could curate non-stop streams of cherry-picked content, mixing classic episodes and films, new releases related to current events, thematically relevant seasonal video, and Netflix’s own Original titles it wants to promote.

For example, the comedy channel could run modern classic films like 40-Year Old Virgin and Van Wilder during the day, top episodes of Arrested Development and Parks And Recreation in the afternoon, a featured recent release film like The Lobster in primetime, and then off-kilter cult hits like Monty Python or its own show Big Mouth in the late night slots. Users who finish one video could get turned on to the next, and those who might not start a personal favorite film from the beginning might happily jump in at the climax.

Short-Film Bundles

There’s a rapidly expanding demographic of post-couple pre-children people desperately seeking after-work entertainment. They’re too old or settled to go out every night, but aren’t so busy with kids that they lack downtime.

But one big shortcoming of Netflix is that it can be tough to get a satisfying dose of entertainment in a limited amount of time before you have to go to bed. A 30-minute TV show is too short. A lot of TV nowadays is serialized so it’s incomprehensible or too cliffhanger-y to watch a single episode, but sometimes you can’t stay up to binge. And movies are too long so you end up exhausted if you manage to finish in one sitting.

Netflix could fill this gap by bundling three or so short films together into thematic collections that are approximately 45 minutes to an hour in total.

Netflix could commission Originals and mix them with the plethora of untapped existing shorts that have never had a mainstream distribution channel. They’re often too long or prestigious to live on the web, but too short for TV, and it’s annoying to have to go hunting for a new one every 15 minutes. The whole point here is to reduce browsing. Netflix could create collections related to different seasons, holidays, or world news moments, and rebundle the separate shorts on the fly to fit viewership trends or try different curational angles.

Often artful and conclusive, they’d provide a sense of culture and closure that a TV episode doesn’t. If you get sleepy you could save the last short, and there’s a feeling of low commitment since you could skip any short that doesn’t grab you.

The Nightly Water Cooler Pick

One thing we’ve lost with the rise of on-demand video are some of those zeitgeist moments where everyone watches the same thing the same night and can then talk about it together the next day. We still get that with live sports, the occasional tent pole premier like Game Of Thrones, or when a series drops for binge-watching like Stranger Things. But Netflix has the ubiquity to manufacture those moments that stimulate conversation and a sense of unity.

Netflix could choose one piece of programming per night per region, perhaps a movie, short arc of TV episodes, or one of the short film bundles I suggested above and stick it prominently on the home page. This Netflix Zeitgeist choice would help override people’s picky preferences that get them stuck browsing by applying peer pressure like, “well, this is what everyone else will be watching.”

Netflix’s curators could pick content matched with an upcoming holiday like a Passover TV episode, show a film that’s reboot is about to debut like Dune or Clueless, pick a classic from an actor that’s just passed away like Luke Perry in the original Buffy movie, or show something tied to a big event like Netflix is currently doing with Beyonce’s Coachella concert film. Netflix could even let brands and or content studios pay to have their content promoted in the Zeitgeist slot.

As streaming service competition heats up and all the apps battle for the best back catalog, it’s not just exclusives but curation and discovery that will set them apart. These ideas could make Netflix the streaming app where you can just turn it on to find something great, be exposed to gorgeous shorts you’d have never known about, or get to participate in a shared societal experience. Entertainment shouldn’t have to be a chore.

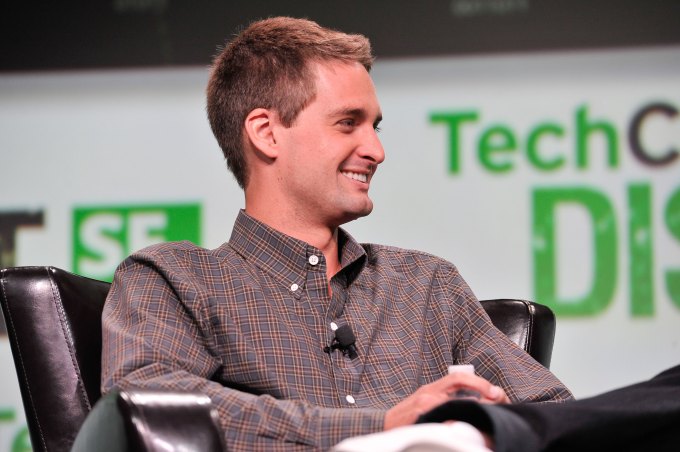

Again, the biggest barrier to this path is Spiegel. Combine totalitarian voting control with the

Again, the biggest barrier to this path is Spiegel. Combine totalitarian voting control with the  Increasingly, Apple must rely on its iOS software to compete for customers with Android headsets. But you know who’s great at making interesting software? Snapchat. You know who has a great relationship with the next generation of phone owners? Snapchat. And do you know whose CEO could probably smile earnestly beside Tim Cook announcing a brighter future for social media unlocked by two privacy-focused companies joining forces? Snapchat. Plus, think of all the fun Snapple jokes?

Increasingly, Apple must rely on its iOS software to compete for customers with Android headsets. But you know who’s great at making interesting software? Snapchat. You know who has a great relationship with the next generation of phone owners? Snapchat. And do you know whose CEO could probably smile earnestly beside Tim Cook announcing a brighter future for social media unlocked by two privacy-focused companies joining forces? Snapchat. Plus, think of all the fun Snapple jokes?